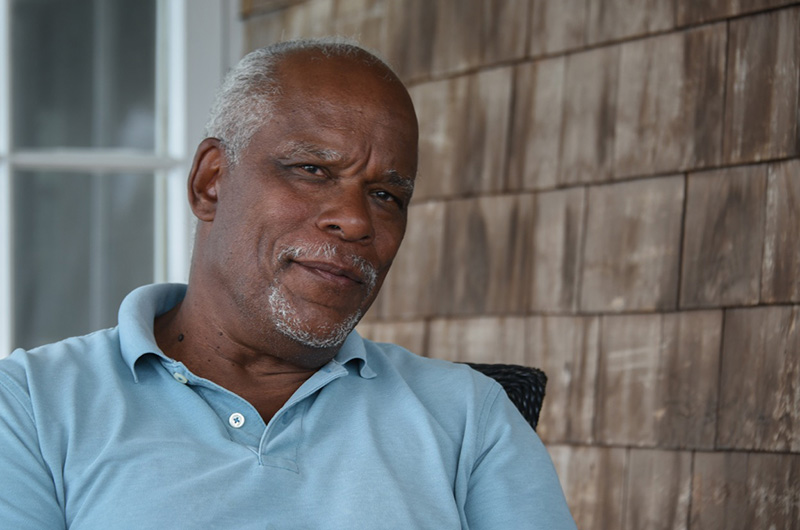

When documentary filmmaker and seasonal Vineyard resident Stanley Nelson began work on his latest film about the history of the crack epidemic he did so with one clear intention — to set the record straight.

“It’s clear that part of how we got here was kind of this big lie that these are monsters, they’re super predators, all those things that really aren’t true,” said Mr. Nelson. “I thought that nobody had really taken a look back, given some historical time.”

The documentary Crack: Cocaine, Corruption and Conspiracy is a tightly packed look back at the epidemic that ravaged communities of color across the United States. The film also connects the dots to today, illuminating the foundations of mass incarceration and mandatory sentencing through the war on drugs campaign.

The film was released by Netflix on Jan. 11 after a lengthy editing process that Mr. Nelson concluded from his home in Oak Bluffs. In a phone interview with the Gazette this week, Mr. Nelson reflected on the film, the era and the stories that led him to the project.

“Living in New York city, I was, like so many people, really affected by that time,” said Mr. Nelson. “So many people I grew up with got caught up in the crack world, lives were changed and sometimes devastated by it, and in a way it’s been kind of largely forgotten.”

A veteran documentarian, Mr. Nelson has made films on topics ranging from features on Miles Davis and the Black Panthers to a personal story about his family’s connection to Oak Bluffs. Mr. Nelson has earned multiple Emmy and Peabody awards and received the National Medal in the Humanities from President Obama in 2013.

He feels his latest film marks a shift.

“It’s different. It was, you know, a chance to do something that was a little more contemporary.”

Spanning from 1980 to the mid-1990’s, the film traces the story of crack from the early days of the Reagan administration to its consequences over a decade later, drawing connections between the stories of individuals and the broader political movements of the time. The film takes aim at the historical record, pushing back at much of the archival material it presents.

“We knew that there was a lot of footage, public service announcements and TV shows about crack and the war on drugs that we remembered, but reporting tended to kind of be over the top and sometimes just outright untrue,” recalled Mr. Nelson.

Presidential addresses, media coverage and discredited theories about the impact of the drug on babies are among the sources the film challenges. At many points, Mr. Nelson also draws comparisons between public response to the crack epidemic and contemporary conversations about the opioid crisis.

“You can’t think about crack without thinking about how different the opioid crisis is talked about today, but we didn’t want to constantly flash forward to the opioid crisis,” said Mr. Nelson. “I think one of the great things about being a filmmaker is when the audience feels like they connect the dots themselves.”

All this, Mr. Nelson said, is set to a soundtrack of early hip-hop hits by artists like Nas and Run DMC, giving the film its sense of time and place.

“Crack hit at the same time as hip-hop really came into public consciousness. What hip hop was doing was talking directly about what was happening on the streets in a way that the popular music didn’t before.”

Work on the film started over two years ago, when Mr. Nelson began scouring archives, nonfiction books and news clipping for information.

“It’s kind of like detective work, you just kind of keep following every lead,” he said of his creative process.

The film’s narrative arc, though mapped out at the beginning, changed many times during process, Mr. Nelson said. He cited vivid interviews with former drug dealers and users, journalists and government officials as leading factors. Their voices brought history to life, he said.

“Things constantly changed. Part of the story of crack is the layers. On one level, it’s the story of the streets, then on another level it’s the story of the police and the state, and then the story of the federal government and the Iran-Contra affair. That made the story, I think, really interesting because it didn’t just exist on any one level.”

Though the time period of the documentary concludes around the turn of the century, the legacy of the crack era is still very much at play today, Mr. Nelson said.

“I think it’s really important to think about how we got here,” he said. “Crack in many ways led to the war on drugs, which led to over policing and the kind of policing that we saw this summer with the murder of George Floyd, and the Black Lives Matter marches…It has a direct line to where we are today.”

Reflecting on the current political climate, Mr. Nelson was adamant that the film was not made as a piece of social activism. Instead, he hopes the documentary will serve as a model for the future.

“In some ways, the film is a cautionary tale — don’t make the same mistake twice that we made. With crack, it’s too late to go back. But we can look at the crises that we’re into now and really try to find solutions that are actually solutions.”

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »