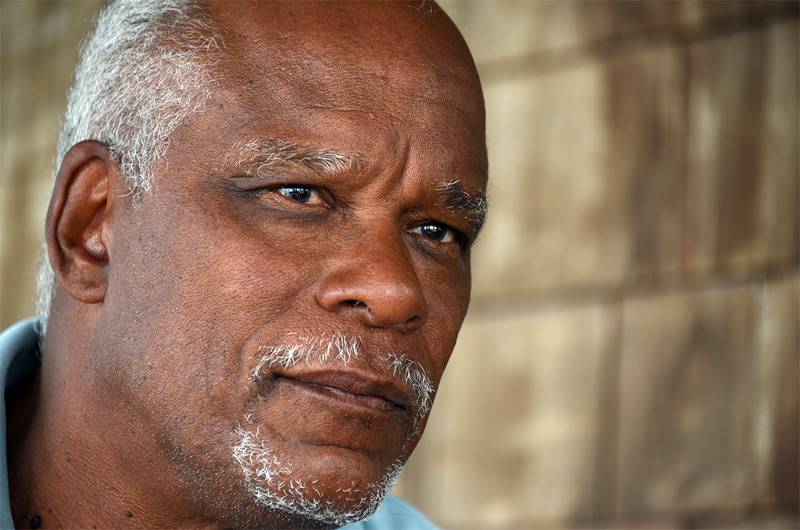

Stanley Nelson, a longtime seasonal resident of Oak Bluffs, has won multiple Emmys for his documentary films about the black experience, a MacArthur Fellowship grant and in 2013 received the National Humanities Medal from Barack Obama.

Last week he added Oscar nomination to his resume for his most recent documentary, Attica. The film was co-directed by Traci Curry.

“I kind of want to say to myself, oh, it doesn’t mean that much, it doesn’t matter that much, but it’s a real validation of the film,” Mr. Nelson said in a recent interview with the Gazette.

The Attica Correctional Facility was known as the strictest prison in New York state in 1971. The largely black prisoners were given one roll of toilet paper per month and routinely kept in their cells for more than half the day. The all-white guards were known to gang up and dish out brutal beatings.

It all boiled over on Sept. 9 when over one thousand prisoners rioted, took 39 prison employees hostage and controlled D Yard of the prison for four days. The ensuing stand-off and violent conclusion captured the nation’s attention.

“This film really punches you in the gut,” Mr. Nelson said.

The uprising ended when state police and prison guards shot and killed 29 prisoners and 10 hostages after negotiations stalled. State officials accepted 28 out of the prisoners’ 30 demands, but refused to grant them amnesty from future prosecution.

“There was no reason why Attica ended the way it did,” Mr. Nelson said. “There was no inciting incident—things didn’t get worse, things didn’t get better. They were negotiating.”

The riot laid bare a broader national tension, Mr. Nelson added. Many of the prisoners were part of the black power generation, which took a more radical approach to racial equity than their non-violent predecessors. On the other hand, the law and order movement had begun to push severe drug laws as the answer to urban crime.

“These two things are [at] opposite ends and they’re just really clashing in what happens in the Attica rebellion, and it leads to disaster,” Mr. Nelson said.

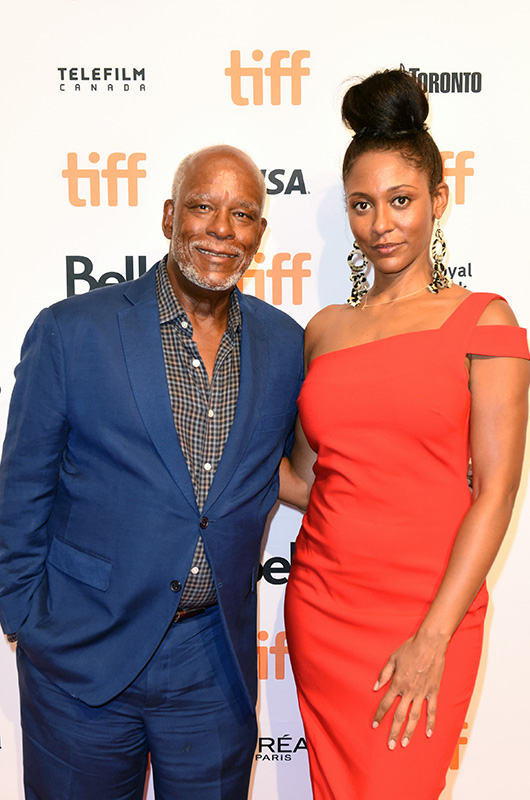

The film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival on the 50th anniversary of the riot. But that was a coincidence, Mr. Nelson said. He has wanted to make the film for 30 years, but it became more urgent when he realized the people involved, especially the former prisoners, were aging.

“If they were 20 years old on the [prison] yard . . . they’re 70 now, but 70 is a lot different from 80,” he said.

Like everything else during the pandemic, there were logistical hurdles to making the film. Mr. Nelson, whose film credits include movies about the Black Panthers, the Freedom Riders, the Tulsa massacre and the black experience in Oak Bluffs, said he has never seen anything like the archival footage in the film. But for a long time the archives which housed the footage were shuttered because of Covid.

“Making any kind of film is hard, making archival films are really hard and making archival films during Covid are triply hard,” Mr. Nelson said.

Mr. Nelson said he hopes the film humanizes the former prisoners because that was at the core of their demands during the riot.

“[In the film], you see that one of the former prisoners is funny, another one is a Muslim . . . other ones are strategic, other ones are very emotional,” he said. “You see that the prisoners are human beings.”

There are multiple lessons from Attica which resonate today, Mr. Nelson said. He hopes viewers draw those parallels without the film spelling them out.

“I think that’s one of the really powerful things about documentary film, it’s when the audience themselves connect the dots and you feel like, ‘oh [I’ve] realized something about today and about the prison system,’” he said.

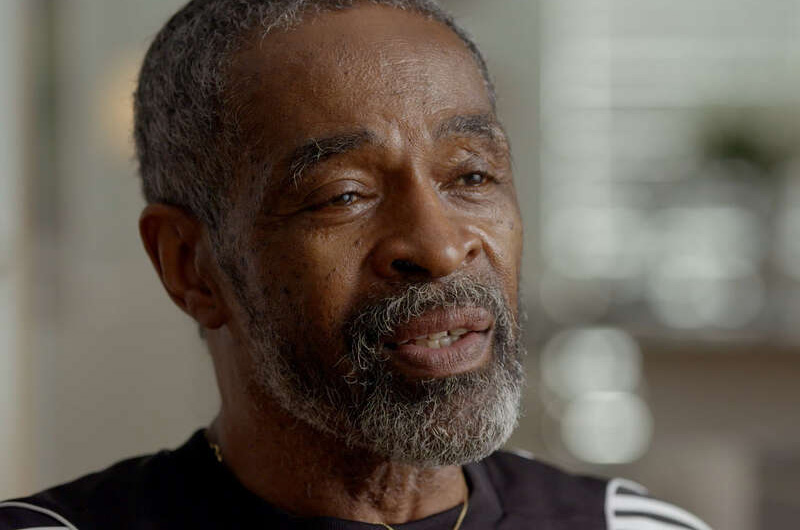

At one point in the film John Johnson, a black reporter who covered the riot for ABC News, recounts walking the yard and speaking with prisoners he knew from growing up in New York city. Mr. Nelson said he almost cut that part, but realized it showed the importance of diverse viewpoints.

“John Johnson saw those people as people he grew up with, and they were in Attica and he knew them as kids. Not to say that they didn’t belong in Attica, but it does mean something because he comes to a situation with a different set of experiences,” Mr. Nelson said.

The film also intentionally doesn’t talk about the current state of the prison system — which incarcerates over two million people, the majority of whom are people of color, Mr. Nelson said. In recognizing the humanity of the former prisoners, Mr. Nelson said he hopes viewers will do the same for today’s inmates.

“We lock people up and we forget about them,” he said. “You have to think about, hopefully, the two million individuals whose lives and productivity are being wasted on a system that is, in many ways, just antiquated.”

Comments (8)

Comments

Comment policy »