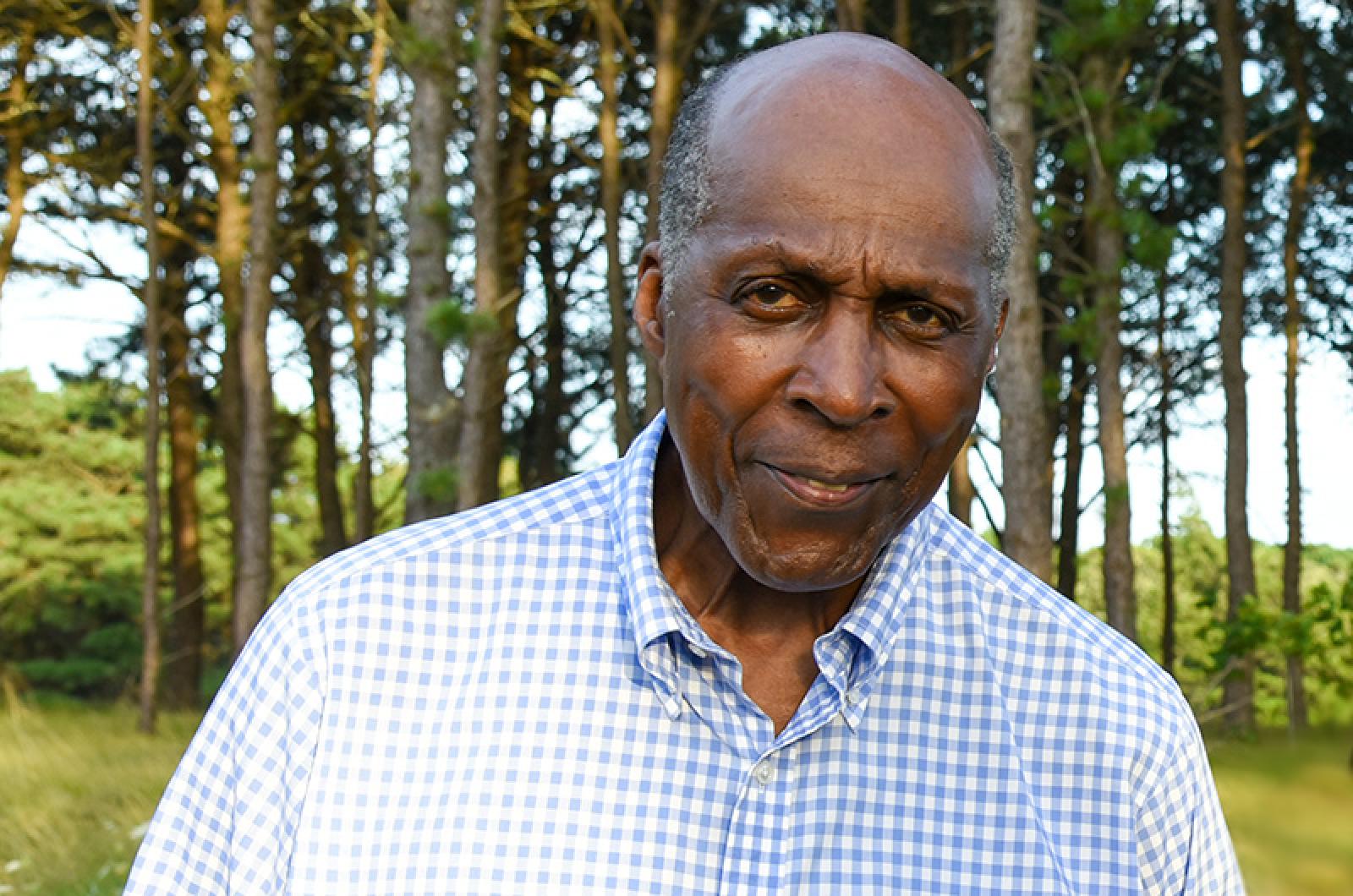

The clock radio blasted me awake. I cleaved to my pillow, bargaining with the alarm gods till the news came on. The top story for the day: Civil rights leader Vernon Jordan had been shot. Auto-pilot lifted me from my bed. It carried out my morning routines. It transported me from my Brooklyn apartment and onto the Lexington avenue subway. It sped me past newsstands with Vernon’s face and unnecessary innuendo all over New York’s daily scream sheets. It delivered me into my office building. It was Vernon’s office building too. My co-workers and I held our collective breaths and waited to learn if our boss would live or die.

When I first met Vernon a decade earlier, he was padding barefoot across the linoleum of a kitchen in Westchester County, N.Y. I was home from college for the holidays, and our holiday house guests were about to step out to call on their old friend from Atlanta. Vernon had just moved north to head up the United Negro College Fund. “Come with us, Shelley. You should meet him.”

In time, Vernon and his wife Shirley would share the same social circles as my parents, and by pure happenstance, I would work for five years under his command. In that kitchen moment though, all I knew of Vernon was this vision of a tall, energetic man with a headlight smile, cooking and conversing all at the same time. Secure in his bare feet, despite company. I did not meet Shirley that day; I would learn she was not in the best of health. Their daughter Vickee, a quiet big-eyed girl of 11 or 12, came to the kitchen door for polite introductions to the visiting grownups, then vanished.

I landed at the National Urban League as a young professional in the mid-1970s, a heady time in its history. Executive director Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. was a rising star. His public statements made national news. U.S. presidents never turned down his invitations to appear at our annual conferences. Fortune 100 CEOs — gray-haired white men who could no doubt make their own troops quiver in fear — would become as giddy as groupies in the presence of Vernon’s charm.

Yet the high and mighty were of no higher interest to Vernon than, for example, a banquet server he once recognized at a distance from a speaking podium in a packed Atlanta ballroom. She had been his high school classmate some 30 years prior. He left the dais, walked across the floor and gave her a hug.

She was one of hundreds if not thousands of Vernon’s close acquaintances over the course of his life. For even if you first met Vernon in a crowded room, you and only you held his entire focus, if only for a moment. Whether you were a somebody, a nobody, a codger or collegian. And if you happened to meet again years later, chances were good that he would remember both you and your story: How’s your father? Are you still in Chicago? Please tell so-and-so I said hello.

His antennae were of the highest frequency. Returning to the office from a meeting or speaking engagement, he often reflected out loud on who showed up and who didn’t. Who didn’t look him in the eye. Who didn’t greet him. Vernon had a thing for detecting who was a person of honor and who was not. Who kept his or her word. Who had integrity. He took the measure of a person.

Celebrity or not, he was simply the boss to us foot soldiers — likable, regular and occasionally vexing. But we were never vexed for long. At a memorable staff meeting, he announced there would be no cost-of-living increase in our salaries the following year. In the next breath, he announced that the board of directors had just approved a sizable raise for himself. He said this with his signature transparency and, above all, closure. He was unapologetic. The mystifying thing was, he sold it.

One hundred days would pass before Vernon returned to the office after the shooting. His cheeks were hollowed. His tailored suits hung from his frame like sails without a breeze. Yet he was in glad-to-be-alive spirits, and so were we. Nevertheless, the whispers that had floated about the office during his absence would prove true. A year later, he left the Urban League and turned in utterly new directions in his career and life. Because life is short.

I stopped by his office a day or so before his departure. I owed him a thanks for a couple of past favors in the name of office politics. I had never asked Vernon for these favors, nor did I know for absolute fact that he performed them. But I too have pretty good antennae. When I simply told him I had appreciated his support over the years, he smiled knowingly. And verbally boxed my ears for never asking him for any help in the first place. For not engaging him as my power broker. He had risen to a level of influence rarely attained by a black man in America. I was apparently deemed worthy of that influence, and I didn’t avail myself.

“You’re just like my daughter Vickee,” he said. “You girls insist on being independent.”

Vickee’s Washington D.C. wedding was an old-school affair, with a guest list heavily laden with her father’s close acquaintances. At the reception, after guests had taken their seats, I spotted Vernon alone outside the ballroom, head cocked over a table. He was peering at a few remaining place cards. Taking account of who was not there. Who was not a person of his or her word.

If there’s a heaven, Vernon knows who live-streamed his funeral and who didn’t.

Rest in peace.

Shelley Christiansen lives in Oak Bluffs.

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »