Weather models may be able to predict how bad storms will get due to climate change, but according to architect Matthijs Bouw the key to preparing for the future is not infrastructure but social infrastructure.

Mr. Bouw is a Dutch architect whose firm, One Architecture, has taken a people-centered approach to climate change planning. His clients include New York city, with a focus on projects in lower Manhattan and Harlem.

He is also an advisor to the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Climate Action Task Force and on Monday he took part in a talk hosted by the MVC, one of a series of events scheduled over the next few months in the run-up to Climate Action Week in May. The talks are organized by Liz Durkee, the climate change planner for the MVC.

“It’s all hands on deck if we want to succeed in becoming a climate change resilient Island,” Ms. Durkee said at the start of the talk.

Mr. Bouw focused his presentation on his work with New York city, that island to the south of the Vineyard.

“What I’d like to do today is not talk so much about Martha’s Vineyard, but talk a bit about my practice and the practice of climate adaptation in general,” Mr. Bouw told the Zoom audience.

Hurricane Sandy alerted New Yorkers to the reality that lower Manhattan is a sitting duck for coastal flooding, Mr. Bouw said. One Architecture was tasked with figuring out how to protect the areas most at risk of being submerged.

Mr. Bouw said he and his team drew inspiration from the High Line in Manhattan’s west side, an elevated rail line which was turned into a public park.

“What’s interesting about that, we thought, is that when you build infrastructure we should not only look at that from a sort of technical perspective, but we should see if we can combine it with programs so that it becomes something for the people,” he said.

He continued: “[We decided] we needed to build a resilience infrastructure that is not there only for those few moments that the city is at risk of flooding, but that it should be really something that is there for the people at all times.”

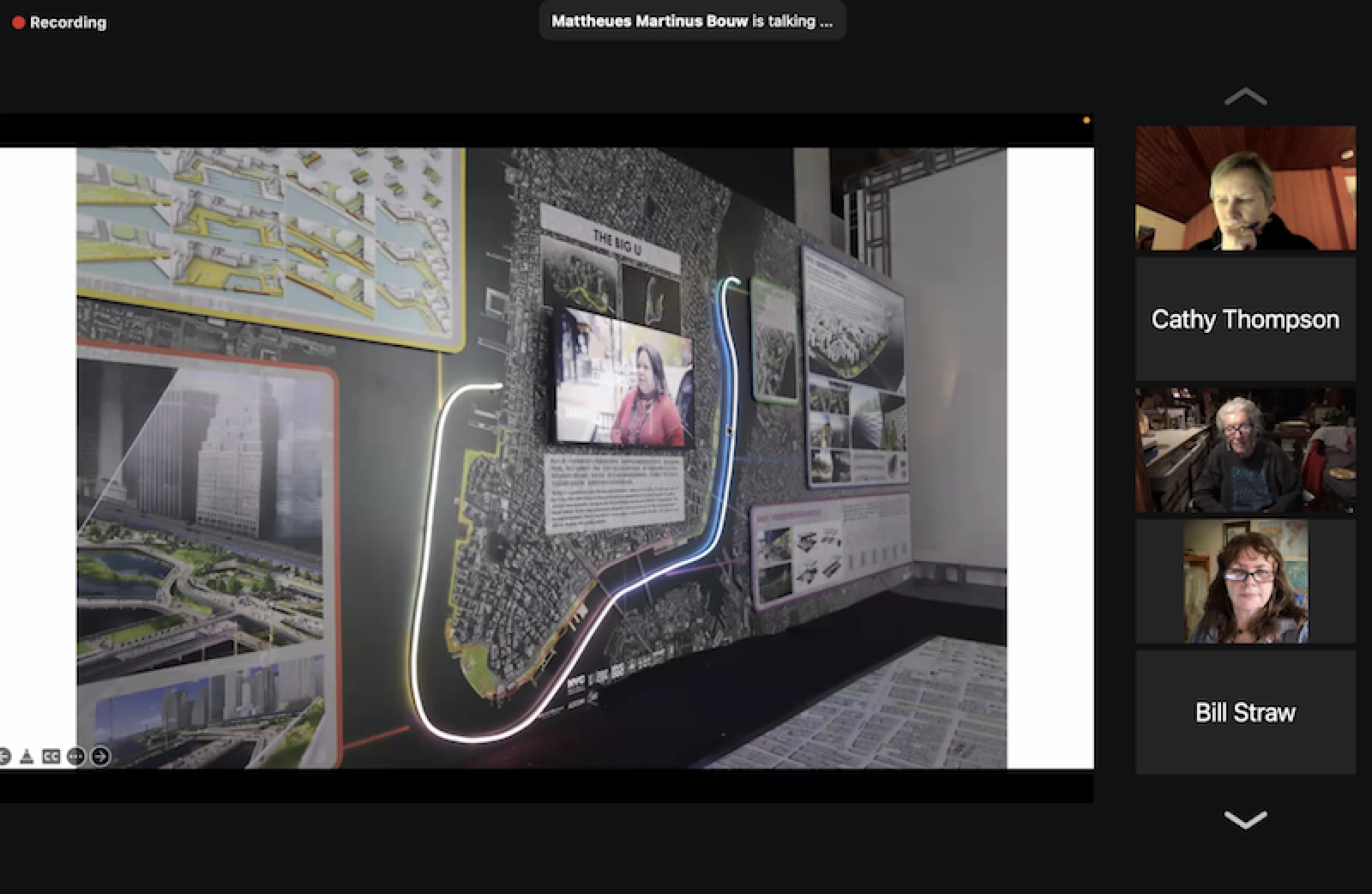

That thought led to a proposal called the Big U, which is a plan to adapt 10 miles of coastline in lower Manhattan vulnerable to flooding.

“[The Big U] is a sort of infrastructure project that is tailored to its different communities,” he said. “For us, the idea was to say, infrastructure needs to be social infrastructure, and that means we need to develop a social infrastructure together with all the different stakeholders.”

There is no blanket plan for the target area, he said. Instead, projects are segmented and tailored to fit the desires of the people they will be serving. One example he presented is a plan to rethink the one-mile waterfront at the city’s financial district. The idea is to weave flood protection infrastructure in with an extended shoreline and newly built open space for public use.

Involving stakeholders whose lives will be affected is central to building social infrastructure, Mr. Bouw said. He gave as an example a resilience project in East Harlem, which is unrelated to the Big U. The One team partnered with a local school, the Harlem Dream School, to develop a curriculum to teach students what the city is doing to deal with climate change and expose them to career paths related to resilience.

“In this project, we said we really need to make sure that we build, in this neighborhood, the social capital to build the resiliency infrastructure,” he said.

In closing remarks thanking Mr. Bouw, Ms. Durkee emphasized this social aspect of building infrastructure.

“I think that’s so important on this Island, and everywhere, to include people in the solutions when we’re looking at these issues,” she said.

Comments

Comment policy »