When my father Doug Ewing died from cancer in 1995 I was not yet five years old. When a parent dies and you are that young, you lose more than just the person. I have some memories of my father before he died, but they are the scattered and dubious memories of a four-year-old. I missed out on so much, including the big fight you are supposed to have as you grow up that results in a new relationship, from parent and child to that of two adults.

My journey to Japan from the Vineyard in mid-November was an attempt to meet my father as an adult, and to learn who he was as a twenty-something. He had left the Vineyard and the country on a study abroad program, taking classes through Sophia and Doshisha Universities in Tokyo and Kyoto, respectively. It was 1973 and he was 20 years old.

Over the years, through research and some deduction, I pieced together a timeline of my father’s life in Japan. I scoured his box of artifacts and souvenirs for names and addresses and started sending letters into the void. When I received a reply from the city of Hirakata-shi, welcoming me to visit, I knew it was time to start a project I had been planning for a long time. In one sense, I would be a son retracing the footsteps of his father, but I would also be an artist reinterpreting the past through new images and meaning.

I found the addresses of the classrooms where my dad had attended courses. I found the student dormitory where he had stayed in the former Olympic village in Tokyo, and I tracked down the landscaping company in Kyoto he had interned for. I planned to stand where he stood and make new photographs of the places I had seen only in the little snapshots he had taken and brought home with him.

But the heart of the trip would be meeting Takatsune Nakamura, a man who knew my father when he was a college student trying to make his way in the world. Who better to tell me about the young man I was trying to get to know better?

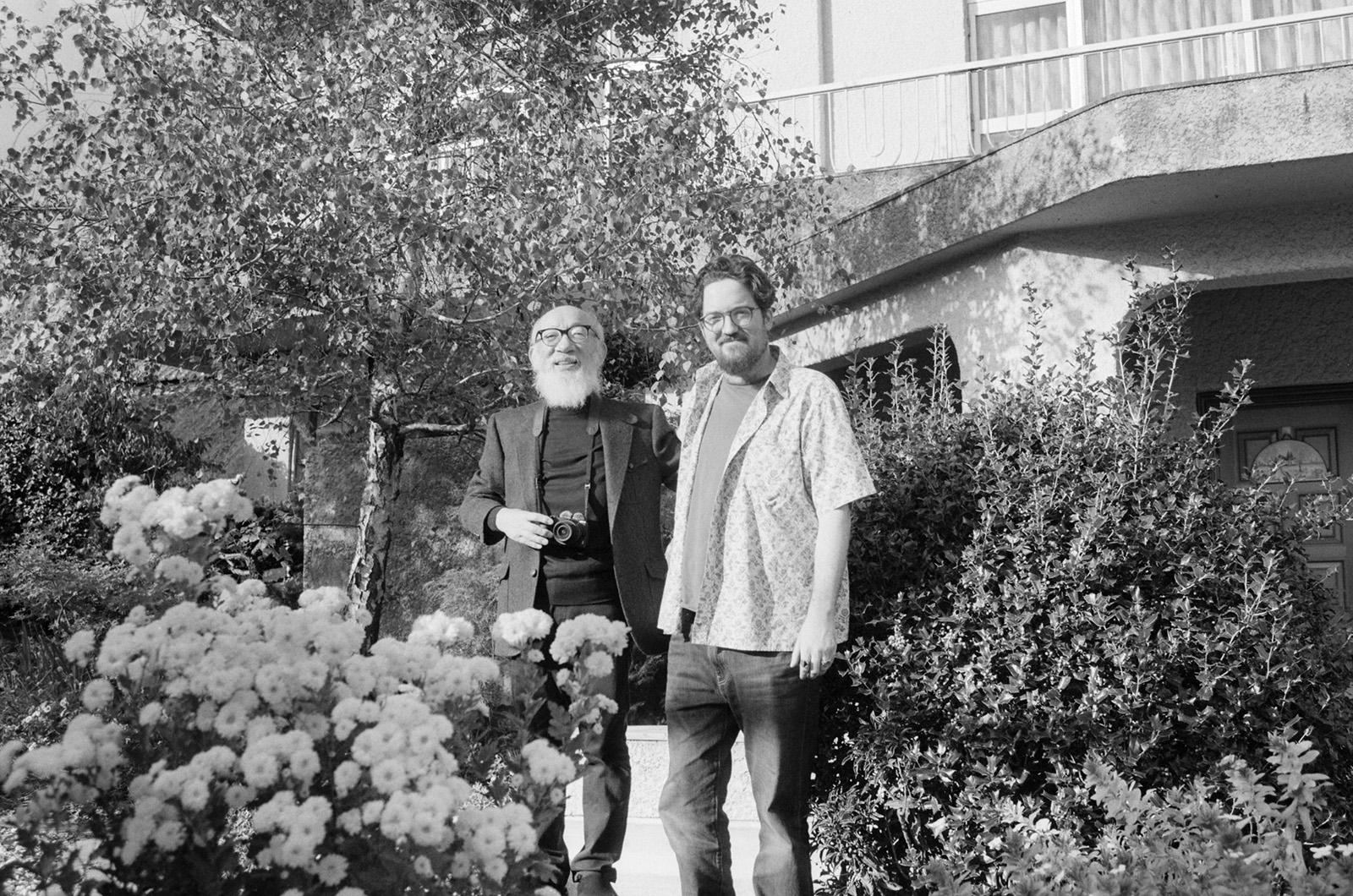

I met Takatsune in the Kasuga Taisha shrine in Hirakata, where he is head Shinto priest. He is in his late sixties now, with a long white beard. He greeted me with a big smile and then began reciting prayers of blessing, safety and good fortune for our group and our travels. He included my name, the name of my fiancee Kate and our friend Spencer who was our guide and interpreter while we were in Japan. The onusa (wooden wand) was brought first to the Kamis [spirits] and then to our heads to purify us. Then the Suzu bells were rung over our heads to direct the power of the Kamis to us.

Spencer quietly translated the prayers into English while Kate tried to hold back her tears. I realized I was finally at the place where I hoped this journey would take me. I had discovered a fissure in time, a passage through which I could extend a hand toward, or steal a glance of, my father.

Takatsune then gave us the Ema [wooden plaques] to write our names and the date, all to be burned later. I have no connection to the Shinto tradition or Japanese spirituality, but I did have a connection to the man in the flowing purple robes who stood in front of me. For my whole life I have treasured a small box of souvenirs and letters my father brought back from Japan. In those letters, he spoke of the Nakamuras who brought him into their home and prepared him for exploring Japan. The letters, bus maps, school journal notes and aerogrammes my father saved painted a partial picture of a young man in a foreign land coming to terms with himself as he navigated a different culture.

Once the private ceremony was finished, Takatsune gestured for me to follow him to another area of the shrine grounds. Spencer followed and translated that Takatsune wanted to show me where my father invented the game of one-base baseball 50 years ago. I could feel Takatsune’s excitement as he told me the story about my father and his insistence that they find a way to play baseball. He explained that because there was no field nearby, and the shrine grounds were the only space available, the traditional four bases were not possible, thus one-base baseball.

“There is still a baseball somewhere in that bamboo that your dad hit 50 years ago!” Takatsune exclaimed. “He was very powerful!”

We decided to reenact the fateful game on this 50th anniversary, but with a new twist: we had no bat or ball and so it was imaginary one-base baseball. I mimed hitting a home run off a pitch from this Shinto priest I just met on the grounds of his shrine, and at that moment I never felt more connected to the memory of my father. As the imaginary baseball flew toward me, I could see it become real, see the bat appear and see my 20-year-old father appear in my place as 50 years melted off Takatsune as well.

When my invisible bat connected with the invisible baseball, a big smile spread across Takatsune’s face. And as I pretended to watch the ball fly off into the bamboo, I was sure it found the same resting place as my dad’s baseball.

“Now we can go to my home and talk about your dad. My wife has made a few snacks,” Takatsune said.

The “snacks” turned out to be a two-hour feast that his wife had been preparing all day.

Over lunch, we heard how the “powerful” — there’s that word again — Douglas would walk two kilometers every day to the train station, and how the skinny Douglas returned at the end of a trip around the country and accidentally ate all the beef meant for the whole family. We heard about a rumored girlfriend but not her name, perhaps to protect her privacy.

After more food and memories and stories, we thanked our hosts and exchanged the customary gifts. It was only then that Takatsune asked me a question that I imagine he had been waiting the whole time to ask.

“How did Douglas die?” he asked.

I took a breath and explained that he had contracted melanoma that had spread to the brain.

Takatsune paused and then bowed, uttering a blessing. There was a brief silence before he pulled out some old photos that my father had sent him many years ago. Takatsune asked me to name my dad’s parents and all of his brothers.

We continued to talk and Spencer explained the artistic and personal goals of my project to which Takatsune smiled and nodded. He then showed me the room my father slept in and the various spots around the house where he had taken pictures. As I was recreating a portrait of my father lounging with a newspaper in front of the grand piano with myself in his place, Takatsune pointed at me and said: “It’s Douglas!”

Apparently my mannerisms and “poses,” as Takatsune explained, were so reminiscent of my father that he had to point it out.

The day was a gift for both of us, a time where I felt the spirit of my father along with his old friend. On the ride back to the train station — we did not walk the two kilometers — I tried to explain more through Spencer about my intention to spin pieces of memories and artifacts into a new adult portrait of my father.

Nakamura-san smiled and gave me a piece of advice: “If you are looking for your dad, look in the mirror.”

Comments (17)

Comments

Comment policy »