In 1842, John Thompson was looking for a way to flee the United States. An escaped slave, he had made his way from a Maryland plantation to a fragile freedom in Philadelphia. Fearing recapture by slave traders he continued northward to New Bedford where he found work as a ship hand aboard the Milwood, captained by Aaron Luce of Tisbury, Martha’s Vineyard.

The story of Mr. Thompson, who recounts befriending Mr. Luce in his autobiography The Life of John Thompson, is one of dozens featured in Sailing to Freedom, a new exhibit at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum which considers the Underground Railroad’s lesser known sea routes and their connection to Martha’s Vineyard.

Kate Logue, assistant curator at the museum, said the exhibit aims to “expand people’s understanding of the Underground Railroad.”

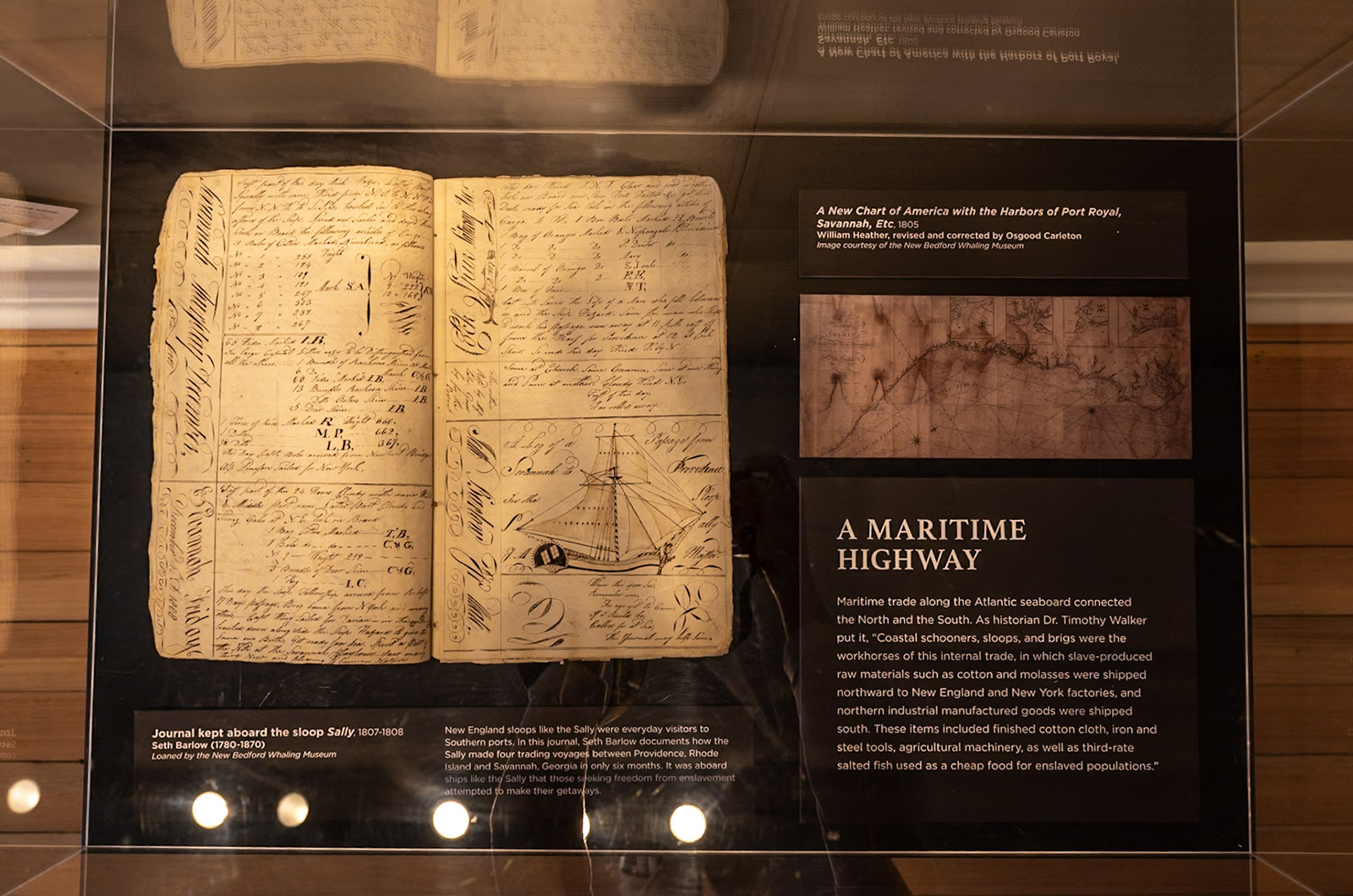

In the antebellum period, travel to freedom overland was available only for a handful of enslaved men and women living in states such as Maryland and Virginia, Ms. Logue said. Travel by sea, especially by the freight vessels that carried commercial goods up and down the Atlantic, was a more readily available means of escape.

“It was really the only practical way for those who were enslaved in the deep south to escape and reach freedom in the north,” Ms. Logue said.

“Today, we have cars, we have trucks, we have airplanes — we don’t realize how integral the maritime world was to everyday life at that time, how it linked the north and the south,” Ms. Logue said. “There were ships going back and forth, from the north and the south every day with people with cargo.”

Northern sailors, merchants and shipowners sympathetic to the cause of abolition helped ferry enslaved men and women to freedom. Once in the north an escaped slave could, like Mr. Thompson, set out on whaling vessel expedition or other type of ship that would carry them far out of reach from slave-catchers for years at a time, Ms. Logue said.

Sailing to Freedom is a traveling exhibition built upon research conducted for an essay collection of the same name edited by Timothy Walker, professor of history at Dartmouth College.

After Mr. Walker approached the museum about featuring the exhibit, Ms. Logue began gathering materials that would connect it to the Island’s history. Mr. Walker will give a talk at the museum on June 21 at 2 p.m., elaborating on the exhibit and the essays that inspired it.

The historical record preserves some confirmed instances of Vineyarders playing a part in the seaward journey of the Underground Railroad. The exhibition details, for instance, the case of Edinbur Randall, a formerly enslaved man who was hidden by members of the Wampanoag tribe in Aquinnah after he had been discovered in Holmes Hole Harbor. Beulah Vanderhoop, of the Aquinnah Wampanoag, eventually helped smuggle Mr. Randall to freedom in New Bedford.

“In doing research, I tried to expand and flesh out what I could,” Ms. Logue said.

The task proved challenging — the Underground Railroad, like most illicit institutions, tried its best not to leave any records.

“I tried to weave a thread throughout the exhibit about how it can be so challenging to uncover these stories because it was a covert act,” Ms. Logue said.

She also hopes the show draws attention to the men and women themselves who took extreme risks to pursue freedom.

“A lot of the stories I had been told focused a lot on the Underground Railroad as doing all the work,” Ms. Logue said. “But people took their own initiative to conceal themselves, or develop resources so that they could bribe someone to help get them north.”

Pouring through the ship’s logs, diaries, narratives and runaway advertisements that make up the fragmentary historical record, Ms. Logue was constantly reminded of the tenacity and resilience of the slaves who pursued freedom in the north — along with the brave souls who helped ferry them to a new life.

Sailing to Freedom a the Martha's Vineyard Museum runs through Sept. 22.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »