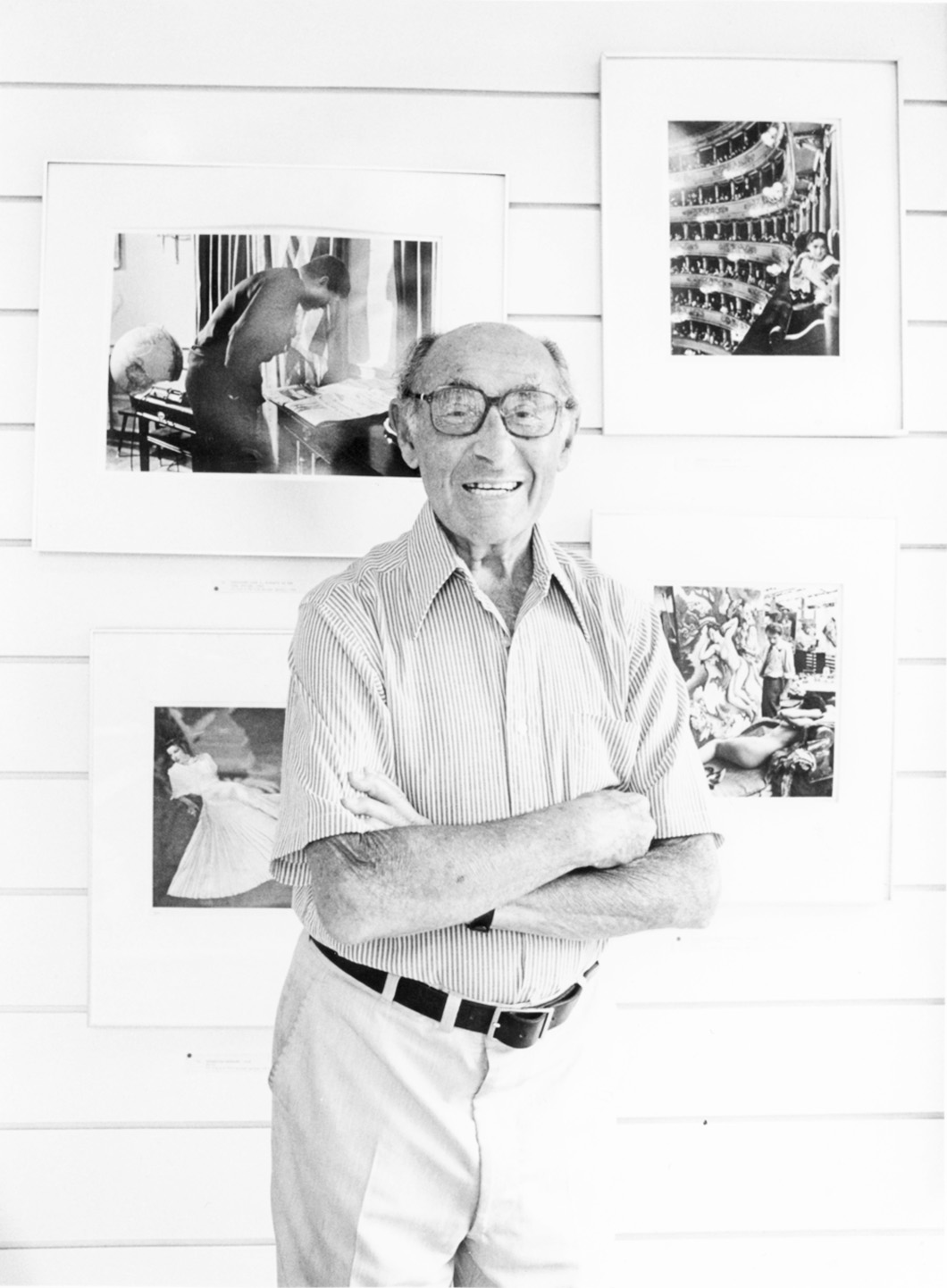

Famed photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt’s lingering presence on Martha’s Vineyard is sometimes easily apparent to the eye, other times lurking behind the scenes.

A new Martha’s Vineyard Museum exhibit, Eisenstaedt’s Martha’s Vineyard, is the latest iteration of the photographer’s life on the Island, nearly 30 years after his death in August of 1995 at his summer cottage in Menemsha.

Photographs from the museum’s collection are complemented by others on loan from Granary Gallery owners Chris and Sheila Morse, former Tisbury selectman Denys Wortman and wife Marilyn, and audio interviews with Eisenstaedt done by oral historian Linsey Lee.

The exhibit complements an already rich tapestry of Eisenstaedt’s imprint, talents and perspectives, quietly woven throughout the Island that he fell in love with while on assignment as a new photographer for Life Magazine in 1937.

A look through the Vineyard Gazette’s archives reveals numerous presentations given by Eisenstaedt himself at Edgartown’s Old Whaling Church, the Old Sculpin Gallery and West Tisbury First Congregational Church, where he regaled residents about real war stories and experiences with Hollywood’s biggest stars, along with his travels around the world. There are the coffee table books he published with local author Polly Burroughs and former Gazette editor and publisher, Henry Beetle Hough.

The Granary Gallery features nearly 100 Eisenstaedt photos and what Mr. Morse calls a “very active secondary market” of prints, all a byproduct of a long friendship with Eisenstaedt that began when Mr. Morse was a teenager.

Working summers at the gallery in the late 1980s, “I used to pick him up at the Menemsha Inn in my 1974 jade green BMW,” Mr. Morse said. “He needed a bit of help then. When he’d have a new book come out, I’d bring cases of them to the cottage to sign. [Sister in law] Lulu [Kaye] would make lunch, and I’d help him organize the books. He had an old clock in front of him, he’d keep track of all the time he spent, signing them from ‘Eisie.’”

The Menemsha Inn maintains a shared space called the Eisenstaedt room, with a black and white photo of him hanging on a wall above a bookcase. Eisenstaedt died at his beloved Pilot House cottage, where he stayed every year, at the age of 96, with Ms. Kaye his side.

Today, a walk through the remodeled cottage, situated on the northeast portion of the property leading down to the Sound, reveals a still rustic outdoor shower and unadulterated view of the woods and the ocean.

It was a snapshot Eisenstaedt was well aware could slip away, he told the Gazette in July 1975.

“I used to walk in the morning, from the Menemsha Inn to the Bight and photograph before people woke up, for this is the time when it is very still,” he said at the time. “But you can’t do that any more....Now the marina is there. Wires strung everywhere. Electric poles. This is what they call progress!”

While he was, largely, on vacation here, Eisenstaedt could never sit still or put his passion down for more than a few moments.

Island photos featured in the Martha’s Vineyard Museum exhibit include the First Boat in Three Days, an image of a ferry cutting through a layer of ice in 1961; Mrs. Napoleon Madison, a schoolteacher, columnist and member of Aquinnah’s Wampanoag Tribe; a shot of the Gazette’s production room as the newspaper goes to press in 1952; and of square dancing lessons for Island children in the garage of Shirley Kennedy.

Eisenstaedt also photographed President Bill Clinton vacationing on Martha’s Vineyard in 1993, and Walter Cronkite battling it out on the tennis courts at the Edgartown Yacht Club in 1975.

Born in West Prussia, now Poland, in 1898, Eisenstaedt began his professional career in the Berlin office of the Pacific and Atlantic Picture Agency, which later became part of the Associated Press, in 1929.

Early notable pictures include an ice skating waiter at the St. Moritz Grand Hotel, glowering Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (who had learned Eisenstaedt was Jewish just before the shutter clicked), and the first meeting of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Italy.

In 1935, oppression in Nazi Germany brought Eisenstaedt’s family to New York. He was hired by Life as one of the magazine’s original four staff photographers in 1936, a position which he remained at through 1972, with more than 90 pictures appearing on the cover during this span.

“He had just arrived in New York and came to the Vineyard for one of his first assignments,” exhibition curator Anna Barber said. “He very quickly was introduced to, and fell in love with, the Island.”

Ms. Barber said she asks exhibit visitors to travel back to a time when smartphone cameras weren’t so ubiquitous.

“Magazines at this time were the way people were seeing images,” she said. “Life was one of the most popular. The fact that people all over the world were seeing the Vineyard through his eyes makes them look at these images in a different way.”

Utilizing a hand-held Leica camera for its flexibility, Eisenstaedt’s photos make use of natural light, often capturing people in action in their natural environments. A sailor famously kissing a nurse as he dips her in the midst of Times Square during V-J day is a case in point, as are children reacting with joy to a Parisian puppet show in 1963.

He credited his hands and his eye over the camera itself.

“Can you feel at ease with this thing staring at you?” he remarked to the Gazette in 1952. “No? I make them feel at ease. I do not handle lights, I do not stare at people or ask them to smile. I talk about people we know, about things of interest. Often when I am through and packing my equipment, they ask, when are you going to begin? They never noticed the camera.”

The exhibit runs through August 25. For more information, visit mvmuseum.org.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »