The chasm may not be closed. But for many Islanders it got a little tighter on Tuesday, when the Oak Bluffs selectmen voted unanimously to adopt the Martha’s Vineyard NAACP’s recommendation and remove two plaques from a Civil War monument that contain language honoring confederate soldiers.

“I’m proud of the Oak Bluffs selectmen,” said a jubilant Dr. William McLaurin after the decision. “It’ll be good.”

For two months, the selectmen have demurred on taking a public stance on the two plaques on the statue that stands at the entrance to Ocean Park. The plaques — one on the southern face of the monument, and another on the ground — reference confederate soldiers.

Instead selectmen have listened quietly to what has grown into a heated public debate about history, memory and preservation on the Island.

After nearly two hours of testimony at a public forum the board had called Tuesday, the selectmen decided to act.

“I’ve come a long way in this process,” selectman Michael Santoro said. “As we met, I grew. I understood . . . but this forum tonight was very educating. I want to thank everybody for coming. It took a lot of bravery.”

Selectman Greg Coogan made a motion to remove the plaques and create a committee that includes the NAACP, the Dukes County Veterans association, and the Wampanoag tribe, among others, to come up with an appropriate historical replacement. The plaques will go to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, which has agreed to accept them into their collection.

Mr. Santoro seconded the motion. It was adopted unanimously.

“Let’s move forward,” selectman Jason Balboni said, just before an outpouring of emphatic applause from the packed cafeteria at the Oak Bluffs School.

During testimony people strayed beyond remarks about the monument and spoke about their personal relationships with race, memory, war, and with Martha’s Vineyard. It was a history lesson on the nature of historical remembrance itself.

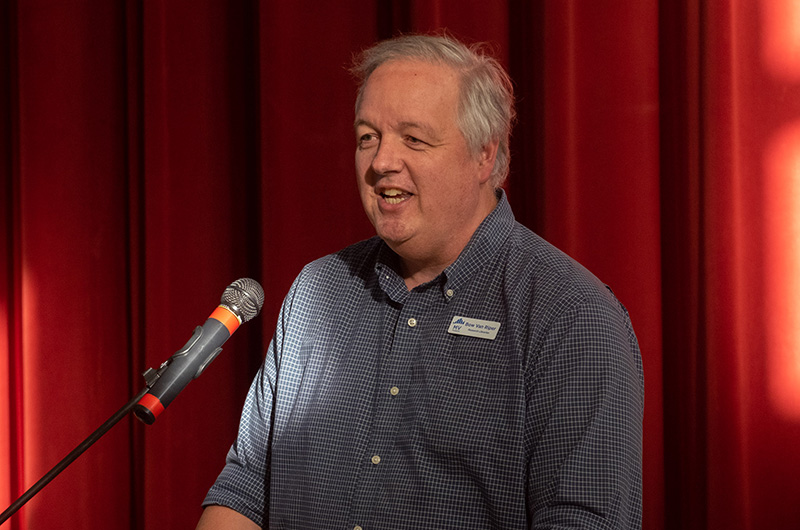

Archivist and librarian for the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, Bowdoin Van Riper, opened discussion by framing the statue in the shadow of the Civil War and the background of race-relations in the early 20th century.

The statue was dedicated in 1891 by Charles Strahan, a former confederate soldier who moved to Martha’s Vineyard after the war. Although Mr. Strahan fought for the South, the statue depicts a union soldier and was meant to honor those who fought to abolish slavery, “closing the chasm” of bitterness that remained from soldiers on opposite sides of the conflict. The plaque in question, which was added to the statue in 1925, reads: “The Chasm is Closed / In memory of the restored Union this tablet is dedicated to Union veterans of the Civil War and patriotic citizens of Martha’s Vineyard in honor of the Confederate soldiers.”

For Mr. Van Riper, and almost everyone else who spoke on Tuesday, the words did not necessarily ring true nearly 100 years later.

“This is where wording matters,” Mr. Van Riper said. “The architects of the fourth plaque reached for a sweeping statement of healing and reconciliation, one which they might have felt deeply and intensely . . . but they made such a statement at a time when, for African Americans in Oak Bluffs and elsewhere, the chasm was far from closed.”

He described how the West Tisbury school held minstrel shows as fundraisers, how the Island remained segregated into the 20th century, and how even black Americans in Oak Bluffs, which grew to have one of the largest African American summer communities in the country, experienced the pangs of racism in the aftermath of the Civil War.

“History is complicated,” Mr. Van Riper said. “Anyone who is telling you different is selling something.”

Selectmen listened intently and took notes as Islander after Islander, from wash-ashores to Wampanoags, from Oak Bluffs summer residents to members of the town’s year-round community, from those who have never touched a gun to Navy veterans, stood to request the removal of the plaques. All echoed a similar sentiment, saying the time for change is now.

“This is a portrait of ourselves that we are holding up . . . We were the first state to legalize slavery,” said Clennon King, an Oak Bluffs summer resident who initially proposed removing the plaques this March. “I am no fan of the Patriots organization but what does Bill Belicheck say? Do your job,” he told the selectmen.

Others who spoke praised the diversity of the Island and Oak Bluffs in particular, describing the plaques as an unnecessary “black eye” that doesn’t represent that town’s otherwise open and inclusive character.

“This is why I came to Oak Bluffs as a permanent resident,” said Richard Cohen, representing the Hebrew Center of Martha’s Vineyard social action committee. “I came here because of the diversity the inclusiveness and I’m hoping that you all make us proud.”

Members of the Island NAACP, like Gretchen Tucker-Underwood, Oak Bluffs police chief Erik Blake, and Dr. Thelma Johnson, all advocated for plaque removal. Ms. Tucker-Underwood said it was unconscionable to continue honoring confederate soldiers. Chief Blake described how the status of confederates as veterans was little more than a symbolic gesture that allowed their widows and ancestors to receive financial support from the government. Dr. Johnson emphasized how 2019 represented the perfect time for a change, as it marked the 400th anniversary of West Africans being brought to the Americas as slaves.

“The time is now to do the right thing,” she said.

And while some Island veterans had opposed removing the plaques, there was an easing of that stance on Tuesday night.

Tom Rancich, who served combat duty in the Navy, described how his experiences on the battlefield informed his position.

“I can tell you stories that will make you all cringe,” Mr. Rancich said. “I can tell you about the horrors of what men do to each other...I am glad my sons will never see what I saw. I think those memorials ought to be removed.”

Jo Ann Murphy, the Dukes County veterans agent, told selectmen the veteran’s association would be willing to work with the NAACP, the Wampanoag Tribe, and others to put something in their place.

“Even though we feel that they are veterans,” Ms. Murphy said, describing confederate soldiers, “we need to close this. We need to make this right between all parties. I would be willing to work with Mr. Van Riper to put something in that place that everybody can agree on.”

After the vote was made, members of the veterans association shook hands with members of the NAACP, expressing a willingness to work on a commemorative plaque that described not only the history of the monument — but the history of the decision to change it.

“You opened the covers tonight,” Oak Bluffs resident Russell Ashton told selectmen.

“This was a history lesson that will never be forgotten.”

Comments (21)

Comments

Comment policy »