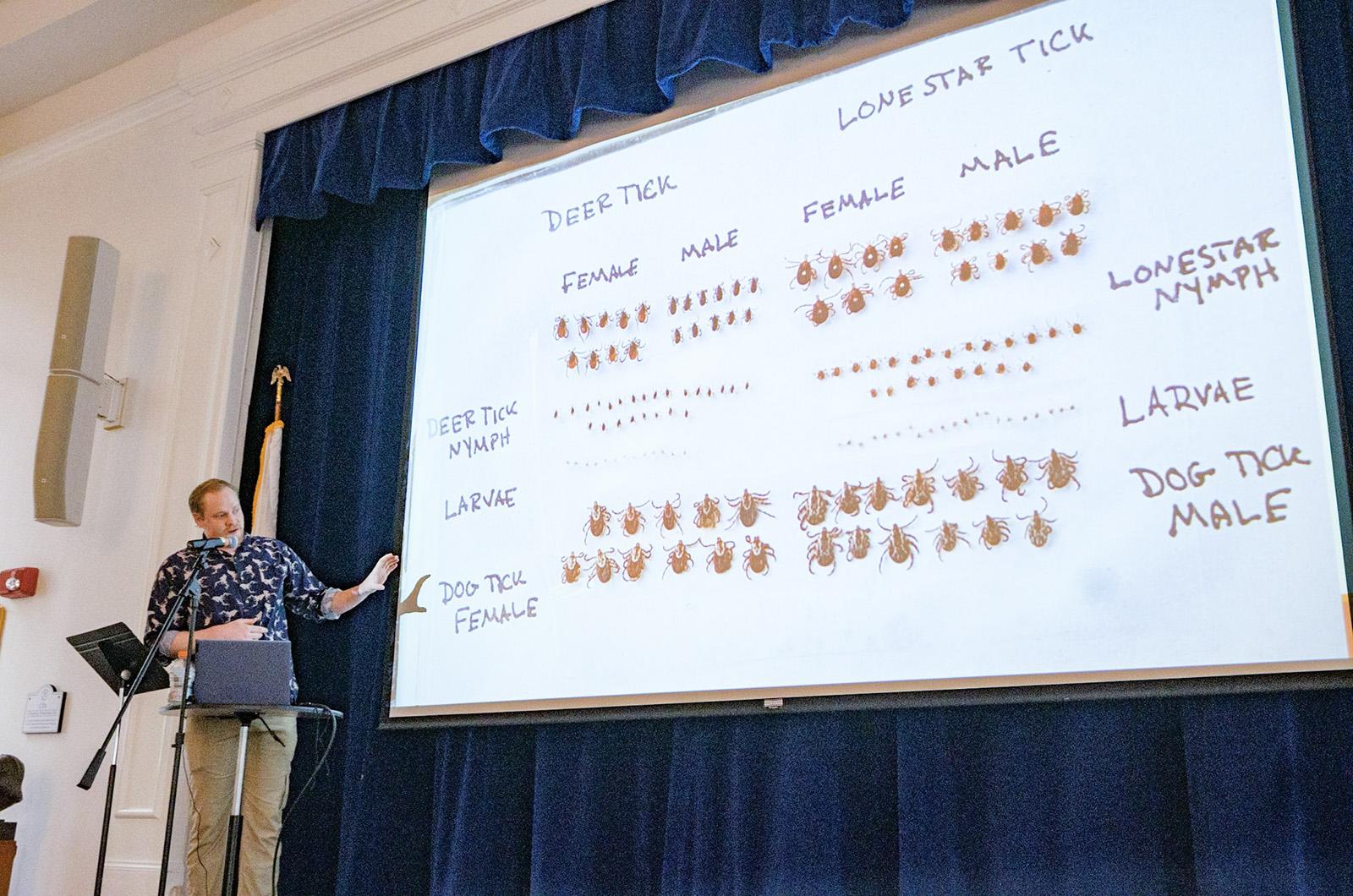

There’s no safe haven from disease-carrying ticks on Martha’s Vineyard, public health biologist Patrick Roden-Reynolds told an audience of about 85 people in Vineyard Haven Saturday morning.

At a half-day long tick-borne illness symposium put on by several local health groups, experts warned of the ticks presence across the Island and gave tips on how to keep an eye out for them.

As the head of the Dukes County tick-borne illness prevention program, Mr. Roden-Reynolds said deer ticks, lone star ticks and dog ticks have become so widely distributed that the risk of a tick bite now exists year-round in every Island town and neighborhood.

“Unfortunately, I’ve been finding ticks within mowed lawns, short-cropped, clean, manicured lawns,” he said at the event held at the Katharine Cornell Theatre.

“It’s honestly easier to tell you where the ticks aren’t,” Mr. Roden-Reynolds said, noting that he’s found fewer of the arachnids on wood chips and hard surfaces.

Tick bites can transmit pathogens for Lyme disease, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, anaplasmosis and other serious illnesses, said infectious disease physician Robert Smith of the Maine Medical Center in Portland, another speaker at the event.

“A lot of them look the same way when they start,” Dr. Smith said. “Coming into the clinic, you’re not going to be able to tell [which].”

A skin rash is one tell-tale symptom, he said, but it may not necessarily resemble the bull’s-eye rash associated with Lyme disease.

Any flat, round lesion of the skin is suspect, Dr. Smith said, whether or not a tick bite was identified.

“Remember, it’s the tick you didn’t find that’s probably going to cause the more trouble,” he said.

And biting isn’t the only way that ticks can sicken or even kill you, Tufts University tick expert Sam Telford told the audience.

Vineyard ticks also spread tularemia by carrying Francisella tularensis, a bacterium so virulent it was developed for chemical weaponry by both the Soviets and the United States during the Cold War.

“It’s one of the most infectious organisms we know about. Only 10 bacteria are sufficient to infect a human,” Mr. Telford said.

F. tularensis can survive after the death of its host, which is often a rabbit, he said.

When the carcass is disturbed, the bacteria then become airborne and infect mammals that inhale them — often people doing landscape work with powered equipment, such as mowers, Mr. Telford said.

Tularemia can be severe, disabling and even life-threatening.

“You feel like a train has hit you all of a sudden,” Mr. Telford said, adding that the disease causes liver damage and requires a long recovery.

With the Vineyard producing 7 to 10 per cent of the nation’s tularemia cases every year, respirator masks and goggles are key safety equipment for mowing, blowing and raking, he told the audience.

Personal protection is the approach Mr. Roden-Reynolds endorsed for tick-bite prevention as well.

“That is where you want to focus your time and effort and investment … first,” said Mr. Roden-Reynolds, recommending the use of clothes and footwear treated with the pesticide permethrin.

“It’s the gold standard for preventing tick bites,” he said.

Tiny lone star tick larvae can crawl between the fibers of a sock, Mr. Roden-Reynolds said, but the permethrin will kill them on their way.

It’s also important to tuck in pant legs and shirt tails, he said, to limit ticks’ access to unprotected skin.

“Their instinct is to crawl upward,” Mr. Roden-Reynolds said.

He also urged people to check for ticks on their bodies and pets as a matter of routine whenever they’ve been outside.

Asked about tick-reducing landscape treatments, Mr. Roden-Reynolds was unenthusiastic.

“It’s usually the last-resort option I recommend,” he said. “We just want people to focus on personal protection.”

Mr. Roden-Reynolds also debunked the alleged tick-gobbling prowess of guinea fowl and wild turkeys.

“I don’t think at all they’re providing any biological control … of the tick population. There’s typically more ticks on them than in them,” he said.

Saturday’s symposium was moderated by Island Health Care physician Gerry Yukevich, and put on by the non-profit, Martha's Vineyard Hospital, Vineyard Medical Care, Dukes County Public Health Departments and the Fledgling Fund.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »