Fears of wildfire, concerns about trail safety and anger over this summer’s unannounced destruction of a homeless camp were the top themes when Islanders spoke to Massachusetts officials in charge of the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest on Thursday night.

More than two dozen people stood up in turn to address the 11-member delegation, led by Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation commissioner Brian Arrigo, during a public listening session at the Martha’s Vineyard Performing Arts Center in Oak Bluffs.

“It’s so critical for us who … make decisions on a statewide basis, to hear directly from the folks that are so impacted by our properties and so impacted by the policies that we put in place,” Mr. Arrigo said as the evening began.

His delegation got an earful over the next 90 minutes, hearing comments that reflected the many ways Islanders use and value the 5,300-acre preserve and also highlighted what Vineyarders felt was wrong with the DCR’s management.

Several speakers expressed outrage over the state’s clearing of the homeless camp in July, which drew an immediate outcry from Island leaders after tents, sleeping bags and personal property such as prescription medicines and family photographs were seized and disposed of as trash.

Naomi Higgins, a resident of the forest encampment before it was razed, told the state delegation that 22 people lost all their belongings that day, including two children.

“The people in the forest are electricians, mathematicians, nurses at hospitals and schools on this Island whose names I will not speak, because their anonymity is everything to them,” she told the officials.

“You took everything,” Ms. Higgins said, as the delegation listened silently.

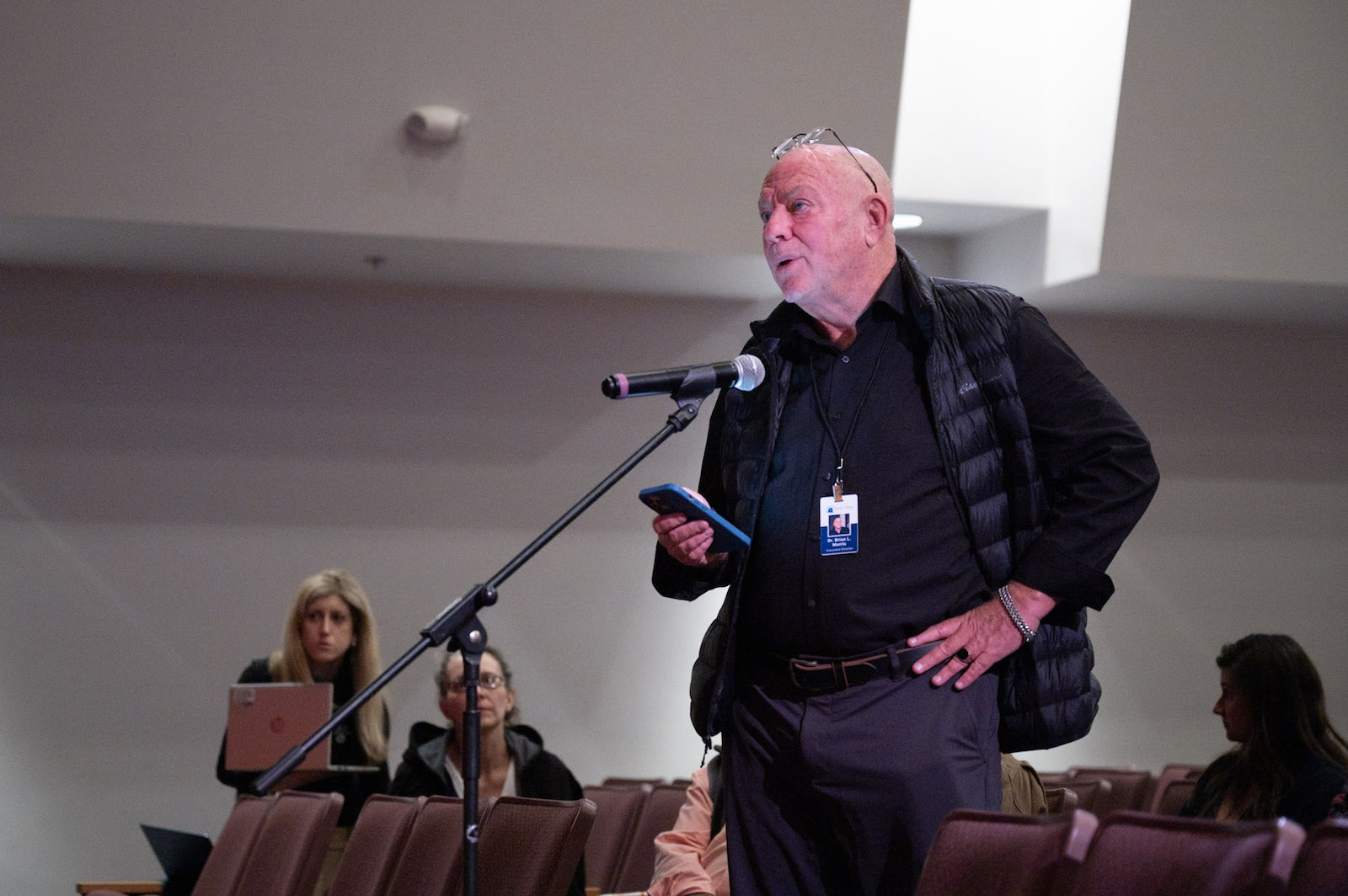

The state should have notified local agencies before the sweep, said Brian Morris, executive director of Harbor Homes, the Vineyard’s only homelessness prevention nonprofit.

“All we ask is that the next time DCR plans a clearing, please extend to us the courtesy of communication and maybe even collaboration, so that we can leverage our resources to proactively … minimize the disruption, loss of personal items and trauma to those who are already suffering,” Mr. Morris read, from a statement he’d prepared.

The DCR action derailed a public health outreach to the homeless camp, intended to offer tick-repellant treatment for tents and clothing, according to an official from another part of state government.

“What happened that day was inexcusable,” said Michael Hugo, director of strategy and government relations for the Massachusetts Association of Health Boards, who made a special trip to the Vineyard to testify on Thursday.

“We would have been able to have hands on and eyes on much of the homeless population, and may have come up with some homeless people that were unknown to Harbor Homes, and may have been able to extend some public health services to them,” he said.

Homelessness on Martha’s Vineyard is different from what’s seen in other Massachusetts cities and towns, said Mr. Hugo.

“Most of the people [living] in that forest have jobs. They have families [and] in the winter time, they live in houses that many people would be so envious that somebody even gets a chance to even go into. But those houses become Airbnbs during the summertime, and the people who are living there through the winter are displaced,” he told the state officials.

Mr. Hugo asked the DCR to notify town boards of health, as well as Harbor Homes, before it has another forest encampment cleared.

“There is a public health aspect to why these people are experiencing homelessness, and we take that very seriously,” he said.

Alexis Moreis, a council member with the Wampanoag Tribe of Chappaquiddick, also criticized the state’s response to the encampment of unhoused Islanders.

“Not only was DCR a guest on the land, but that is not how Wampanoag people treat our community members,” Ms. Moreis said.

“And so with that, in reaction, there should be outreach as well to the tribes about how anyone is going to be treated on these lands,” she said, calling for greater Wampanoag involvement in forest governance.

Several homeowners living on the forest’s periphery said they’re worried about wildfire and want to see more intervention by the state to keep their neighborhoods safe.

West Tisbury firefighter Granville White, whose home abuts the forest, said he sees the risk of flames spreading from dead trees leaning toward each other from both sides of the nearby bike path, which could touch off a widening blaze.

“It needs real foresters who know how to cut trees back and keep that barrier between the forest, which could burn, and all those properties which are so important to the taxpayer base of the town,” Mr. White said.

Chief Massachusetts fire warden Dave Celino said the current state policy focuses on maintaining buffer zones between forest and private land, so that local firefighters can control wildfires before they spread.

The state uses fire itself as one way to lower the risk, said Mr. Celino, who has more than two decades of experience with the Vineyard forest.

About 1,000 acres of the forest have been burned intentionally since 2012, he said, and over the past five years the state has trained 85 Island firefighters in wildland fire management.

Mr. Celino also noted that the state forest has a cooperative relationship with the U.S. Forest Service, which partners with the National Fire Protection Agency to promote fire-safe neighborhoods.

Homeowners concerned about their risks can request a fire safety assessment through their local fire department, Mr. Celino said.

“We’ve done 65 home assessments [on the Vineyard]. We’d love to double that, or triple that,” he said.

Alice Kyburg, of Skiff’s Lane in West Tisbury, expressed fear that a cooking fire in a homeless encampment could spark a catastrophic blaze.

“It needs addressing, or else I will be homeless … and a lot of other people will be homeless,” Ms. Kyburg said.

Speaking for the people who lived in the razed encampment, Ms. Higgins said fire safety was a priority.

“We had one fire pit, and we know how to handle fire,” Ms. Higgins said. “Our fire pit had a sand bucket next to it. It had the earth and the water ready to put out our small fire.”

Other speakers during the evening included bicyclists who want better maintenance of trail surfaces, equestrians suggesting more parking for horse trailers and several people who expressed concern about speeding electric bikes.

Suggestions that some of the state forest land be used for housing came from more than one speaker, but officials said it is designated as a forest preserve where housing and camping is not allowed.

Multiple Islanders called for the state to reopen the forest’s own house, formerly home to late forest superintendent John Varkonda and his family, so that the Vineyard can once again have a resident superintendent.

“It’s a great residence,” said Jane Varkonda, who lived there for 10 years before her husband’s unexpected death in 2014.

Since then, the house has been vacant; current superintendent Conor Laffey commutes from Falmouth, and Mr. Arrigo said state policies now make it difficult to provide employee housing.

“There are state ethics regulations and rules that we run up against.” the commissioner said.

“There are also some internal budget and administrative challenges around providing housing at a median rental income and and right now, we think that given the amount that we pay our employees, and the amount that the rent of the rent that would be charged, it would be a very difficult hurdle to overcome,” Mr. Arrigo said.

Following Thursday’s session, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation is taking written testimony about the state forest at mass.gov/forms/dcr-public-comments until October. 17.

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »