After more than two decades of living with Lyme disease, communities in the commonwealth are becoming fed up; many residents are finally saying, “We need something done now.”

Well, something is being done, much of it on the Vineyard. The Martha’s Vineyard Tick-Borne Disease Initiative is one of two promising initiatives against Lyme disease focused on the many things that people can do to reduce their risk.

The Vineyard initiative was established in 2010 with the generous support of the hospital local grants program. Under the direction of Michael Loberg and Matt Poole, with the all Island boards of health, a comprehensive program has been established. This includes enhancing diagnosis and reporting of cases, educating children, providing information via a superb website (MVBOH.org), as well as performing pilot studies of locally acceptable habitat management methods.

One critical goal is to present a set of recommendations to Island selectmen for reducing risk. The Vineyard initiative is now the state model for a community-based program of risk reduction. The only other such comprehensive program was based at the Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, but state funding for that program has disappeared, though it continues to offer tick management advice and education. The Cape Cod initiative is responsible for reducing the overall number of case reports from that area, largely by educating the public. We are sure that the Vineyard initiative will do the same here, and I urge everyone to bookmark the website, use it frequently and recommend it to others.

The other initiative is Gov. Deval Patrick’s special commission on Lyme disease, appointed as a result of legislation passed last year. Rep. David Linsky’s son contracted Lyme disease, with the result that he now is personally motivated to promote some actions for Massachusetts residents. The commission comprises members of the state Department of Public Health, scientists and representatives of Lyme disease support groups as well as those of boards of health.

Lyme incidence is increasing in much of Massachusetts, particularly in sites such as the route 128-495 corridor. This is a result of suburbanization and a reduced capacity to control deer herds. The Vineyard has been in an ecological equilibrium — no change in tick densities — over the last 10 to 15 years, reflecting the fact that it is one of the original sites for deer ticks and the pathogens that they transmit. (The agents of babesiosis — a malaria-like parasitic disease — and granulocytic ehrlichiosis — an infectious disease transmitted by ticks — were reported from Vineyard mice in 1938, indicating that these tick-borne infections were silently existing as part of the Vineyard landscape long before they afflicted people.) However, with increasing development and numbers of seasonal residents, there may be a concomitant increasing trend in reported cases of tick-borne infection. Action should have been taken 10 or 20 years ago to control deer ticks. Initiatives are now underway — better late than never.

Our mission is to compile a menu of recommendations with estimated costs and benefits so that priorities for state action may be formulated. Subcommissions have been formed for prevention, education, surveillance, funding (for intervention as well as research) and insurance and liability. This comprehensive effort mirrors that of the Vineyard initiative, but with a statewide focus.

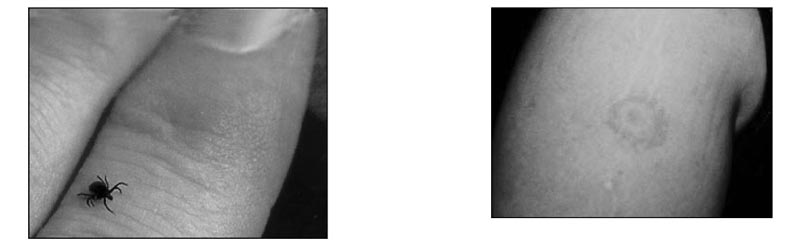

One of the messages that both initiatives are trying to promote is that there are many things that can be done now to reduce risk. Personal protection using any effective mosquito repellent on shoes, socks, feet, ankles and lower legs will certainly reduce the likelihood that a tick will find a person palatable. (Even better would be to treat clothing with permethrin or seek out and use commercially available treated socks and trousers, such as those made by Insect Shield.) Checking for ticks every night by feeling for new bumps will allow ticks to be quickly removed, which greatly reduces the risk of becoming infected, even if the tick itself is infected. Cleaning up around homes by eliminating brush and leaf litter within and near yards removes tick and mouse habitat. Yard perimeters may be sprayed with insecticide, preferably a granular pyrethroid (such as Bug B Gone Max). If applied as directed by the label, effects on the environment may be minimized. Above all, if everyone were to have any unexplained fever of more than two days checked out by a healthcare provider, we might be spared many severe cases of Lyme disease or any of the other tick-borne infections (babesiosis, granulocytic ehrlichiosis, deer tick virus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia). If detected early, virtually all of these infections may be treated successfully with no aftereffects.

I use the term risk reduction. We will never be able to eradicate (bring to zero) the deer tick or prevent all cases. However, public health objectives are relative; even reducing the number of cases by half is considered a tremendous success. Personal protection is a short-term approach. It requires constant attention and commitment as well as annually recurring expense and must be done forevermore. But just as important are long-term objectives. Let us restore the risk landscape to what it was 30 years or more ago. This means some uncomfortable decisions. Deer management is critical because dense deer ticks result from dense deer herds. Lands that are not hunted must be opened so that deer do not have sanctuary. We must find ways to let hunters more easily share the wealth of our lands. Habitat must be managed. The old pasture landscape did not have deer tick problems. It is unlikely that we will chop down the trees to return to such a landscape, but there are ways of cleaning up the forests so that ticks dry out from exposure to sun and wind.

Above all, we need education so that it is no longer a question or an extra thought: I need to wear this repellent, I need to check for ticks, I need to get this fever checked out, I need to clean up the brush around my home. For us to think this way as we do crossing a street (look both ways) is our long-term educational goal. However, we should not let our expectations dampen our optimism. Lyme disease did not appear overnight; it took 50 years of development, forest mismanagement and deer reproduction to promote it. It might take 10 years or more before we see any measurable reduction in case reports, if we are committed to action.

Individuals might disagree with some recommendations based on personal feelings or interpretations of the literature. I welcome debate, and encourage all to come help. If you disagree, though, be prepared to provide a constructive suggestion that might be considered in our quiver of arrows. Constructive means realistic, which is based on economics . . . who will pay, and can we justify the expense given all the other worthy public health issues?

But I hope that all of us would agree that it would be most gratifying to return the Vineyard to what it was like more than 30 years ago, when deer ticks and Lyme were rare, so that our children’s children won’t be faced with what we have today. This means a commitment at the community and individual level to do whatever it takes, using a mix of short-term and long-term approaches. We need to set aside as many objections as we can and just get to work.

Sam Telford is a professor in the department of biomedical sciences and Infectious Diseases at Tufts University. He has worked on the epidemiology of tick borne infections for 25 years,is a member of the Governor’s commission and advises the Martha’s Vineyard Tick-Borne Disease Initiative.

Comments

Comment policy »