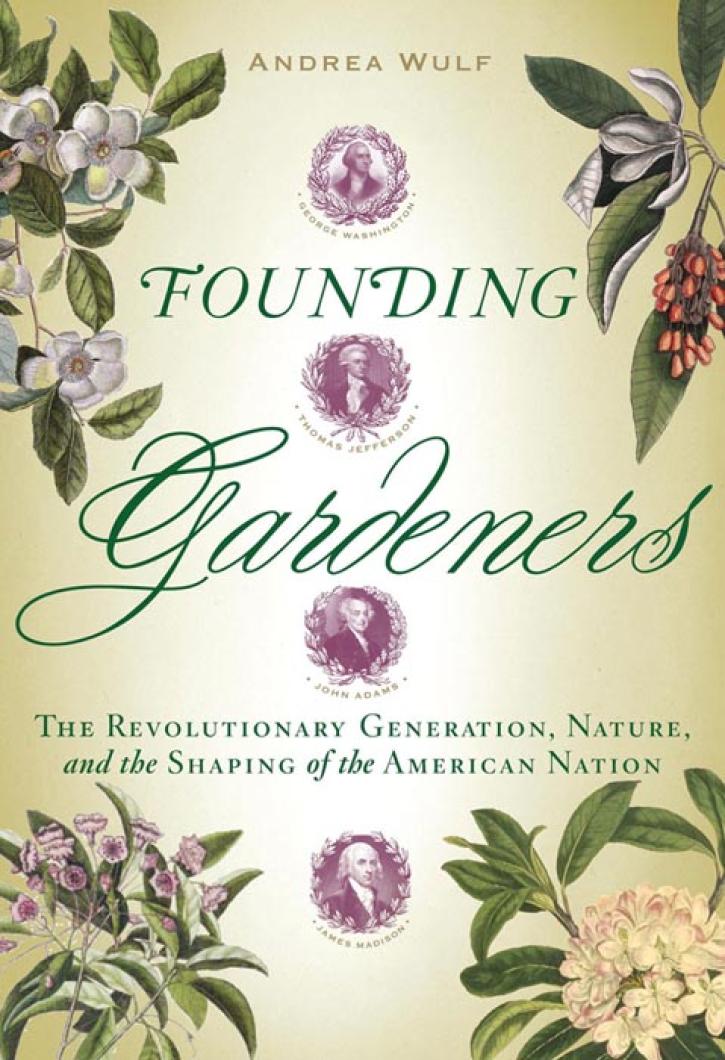

FOUNDING GARDENERS: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation. By Andrea Wulf. Knopf, March 29, 2011. 352 pages. $30, hardcover.

At first glance this book, with its lovely old-style sketches of such flowers as Rhododendron maximum and Kalmia angustifolia, gives you the notion it would make the ideal gift for someone who knows her forsythia from Scotch broom. But the moment you start reading Founding Gardeners by Andrea Wulf (Knopf, $30), you realize something groundbreaking is going on — pun intended.

This is a book that could get tea baggers and lefty grow-your-own-rhubarbers to join in a circle and admit, “We’ve all admired the founding fathers, but we somehow missed their most important message. Where did we go wrong and how can we get it right?”

Ms. Wulf, a Londoner, found her own ideas altered when some years back she took a road trip across the States from D.C. to San Francisco. She passed the hideous factories with their plumes of smoke, endless fields, and suburban homes with their impeccable little lawns mowed to within an inch of their lives. She wrote, “America exuded a confidence that seemed to be rooted in its power to harness nature to man’s will . . . whereas in England, everybody seems to be obsessed with their herbaceous borders and vegetable plots.”

Her opinion changed in 2006 when she visited Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello on a Virginia mountaintop. She saw cultivated vegetables, splashes of flowers, red maples, oaks, hickories and tulip poplars against the backdrop of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The exquisite natural beauty, both cultivated and wild, of Monticello stayed in her mind.

She discovered that the first four American presidents were assiduous gardeners, Washington with Mt. Vernon, Jefferson with Monticello, Madison with Montpelier and Adams constantly at work on his small but productive farm, Peacefield, near Quincy. But it was Benjamin Franklin who made the splashiest case for America to emerge as a nation of small farmers.

In 1769, Franklin listed the three ways by which a nation might acquire wealth: “The first is by War . . . This is Robbery. The second by Commerce which is generally Cheating. The Third by Agriculture, the only honest Way.”

Eleven years before the American Revolution, Britain legislated the infamous Stamp Act. Does anyone remember from their third grade social studies class what the heck this was? Ms. Wulf reminds us: It was a tax on all products derived from paper: newspapers, legal documents, liquor licenses, books and, this had to be the worst: decks of cards. And why were they doing this? They were flat broke from their exhaustive Seven Years’ War. An outbreak of anti-Stamp protests in America led to Franklin’s trip to England where, after a number of rejections from British officials, he argued his case before Parliament and succeeded in finally having the odious tax repealed.

More importantly, Franklin arrived at the conclusion that the Colonies could bring pressure to bear on the English by boycotting their goods. America, with its enormous resources of land, could be self-sufficient. He told the MPs, “I do not know a single article that the colonies couldn’t either do without or make themselves.”

Meanwhile seeds were sent in both directions across the high seas. Franklin was thrilled by an introduction to any new edible plant including a recipe from China called tofu! On both sides of the Atlantic, new cultivars were blended with established gardens.

Meanwhile, even after the Stamp Act was withdrawn, Britain remained adamant about prohibiting colonists from obtaining seats in Parliament. Franklin was dismissed from his official post in London. On his return to America, he believed more than ever that farmers held the key to America’s future. The other founding fathers were in total agreement. As Ms. Wulf writes, “It was the Constitution that welded them together politically, legally and economically, but it was nature that provided a transcendent feeling of nationhood.”

Doesn’t this sound fresh and new? Our own burgeoning belief in local produce, homegrown vegetables, the slow food movement and even amazing developments such as small, meticulous urban farms carved out of the ruins of inner-city Detroit: these are endeavors that would warm the cockles of Benjamin Franklin’s big heart.

In Founding Gardeners, Ms. Wulf makes us aware of the “seed boxes” that became the currency of long-distance friendships against the backdrop of looming hostilities. She spends serious time, concentration and loving attention to the founders’ country homes, each one an experiment in the bounty and agricultural possibilities of this new land. Each was a macrovision of a country of small farmers.

After the war, Jefferson and John Adams traveled to England for tours of stately gardens, many of them harboring trees and shrubs that originated in America. This agreeable surprise was the work of Philadelphia botanist John Bartram, who introduced more than 200 American species to the former motherland.

Earlier in Bartram’s career, delegates from the Constitutional Convention, in need of a break from wrangling over numbers of delegates to be instituted from each colony, visited the botanist’s plantation. There the conventioneers saw trees and shrubs from all 13 colonies grouped together and intertwined. The metaphor was not lost on them. They returned to Philadelphia and dispensed fair representation to all future states.

Ms. Wulf doesn’t shy away from the issue of slavery as the means employed by the South to establish lavish estates. Why plantation owners resisted digging in their pockets to pay salaries, with no restrictions on freedom attached, is a question worth posing in another book as well-researched and elegantly written as this one.

After James Madison retired from his term in office, he accepted a post as president of the Agricultural Society of Albermarle. In a brilliant but largely ignored speech, he urged countrymen to live off the land without destroying it. Not to pat ourselves too heartily on the back, but the Vineyard is one of those locales in America that has always honored these values and continues to preserve and expand on them.

Zucchini seeds, anyone?

Andrea Wulf will be speaking about Founding Gardeners and signing copies of her book, under the aegis of the Martha’s Vineyard Garden Club, on Saturday, May 28 at 4 p.m. at the Polly Hill Arboretum, at the Far Barn. Tickets are $10. For more information, call 508-693-9426 or log on to pollyhillarboretum.org.

Comments

Comment policy »