Editor’s Note: The following story was published in the Gazette on Jan. 18, 1985. William Bettencourt died on July 7 at the age of 87. A memorial service will be held on Saturday at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital chapel at 11 a.m.

BY HILARY STOUT

“For better than three generations the Down Town Club had been the major financial and political force in the city. It’s been said that more business was transacted over the small tables in the club dining room than in all of the commercial offices in the city and no one had the audacity or the insolence to run for mayor, for the city council, for the school committee or for any of the city’s seats in the Massachusetts legislature without gaining the blessing of the club.”

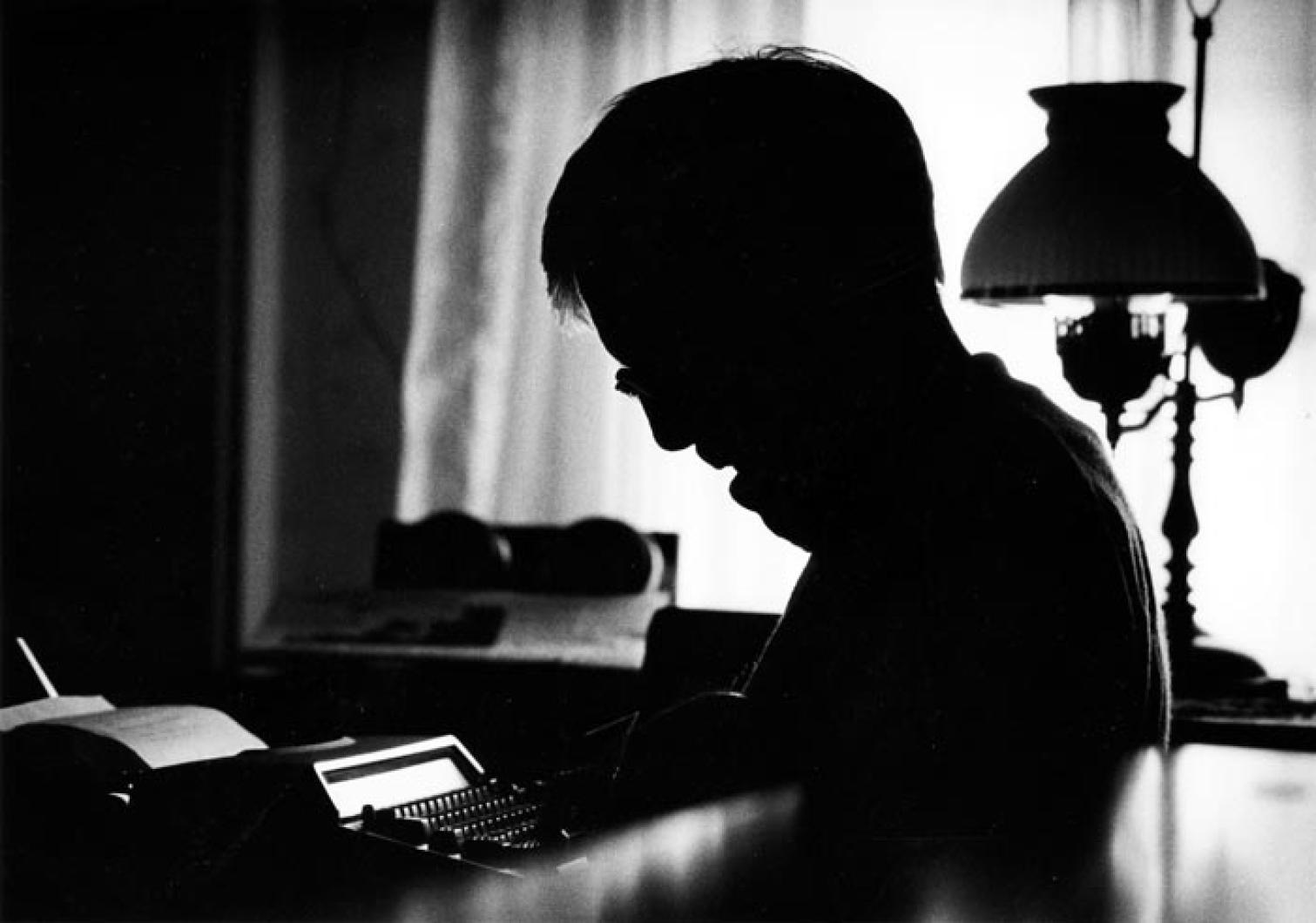

William Bettencourt, a 61-year-old, silver-haired man with a handsome face and a happy smile, wrote these words two decades ago, on a heavy, black manual typewriter, one painful tap at a time.

Mr. Bettencourt — Billy to everyone who knows him — was born with cerebral palsy, an injury of the brain which weakens the muscles and limbs.

The words are the opening lines to his first novel, which he finished several years ago, still typing with one crooked finger, one letter at a time.

The Homemade Loaf by William Bettencourt now sits in a plastic bag of several hundred loose and yellowed onion skin pages in the author’s closet off the living room of a white-shingled cottage in Oak Bluffs.

A year ago he showed it to a friend who liked it and retyped a hundred of its pages and sent it off to three of the largest New York publishing houses.

None of the three — not Simon and Schuster nor Alfred Knopf nor Random House — accepted the manuscript.

But Random House returned the novel with a note which encouraged the author to keep sending it out, and told him his work was “publishable.”

So Billy Bettencourt and Barbara Seward of West Tisbury, the young friend he calls his “agent,” are going to do exactly that.

In the meantime, Billy Bettencourt continues to write.

He does it nearly every day, now on an electric typewriter, but still one strained letter at a time, still for hours at a stretch, and still with joy.

“A midsummer heat wave held the city in its grip. For days a hot sun blazed down from a cloudless sky, burning everything, once lush and green, until it resembled straw. The usual afternoon breeze had already come up off of the Atlantic but as it crossed the land that lay between the city and the sea it lost its cooling effect. And only those lucky enough to be up on the hill, high above the city, even noticed a change in the air.”

He likes to put his typewriter (he can lift it himself if he works at it) on a painted TV dinner tray with metal legs in the warm living room of the home he shares with his sister, Helen McGrath. He likes to sit in front of it in a black rocking chair and place a stack of clean typing paper on the green-carpeted floor at his side.

Mr. Bettencourt’s ailment makes it difficult for him to speak, but when he tells of why he writes, certain words — like “love,” like “satisfying,” like “fun” — ring out clearly in his voice, spoken with difficulty in hoarse and stuttered tones.

Mr. Bettencourt is working on a second and a third novel. One is a sequel to his first — his tale about George Murphy, a strong-willed Irish-American who lost a leg when a coal truck ran over it, a story with love, with sex, with business, with politics, all the stuff of life, including death.

Each day he spins his tales a little further. On the good days, when his imagination is running strong and his fingers are feeling spry, he can finish two pages.

If his imagination is racing faster than his hands will move, his work goes a little slower.

If he forgets some of his thoughts while he’s transferring others into letters, he gets a little “frustrated.” But he keeps writing.

Sometimes he types so late into the night that his sister has to yell down from her bedroom, “That’s enough for tonight, Hemingway!”

If Phil Donahue has a good show, or he doesn’t have much in his head, he takes a break, or maybe even forgets about writing for a day. But most days he writes, and many days he writes all day.

“I don’t get tired of it.”

“The crowd that gathered in and in front of George Murphy’s bakery was a rough, rowdy, unruly gang who were certain that they had the answers to the important questions of the day. They ranged in age from men in their forties to men in their sixties. George told them, in words and looks, that he could do without them. But still they congregated. There were the McManns, Micky with the cane and Micky with the pipe, Albert Muggsy Hogan, Eddy Prunes McHoney, Pat Rafferity, Joe (the mouth) Kelly, Mack Monahan, Officer Bill Clancy and the noblest Yankee of them all, Will (the snortin’) Norton.”

Billy Bettencourt was born on Martha’s Vineyard. He lived in Taunton with his family for several decades and later returned to the Island with his mother.

When he was 25, Mr. Bettencourt learned to walk. A series of operations straightened out his feet and knees, and with a pulley and weight set rigged by his father, he worked to strengthen his body.

When his mother died in 1980, Mrs. McGrath, a nurse at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, moved into the little, green-shuttered Oak Bluffs home to care for her brother.

Mr. Bettencourt never went to school. “In our day they didn’t have education for people with cerebral palsy as they do today,” Mrs. McGrath explains.

But Billy learned from his mother and his sister, and he learned from reading. He loves to read, he says, and he used to read “everything,” but now he doesn’t as much because he spends his time writing instead.

But he still reads the newspaper every day. On summer mornings he rides into town on his three-wheeled bicycle to buy it. Winter days a home nurse brings it to him.

Every once in awhile Mr. Bettencourt’s sister tells him he should “write what you know, write about yourself.” But Mr. Bettencourt shakes his head “no.”

He says he’d be bored. He says he’d rather make up stories. That’s what he likes about writing — “storytelling.”

In fact he doesn’t think he’s all that good a writer, but, he knows, “I can do a story.”

What he wants now is for someone to take his story and to help him with the writing and editing. So he can publish it.

He wants to publish the novel very much. “You dream about those things,” he says. “But you never think they’re there.”

“Those wartime summers were not much fun. The boys were all in the service and the girls sat around talking about what they were going to do when the boys came home. The Harpers had stopped coming up, it was just too dull for them, but Lucille came to spend a few days each summer with Abby, Maud, and Osca. Even Maggie and Jean enjoyed her visit as Maggie was not displeased to give up her place at the bridge table while Lucille was there.

“When Maggie was leaving after that second summer of the war she had a feeling that she would never come here again.”

“But dreams do come true,” he says in scratchy cadence, and this time his words and his belief are clearly understood.

Comments

Comment policy »