Alligators like to eat marshmallows, although they shouldn’t. Alligators also like to eat turtles because they are crunchy outside, but soft and chewy inside. Clearly, alligators have good taste and undoubtedly, 50 years ago when Alley’s General Store carried penny candy, alligators would have been in seventh heaven there. Alligators are not, however, voracious eaters — their large mouths and fierce bite notwithstanding, they can get along quite nicely eating just once a month.

I learned all this as I strolled on a walkway a few feet above dozens of alligators at Summerdale, Alabama’s Alligator Alley, just outside of Mobile, recently. Below me — sometimes snoozing, sometimes looking cross and scrappy, were dozens of alligators in a spring-fed cypress swamp. I had imagined, and rather looked forward to meandering directly among the alligators. I had thought that could be quite exciting. But as it turned out, not only was I above them, but there were railings along the walkway to keep visitors from falling below into the swamp. There, other denizens included bullfrogs, water moccasins, ribbon and brown water snakes. Of course I know that water moccasins are dangerous. I don’t think bullfrogs are and I don’t know anything about ribbon and brown snakes, but I was glad, after all, that I wasn’t mucking about within water moccasin reach even if the alligators had had their fill.

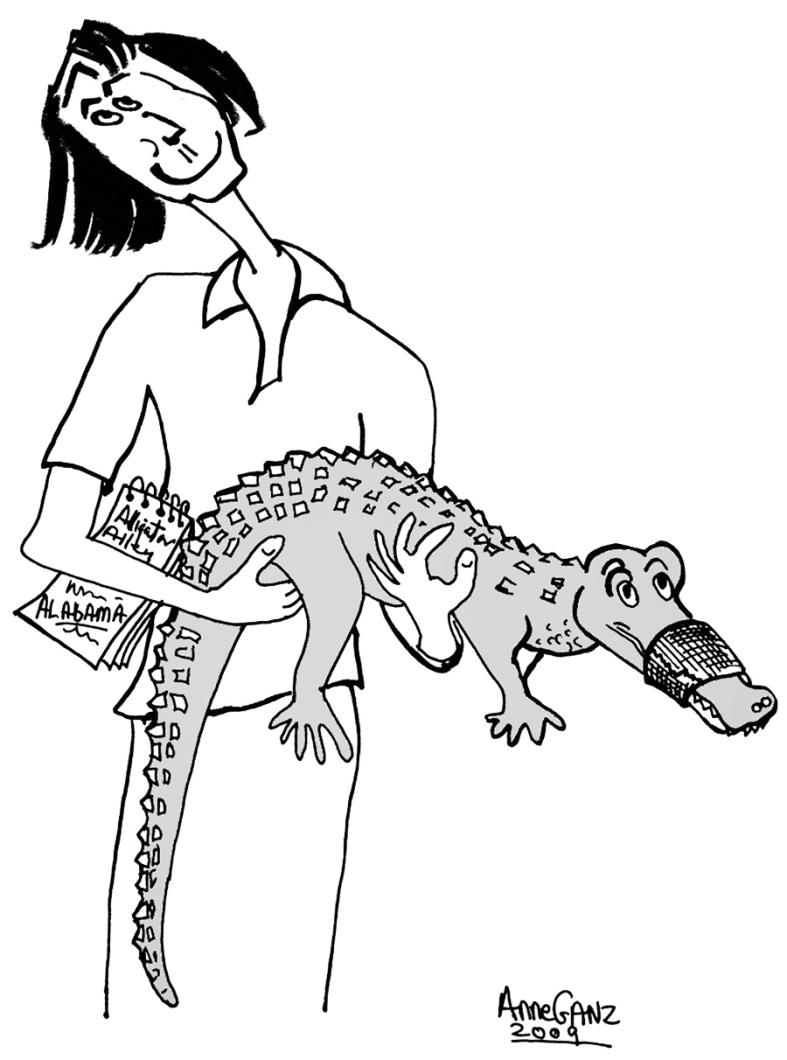

Although alligators can be found in South Carolina, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Georgia, by far the largest concentration of them — between 35,000 and 50,000 slither about in the swamps and bayous of Mobile and Baldwin counties in Alabama. When I heard that, and was invited to visit Alabama and go on an alligator walk, I couldn’t have been happier. I remembered how disappointed I had been as a child when a neighbor where I lived in Brooklyn, N.Y., had a baby alligator that escaped his pen and went wandering somewhere on East 26th street. No neighborhood children were allowed into their backyards until he had been found. There was even one policeman who searched for him in the grass in our backyard. I remember looking out the window watching him, hoping the baby alligator would be hiding somewhere in our grass and I could see him. I don’t remember now whether he was ever found or simply escaped into a sewer and lived there happily ever after. But if he had been found, I wouldn’t have been allowed to touch him, of course, but a highlight of Alligator Alley was holding a baby gator in my arms.

Admittedly, his mouth was duct-taped shut just in case he got cross — or hungry — but holding him was a thrill all the same. I cannot say that he was cuddly, but his skin was soft under his front legs and he made no effort to get away. Even though his mouth was taped, however, I did not attempt to scratch him on top of his tapered nose. Alligators, I was firmly told, once they bite, put on more pressure per square inch than any other creature except, perhaps, a great white shark. (Memories of Jaws went through my head.)

I had seen crocodiles in Africa, lounging on river banks and for awhile there were some in a pond outside the presidential palace in the Ivory Coast, and I saw them peering greedily up at passersby. I did know that one of the differences between alligators and crocs is the nose shape. Alligators’ noses are tapered; crocodiles have pointed noses. I don’t know if crocodiles eat more voraciously than alligators. I have always thought that crocodiles were on the alert to snap at anything that came in sight. Alligators — if they are well fed — are much more laid back. (It is unwise, however, to count on that and approach one in a friendly way.) But the Alligator Alley alligators even have pet names. There is Mighty Max and R.J., Crunch and the Colonel, Fat Albert and Old Stumpy, who has only three legs. Losing a leg for an alligator in captivity is sort of like stubbing a toe, Wesley Moore, who owns Alligator Alley and all its reptile residents, said matter-of-factly. There is little risk of infection for an alligator because of the antibodies alligators have. They also have blood that clots quickly. Old Stumpy, because he lives in the alley and is fed there, manages quite nicely with just three legs. Were he in the wild, however, where he had to find his own food, capture and drown it, it might be a different story. I also learned that alligators have been around since the days of dinosaurs and haven’t changed much in their appearance and that they can live as long as 80 years. I found out, too, that mating alligators bellow while baby alligators make a meow-like sound.

The nesting season for an alligator is in late spring and early summer. Then the female makes her nest on a mound of dirt and leaves, often disturbing a nest of fire ants in the process. Thankfully, an alligator is tough-skinned enough not to mind getting stung, although the ants may eat the eggs.

It takes about a month for the eggs to hatch and the babies that emerge have brown and yellow stripes. They don’t turn olive green until, between the ages of four and six, they become teenagers. In the 1930s and 1940s, alligator skin shoes and handbags were in vogue and alligators had to be put on the endangered species list since they were being so ruthlessly hunted. But by 1985, they were plentiful again and are no longer considered endangered. Indeed, at the end of my trek in Alligator Alley, I had a bite of charcoal-grilled alligator tail that was tender and quite tasty.

Alligator Alley got its start in 1937 when Wes Moore’s grandfather had a vegetable farm where the alley is now. He grew sweet corn and cabbage and turnips. He dug a channel to drain his fields of water so his crops would grow better. But beavers liked the channel and would swim it and build their dams, causing the fields to flood, especially at times when there were six or eight inches of rain. That happens sometimes in Mobile, the rainiest city in the country. So in the 1960s, to save his farm, Wesley’s grandfather bought an alligator to eat the beavers.

Old Joe the Alligator did a fine job of it, but one day all the beavers were gone and Wesley’s grandfather had forgotten to feed Old Joe. Old Joe, who was used to being hand-fed and clearly was hungry, went after Granddaddy and chased him right up to his truck. Wesley was with his grandfather, enjoying every moment of the adventure. Then and there, Wes, who was a little boy, decided if he and his Granddaddy escaped Old Joe, he was going to raise alligators. And so in 2004 he began collecting them. He hires licensed alligator hunters to go after them for him with tranquilizer darts. Once the gators have been stunned, the hunters tie their mouths up tight enough so they can be safely transported to Alligator Alley by truck.

My walk along the boardwalk above the alligators was interesting and informative, but as I’ve said, a little less exciting than I had imagined. In the end, though, I was just as glad, for I learned that once an alligator has caught his prey, he rolls underwater with it to drown it and, after it’s dead, leaves it to soften up and season under a log. Alligators have tremendous bite, but smooth teeth that aren’t good for chewing anything tough. I had imagined alligators snapping hungrily at me as I walked by, and that wasn’t the case. The alligators I saw all seemed pretty full of frog or chicken or marshmallow or nutria dinners. Nutria are big rat-like creatures that have become a nuisance in Alabama wetlands and alligators please everyone by gulping them down.

I know rats not infrequently nest in Island barns and wander out sometimes to explore homes beyond the barns. Of course T.J. Hegarty, our county rodent control officer, does his best to keep them in check At first, learning about the alligator’s efficacy in doing in nutria, it ran through my head that one or two alligators-in-residence might be just the ticket to help out T.J. But then I remembered all the trouble we have had since the alleged importation of skunks a few decades ago. I guess even if alligators could thrive in our New England climate, I would just as soon not have any lounging on the State Beach in summer. The prospect of wind turbines in the distance, once they come, will be intrusion enough.

Comments

Comment policy »