Mussels don’t taste like duck, but the difference between the flavor of farmed mussels and wild ones is like the difference between a domesticated duck and one born to the pond. The meat of a farm-raised duck is tenderer, milder and tamer — while a wild fowl is more toothsome, nuttier and gamier, admittedly not for everyone.

And so it is with mussels. Farm-raised mussels from Canada, which are what we almost always get these days at Vineyard fish markets and restaurants, are plumper and softer textured than their wild Island cousins, and their taste is sweeter and gentler — delicious in its own way.

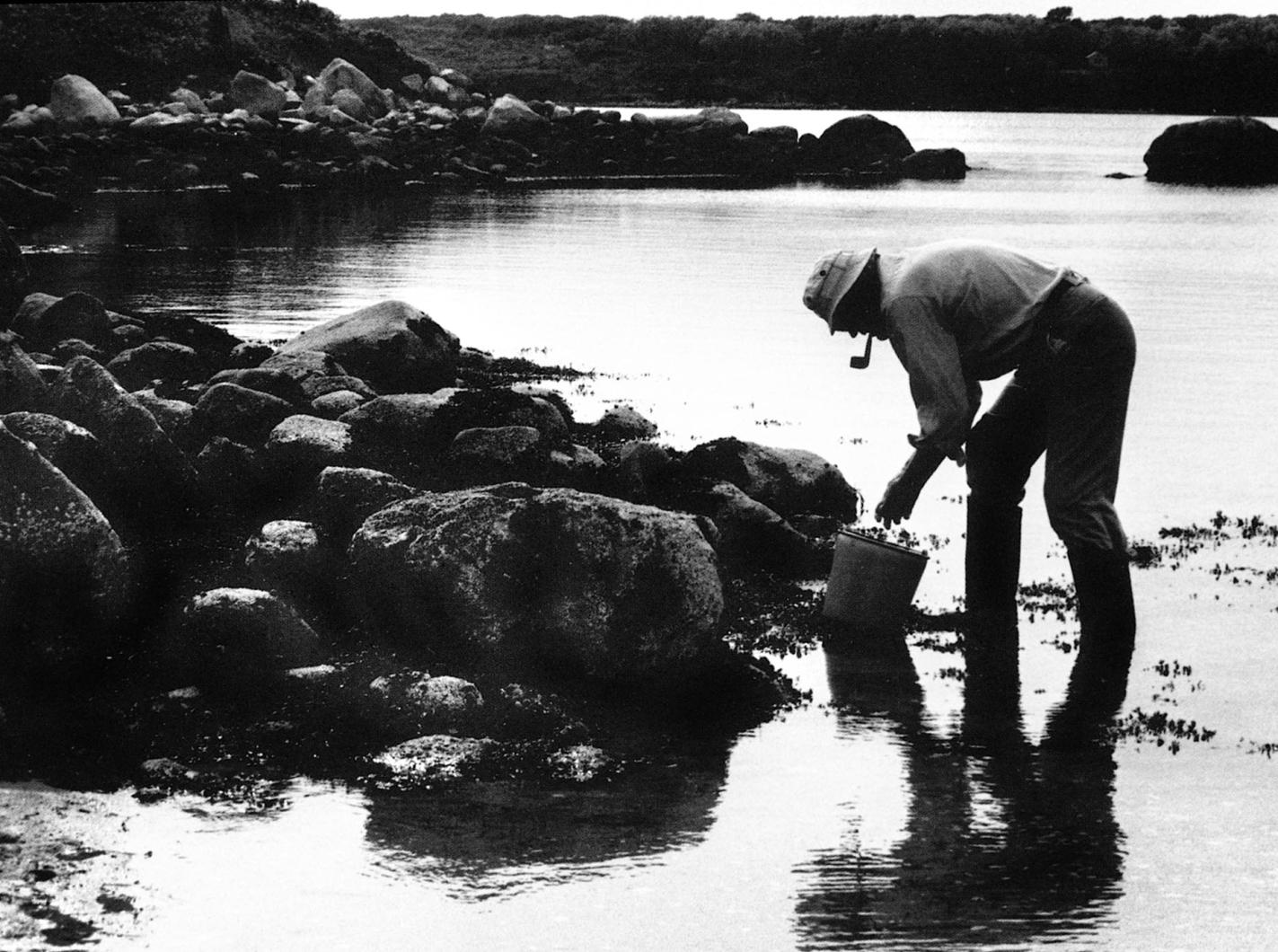

But there is something uniquely appealing about the unruly flavor of wild mussels that one gathers at the beach, scouring the shallows of the intertidal zone along the Vineyard’s north shore, searching beneath the nutrient-rich seaweeds that swaddle the shellfish, keeping them moist when the tide strays out too far, and lending them an intensity of both taste and nutrition.

These wild gathered mussels possess a richer, tangier, almost biting flavor compared with the farmed, a wholesome chewiness to the meat and an invigorating near-medicinal potency to the broth, like a warm tonic. And they sometimes contain surprises rarely found in domesticated varieties, an occasional crunchy miniscule crab — or, more rarely, a small imperfect pearl, mottled white and black.

These distinctions between the wild and the domestic are not confined to mussels, or ducks, but echo up and down our food chain — from the bland mealy flesh of pen-raised fish compared with the firm texture and the depth of flavor of a bass or bluefish that one plucks from the ocean only hours before supper, to the cranberries that come frozen in plastic bags rather than directly from an Island bog, or limp salad greens shipped from California versus crisp wild water cress harvested beside a local stream.

This is not to say that domesticated food is all bad. A little convenience goes a long way in life, and these store bought items — fish, berries, greens and more are often quite delicious. But we risk losing something more than merely flavor by constantly succumbing to the temptations of domesticated food.

We risk the lack of that experience, the loss of time spent foraging for our meals in fields or along the shore, time spent outdoors — in the case of mussels, wandering along the Island’s edge in rubber boots or bare feet, seeing who inhabits the tide pools and feeling the sensation of wind, sun and sand against our skin. Surely this is more enthralling than a grocery store

We risk losing the culinary inspiration and the true appreciation of our food that comes from gathering and handling what we are about to eat — the intimate tactile contact derived from debearding and scrubbing mussels, gutting and filleting a fish or simply washing still damp soil from just gathered greens.

And we risk losing an appreciation for the seasons, and for the rhythms of life.

It is not practical, and perhaps not even desirable, that we should each gather or grow all that we eat. It is fine to let someone else harvest our oysters and lobsters or produce some of our vegetables, just as it is acceptable, even preferable, to let a mechanic fix our car or occasionally pay a trained chef to prepare us a special meal. The division of labor has made possible the sum of human civilization, both the detriments and the rewards; we have come this far — and, for better or worse, turning back seems most unlikely.

But we don’t have to surrender entirely to the dictates of our bittersweet collective enterprise. Sometimes even a small act of culinary rebellion, like breaking the daily routine and heading to the shore to gather supper, reminds us of the basics, of where life really comes from, and where it ultimately must go.

•

Like most simple recipes, the one that follows — for mussels and pasta in broth — is a suggested guideline with infinite variations. The recipe calls for fresh herbs, shallots and cream for flavor, but after making this once the combinations can be altered at will — try ginger, basil and coconut milk; curry, mint and cream; or chopped tomatoes, garlic parsley and white wine. These dishes can be made with either wild gathered or store bought farmed mussels — or sample both and decide which you prefer.

Mussels In Broth With Pasta, Shallots And Cream

Serves four

4 lbs mussels

1 lb. spaghetti or angel hair pasta

1 ½ teaspoons minced shallots

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

¾ cup cream

a couple twists of freshly ground black pepper

Scrub and debeard the mussels and rinse them quickly under cold running water. Farmed mussels will hardly need any attention at all while wild ones will require a few more minutes of work. Wild mussels have stronger and more pronounced filaments — or beards — that hold them to the rocks while the tide surges in and out. The beards are removed with a simple up and down tugging motion.

Bring 6 quarts of water to boil in one pot for the pasta. Place the minced shallots, chopped parsley, ¼ cup of water and the washed mussels in another pot and turn to high. Drop the pasta in the boiling water and drain when still slightly chewy, after about nine minutes. Allow the mussels to cook, stirring occasionally with a large spoon, until they all open completely, which will take about as l ong as the pasta. Turn the heat off under the mussels and pour the cream into the broth and add a little fresh black pepper.

Portion the pasta and mussels in four large bowls — there will be enough left over for extra helpings — and ladle a cup of creamy broth into each bowl.

Serve with crusty French bread or garlic bread, and everyone will be happy and full.

Comments

Comment policy »