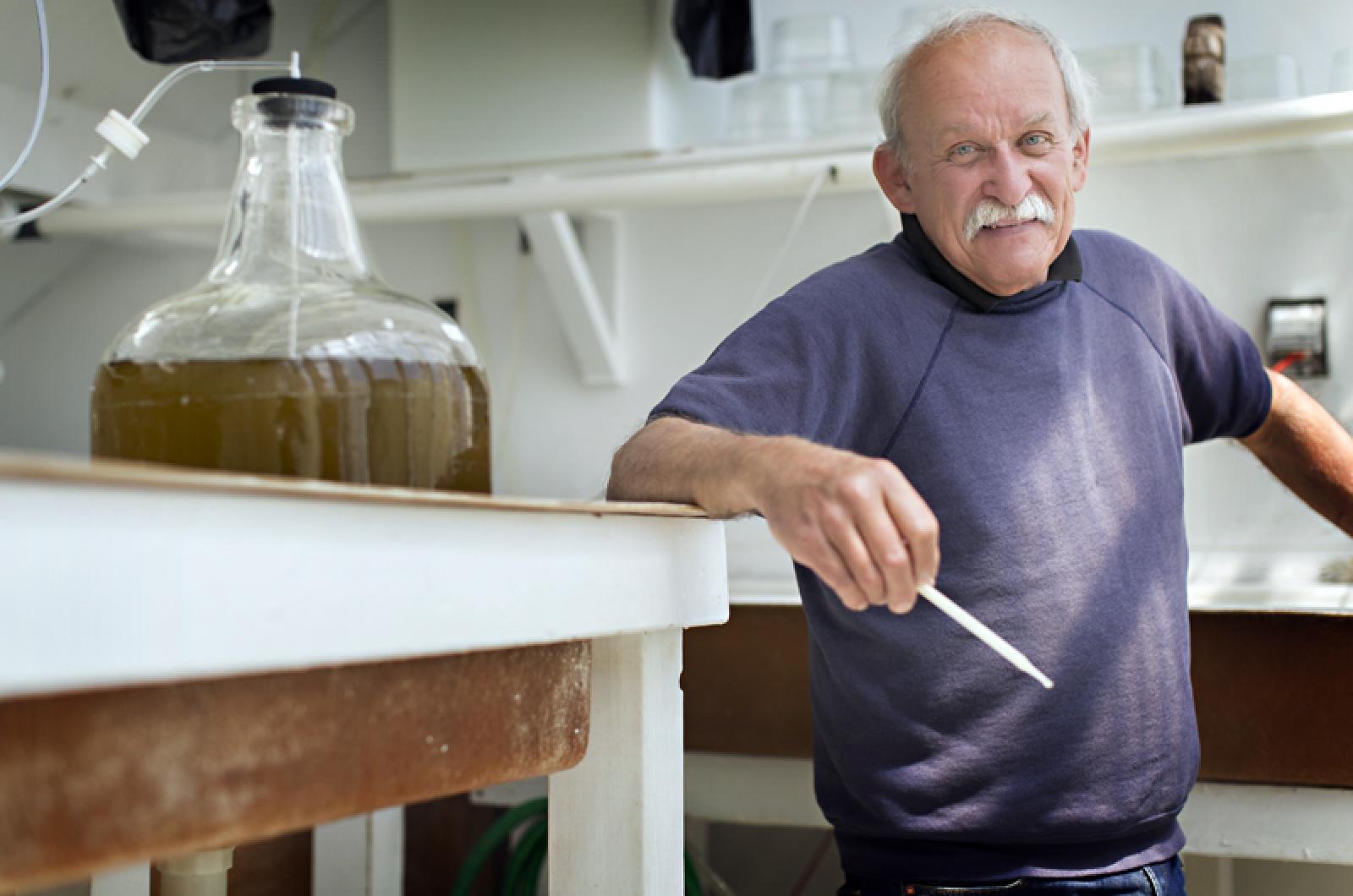

On a brisk late April morning, Rick Karney stands at a large sink filled with warm water and 24 Pyrex glass meatloaf dishes filled with filtered salt water and quahaugs. The shells are labeled CH, EDG, VH and OB in black Sharpie, indicating what pond and town each clam hails from. As executive director of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group, Rick is at the leading edge of ongoing work to keep the Island’s abundant shellfish population healthy and productive.

Two months ago, four of the Island’s six shellfish constables collected the quahaugs for him.

A few weeks after the quahaug delivery, Rick and his team began “conditioning” the 43 hard shell clams that the constables had collected. “Kind of like a spa treatment,” Rick explains. “We slowly bring the water temperature up while feeding them a rich diet, which includes several varieties of phytoplankton (microscopic algae). This fools them into thinking it is spring and, hopefully, makes them feel ready to spawn.”

He looks down and sees a clam release a stream of white eggs.

“I have a female!” he yells.

Then another clam in another dish sprays a milky white cloud.

“And a male!”

With a long dropper, he collects some of the sperm and puts it in the water with the clam that has just laid her eggs.

“They are so old,” he says. “From the Cambrian age [roughly 510 to 600 million years ago]. They are Zen, they have no faces left, no heads, just the important stuff to eat and reproduce.” Watching the clams spawn, the phrase primordial ooze does come to mind.

Rick continues: “There is no way to identify a clam’s sex until we do this. So we collect a bunch and, surprisingly, the split between males and females is always fairly even. We’ll see what happens this year. Each female produces about one million eggs.”

Amandine Surier, hatchery manager and fundraising coordinator for the shellfish group, chimes in. “We collect clams from six places to promote biodiversity,” she says. “In this mix of clams this year is a brown variety of faster growing clams, which we introduced about 35 years ago to support the commercial fisherman, clams with purple shells for the jewelers, and the native white clams, which have original genetic material and other important biological markers such as disease resistance.”

The hatchery, tucked into a hillside on the western edge of the Lagoon Pond on the Vineyard Haven side, was built in 1980. The building is essentially three large rooms stacked on top of each other. The bottom floor has two giant holding tanks for filtered sea water. The second floor has a large square shallow sink, a shower area with racks of frames for clams, scallops and oysters to grow on, a small desk area cordoned off by a shower curtain (so the microscope doesn’t get wet) and a small room for refrigerating and caring for what Rick calls the “starter culture for the algae.” The third floor of the hatchery contains giant glass and plastic tanks full of brown and bright green algae — food for the young shellfish. There are also four bigger tanks for growing newly spawned animals and a long sink. Rick, Amandine and Emma Green-Beach, special projects manager and education coordinator for the group, stand at the sink observing the quahaugs.

Rick hands Amandine the dropper and asks her to empty the water out of the sink and continue spreading sperm around. “The sperm gets both the males and females going,” he explains.

Rick did not set out to become an advocate and breeder of filter feeding bivalves. He grew up in Bound Brook, N.J., a place not known for its clean water or air.

“It was the age of better living through chemistry,” he says. “There were factories all around us. My grandfather and one of my uncles worked at an asbestos plant in Manville, N.J. Half a mile away from our house there was this giant American Cyanamid factory that would release these giant clouds of toxic smoke that would burn your lungs. Bakelite, now Union Carbide, was there. Factories were all around us. When we’d be driving around, I knew where we were geographically by the smell in the air. Part of the reason why I do this is that I watched the destruction of Bound Brook, which was right by my house.”

Rick’s father was a layout machinist — a person who transfers blueprint designs into metal forms and prototypes. His mother worked for a company that made transistors and then worked for Johnson & Johnson in their packaging department. Rick attended Rutgers University and got a degree in biology. “So I could go to graduate school,” he says.

In February of 1973, he got a job at the Institute of Marine Science program at a field station in Wachapreague, Va. Three years later, he received a call from Michael Wild, the coastal planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, asking him if he’d like to come to Martha’s Vineyard and help provide technical assistance for the shellfish constables. A year later, they were building the first pilot hatchery on Lagoon Pond, which was essentially a shack on a steep hill with a dock. Then in 1980, Rick and the group raised $100,000 to build the nation’s first solar shellfish hatchery, where he still works today.

“With a few improvements,” he adds. “We had linoleum that essentially rotted from all the water. Now we have this really cool poured plastic floor.”

He goes outside to show off the new dock and a swimming pool pump they use to bring water into the hatchery. “There has been a big decline in the water quality here,” he says. “You see that layer of black muck at the edge of the Lagoon. That is from too much nitrogen from the groundwater. This nitrogen fertilizes both the microscopic algae and the bigger bottom growing seaweeds. So we have an overabundance of the phytoplankton and seaweed. The bottom growing seaweed gets very thick and dies back and settles to the bottom and creates this black mud. This area becomes both anaerobic and acidic. That much acidity will dissolve the shells of young clams. It is expensive, but we have to address the nitrogen issue.” In the original hut-like hatchery, where he checks on Emma’s gold-lipped mussel breeding project, he recalls the early days of the program. “Really, anybody in his right mind would have walked away,” he laughs. “But I didn’t.”

As a kind of cosmic joke, as Rick shows off the hatchery’s improvements, Emma and senior hatchery assistant Chris Edwards discover that two of the four larval conicals — 400-liter tanks of warmed filtered water that will hold the spawned clams — are leaking. After inspecting the two tanks, Rick prescribes the cure: “Well, we’re going to have to drain the one with the crack, put some Marine-tex on it and then fill it back up. I think tank two has a broken valve. But, again, we won’t know until we take it off so we have to drain this one too.” Hatchery crew members grab yards of clear plastic hosing and get to work. Rick appears relaxed. “Basically, we’re running a MASH unit here,” he says.

He heads back upstairs to check on the quahaugs. More males are doing their thing but no more females have revealed themselves. Amandine suggests they do a count to see how many fertilized eggs they have. Rick begins a fairly elaborate sequence of straining the eggs out of the water, concentrating them, and then adding more water to dilute them so that he can begin to calculate a rough estimate of how many they’ve harvested. Then he swishes eggs and water from one white bucket to another.

“This may seem random, but it is actually a surprisingly accurate way to count the eggs.” He drops a bit of the water with eggs onto a slide and brings it over to the microscope. “It’s been about two hours since we last looked. Now you can see clusters of cells have formed.”

Peering into the microscope, he explains the evolution of the bivalve at hand. “With a quahaug, within hours there is a blastula, a cluster of cells. By tomorrow evening they will be trochophores, which is essentially marine larva that can swim because they have cilia,” he says. “Then they grow a shell and they will be veligers because they develop a swimming organ that looks like a foot with cilia. This is the same cilia that catches their food. Finally, they will grow a foot, which is just a small muscle, and become pediveligers. After about a week or two and metamorphasize into juvenile clams. Adult clams are about three years of age. You can tell a clam’s age just by counting the rings on its shell.”

The dissertation over, with the help of a simple counting machine that he clicks with his left hand, he begins to count the eggs. When done, he pulls out an old-fashioned pocket calculator and types in a few numbers. He smiles. “So far we have 22 and a half million eggs. Probably enough. Not the best. But not bad.”

He reports the numbers to Amandine. The two have been working together for 14 years and their dynamic often feels like an old married couple.

“We are each other’s longest relationship,” Amandine says.

“I had all these applications for the job from these amazing PhDs from India and beyond, writing to me saying, Dear most noble sir,” Rick recalls.

“I was not like that,” Amandine says. “I did not send that kind of letter.”

“Nope. And that is why we imported you from Paris.”

“And I lived on his property for three years,” Amandine says. “Rick has the most incredible garden. That is his other love. But if you think about it, it makes sense. He is a biologist.”

“Growing things is my thing,” Rick says.

“We all have gardens,” Amandine adds. Emma pipes in: “I am going to grow everything for my wedding in 2016.” “In fact, when we interview people, we always ask them if they have a garden,” Amandine says. “You have to have an inclination to nurture life to work here.”

An hour and a half later, the tanks for the fertilized eggs have been repaired and Rick checks on the clams again. “No more females.” He decides to use three of the four tanks and that this will be the end of the spawning for the day. He goes through another bucket swishing process to divide all the fertilized eggs equally between three tanks.

“I used to be so neurotic about everything,” he says. “I wouldn’t let anyone eat in here. I would measure everything to the T. But then I learned things like a little bacteria in the water is actually like a probiotic for the clams. We use an iodine solution to disinfect, but it is not perfect and that is a good thing. One year I used an ultraviolet light to sterilize the water and nearly killed all the animals. Now look at this place. I let them keep yogurt in the refrigerator with the algae, grow tomatoes in the window upstairs near the algae.”

Danielle Ewart, the Tisbury shellfish constable, stops by. She is checking on how the Vineyard Haven clams have done today. Rick reports that they have done well. They discuss the recent oil spill in Lake Tashmoo and when Rick thinks the shellfish will be ready for their nursery beds. After Danielle leaves, Rick brings the three buckets of equally distributed egg water upstairs to the tanks and pours them in.

“Amandine is now in charge of growing all the algae here,” he says. “She’s really got it down. I used to be crazy uptight about the formulations, but she has a sense for it. We grow several kinds to feed the quahaugs — a high lipid strain of phytoplankton that actually have the same omega 3s that are good for us. We also grow an Isochrysis, which is good for larvae. It likes high temps. And then there’s an algae that smells so sweet when it gets warm that I want to make a cologne out of it. That’s the Chaetoceros.”

The conversation then turns to the 15 quahaugs that have not done anything yet. They will keep them in the conditioning tank — a garbage barrel with warm water and food — until this batch of clams is a bit further along.

“As a kind of insurance if something really goes wrong,” Rick says.

Fortunately, in his time, he has had few complete disasters. “Hurricane Bob was tough. We lost power for a week. That was stressful for both me and the animals. But they are tough. Tomorrow we’ll feed them in the afternoon and we’ll see. From here on out, until Columbus Day, the hatchery is like an orchestra playing a symphony. Today was the first movement. Soon, this whole place . . .” he gestures, “will be filled with life. And so will the other two hatcheries.” The shellfish group also manages the former state lobster hatchery on the Lagoon and a summer hatchery on Chappaquiddick.

With that, Rick and his crew spend about 45 minutes cleaning up. He makes notes in his logbook recording the temperatures in each of the three incubation tanks. “I’m 64,” he says. “Someday I’m going to have to leave. Maybe I’ll do some more aquaculture consulting. But this place is my baby. Somebody has to keep these guys in line.”

For now, he will close up, head to Cronig’s to get a salad and then home to watch some Jon Stewart where he’ll probably fall asleep in his recliner. And tomorrow morning, he’ll be back to feed the clams.

Special note: The annual fundraiser for the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group is this Saturday at the Chilmark Community Center from 6 to 10 p.m. Johnny Hoy and the Bluefish will perform.

Richard C. (Rick) Karney

Profession: Shellfish biologist and director of the Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group Inc.

Age: 64

Born and raised: Bound Brook, N.J.

Moved to Martha’s Vineyard: 1976

Family: “My mother Sonya is 91 and still lives alone in Bound Brook, New Jersey. Fortunately, my sister in law, Carol, lives nearby and checks in on her.”

Pets: Goldfish. “I have a pond. They are pretty big. The herons keep the population at about 30.”

Favorite time to eat shellfish: “The fall. The quahaugs, scallops and oysters are all storing up fat for the winter. The cool water makes them almost crisp.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »