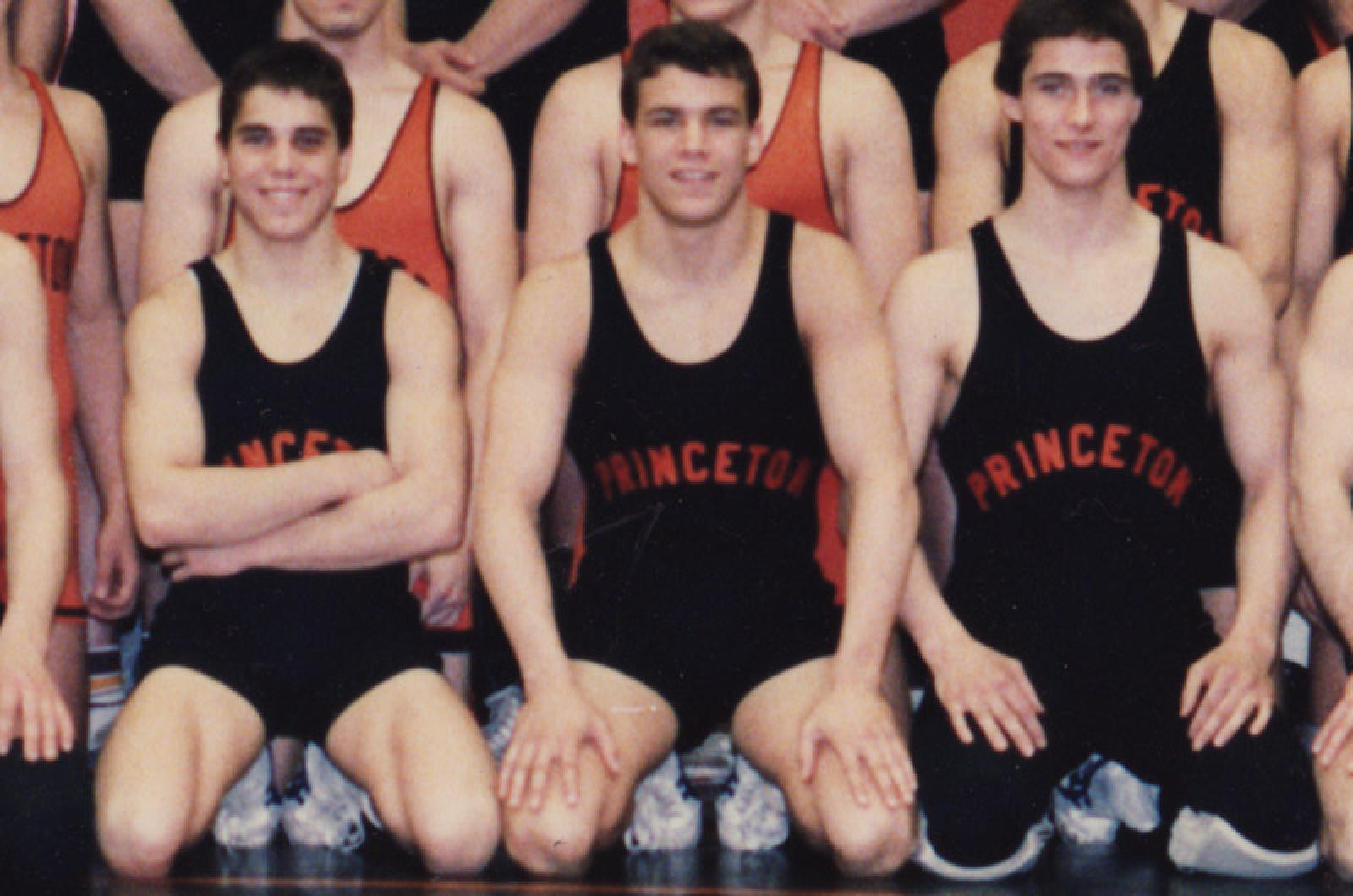

I was one of three boys growing up. We didn’t own dolls, we blew up G.I. Joes with firecrackers. We ate a lot of meat, compared scars, had pushup contests and wrestled competitively at school, in the basement, up and down the stairs and in the backyard on warm summer nights.

My brothers and I embraced our mom like a den mother trying to tame a pack of wolves. It was an impossible job and we knew that and so loved her even more because she fed us, clothed us and hardly ever broke down, at least not in front of us.

As for my father, he was one of us until he fell hard for Olivia Newton-John, her sad Australian yearning wafting through the house a concrete sign that he had mellowed, his manhood blown away by a high speed hair dryer. We countered with Led Zeppelin, the Stones and AC/DC.

But that was a long time ago. Today Taylor Swift is singing that she’s feeling 22, I have an American Girl doll in my lap and my fingernails are painted a lovely shade of violet.

I have a daughter. She is seven years old. We call her Pickle.

In recent years I have spent many hours backstage fixing fairy wings, have had my lips glossed weekly, been asked whether my colors are fall or summer (definitely summer), and been told I should be more like regular daddies.

“What do you mean?” I asked, while pounding out a set of pushups.

“Like daddies who play dolls without doing exercises at the same time,” Pickle said.

“Trust me, we are all like this,” I said. “Some just hide it better than others. Now hop on my back. I need some more weight for these pushups to feel a good muscle burn.”

•

Today, however, is a special day. Today we are headed off-Island for a gymnastics meet. This is a first for us, this journey of father and little girl into the maw of competition, traveling to some far away town where other little girls in pigtails and glitter stand in the way of our quest for gymnastics domination and blue ribbons.

“Daddy, it’s not like that,” Pickle says as I try to take her through the finer points of the hard stare and tough guy walk. She is dressed in a purple leotard and practicing her one-handed cartwheel. “Remember, people we don’t know are just friends we haven’t met yet.”

“Oh yeah,” I say. “I keep forgetting that part. Could you at least growl for me? Just once?”

Pickle growls and then blows me a kiss. I shrug and we head to the car. I carry with me a bag of stuffed animals which I cover the back seat with to “chase away the butterflies” in Pickle’s stomach. I also have three Taylor Swift albums and a bag of snacks. We pick up her friend Maeve and mom Caitlin and the four of us head to the ferry blasting T. Swift, singing out loud and pumping the air with our fists.

Losing him was blue, like I’d never known, missing him was dark grey, all alone . . . . but loving him was red, burning red.

•

Even though Taylor Swift is a long way from AC/DC, ( she had the sightless eyes, telling me no lies, knockin’ me out with those American thighs), it doesn’t take long before I am living in two worlds, the one happening right now and the one I inhabited as a child. With my son this feeling is a daily one as I too was once a little boy, but with my daughter it is more rare as our childhood worlds do not intersect nearly as much. But suddenly I am in the passenger seat and my father is driving, the two of us on the road together nearly every Saturday and Sunday as he took me to off-season wrestling matches up and down the entire state of New Jersey.

We rolled a bit differently then. Our trips were mostly intense affairs where dad wasn’t even allowed to stop for coffee because I would be cutting weight, seated next to him encased in sweats and a plastic suit, maybe even spitting into a cup trying to squeeze out the last 1/4 pound before weigh-ins.

There was no psych up music and definitely no stuffed animals or coloring books. And I wasn’t thinking about making friends, sitting there silently cursing some kid I had never met for making me lose weight, and planning quick and decisive revenge on the mat.

And yet there we were, not much different really, a parent and child heading out into the world as we drove down unfamiliar highways, discovering new towns and far flung high schools.

My dad didn’t know much about wrestling and I liked that about him, this inability to give me too much advice. He was my chauffeur, like all parents become, but once the meet started he was also my corner man shouting only wide open encouragement. During the regular season it would be coach in the corner, but there were no coaches allowed in the off-season and I can still see my father standing on the edge of the mat, the quiet guy around the house suddenly transformed and yelling as loud as he could: “Atta boy Billy, atta boy.”

In between periods he would towel me off, wiping the sweat from my forehead and shoulders, our bodies closer and more intimate than at any other time. And at the end of each match, after the referee had raised my hand into the air, I would walk slowly over to him so I could take in the full range of his smile and hear him say, “good job son, good job.”

No such luck at a gymnastics meet.

At a gymnastics meet, I soon discover, the parents are sent to a small room off to the side while the kids go through another door reserved for participants and coaches. In the other room the little girls braid their hair, take sips from their water bottles and get last-minute advice from their coaches. Perhaps they even make friends like Pickle had hoped. I have no idea because I had my face pressed against a window looking out into an empty gym waiting to see my girl emerge again. The window was filled with parents’ faces, mostly moms but a few dads too. The guy next to me sounded like he was whimpering and I thought about asking him for a hug.

Eventually the parents are herded from the small room into the gym. We all find spots in the bleachers. It is a holiday meet and the warm-up music is appropriately themed. John Lennon’s So This Is Christmas comes on as all the girls enter the gym. There are perhaps 100 kids out there on the mat testing the springy floor, the balance beam, bars and the vault. Older kids are wading into the stands and selling gym-o-grams, where you wish your child good luck on a notecard and it is read over the loud speaker. I buy five, a few under assumed names such as “Mr. Bench Press says stay tough Pickle,” hoping she’ll hear it and look over at me in the stands.

But it is a one-way street, just me looking out at her and an odd feeling overtakes me as I watch her every move from my perch. I realize how I am always watching her, that is my role as her father, but now I am part of a crowd in an anonymous sea of parents. It is a distant feeling, one that creeps up my spine and lands with a lump in my throat the size of the ferry boat.

I begin waving frantically at her and calling her name. Finally she looks over at me and gives me a small, quick wave as if to say, “Please calm down you old fool.”

And with that I can finally sit back down, comfortable in the knowledge that she knows where I am and also that I know nothing of this sport and can only yell wide open encouragement: “Atta girl Pickle, atta girl.” But, oh how I wish I could rise from the bleachers and be her corner man.

•

Later on, after the meet is over and we are headed home, we are both quiet in the car and it occurs to me that I have no recollection of the rides home during my youth. Perhaps my father and I were mostly silent too, tired and content to just reflect on the day’s events. It is a good feeling and I can’t stop glancing at Pickle in the rear view mirror, seated in her car seat, her ribbons in one hand and her security blanket in the other. She is at once a very little girl and growing older with each mile we travel. And it strikes me how I too am growing older and younger at the same time, one of the byproducts of parenting I never saw coming. I am both a father and a son, consistently led back in time by my children to the boy I once was.

“Hey Pickle,” I say.

“Yes, Dad?”

“How about we stop by and visit your grandfather on the way home?”

“What for?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I just want to say hi.”

Comments (29)

Comments

Comment policy »