A Los Angeles movie company is currently casting actors for a film that will chronicle the story of the late Sen. Edward (Ted) Kennedy and the accident on Chappaquiddick in which a young campaign worker was killed.

Apex Entertainment, which has shepherded big-budget films including Secretariat and Miracle, plans to begin production in the next few months. A company spokesman said the producers would like to shoot part of the film in Massachusetts, but have not yet made a decision about locations.

“I’ve done a lot of true life stories, many sports stories, but this one had a deep impact on this country,” Mark Ciardi, president of Apex Entertainment told the trade magazine Hollywood Reporter on Dec. 14. “Everyone has an idea of what happened on Chappaquiddick, and this strings together the events in a compelling and emotional way. You’ll see what [Senator Ted Kennedy] had to go through.”

Mr. Ciardi did not return a call from the Gazette by deadline.

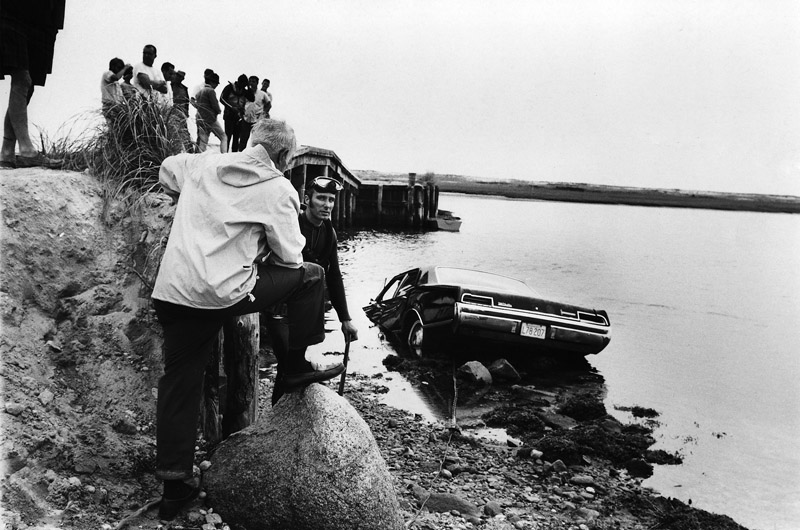

On July 18, 1969, Senator Kennedy drove his car off the Dike Bridge, then a narrow wooden structure with no side railings, after leaving a party. A young campaign worker, Mary Jo Kopechne, was a passenger in the car and died after the vehicle plunged into the water. Senator Kennedy did not report the incident to police for 10 hours, and later pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident. He was sentenced to two months in jail, but the sentence was suspended and he served no jail time.

The accident made international headlines, became fodder for Senator Kennedy’s political foes, and remains a hot subject for conspiracy theorists.

In past years, some Chappaquiddick residents have resented the intrusion of news media and curious tourists, as well as the association of their home with the accident. But encroachment on the small island across the Edgartown harbor has waned as time passed.

“It certainly has quieted down in the 25 years I’ve been out here,” said Chris Kennedy (no relation to Senator Kennedy), the Martha’s Vineyard superintendent for The Trustees of Reservations who lives on Chappaquiddick. “We used to have 100 vehicles a day that would travel down to Dike Bridge just to take photos. Young people don’t really know about the saga of Ted Kennedy and Chappaquiddick. It doesn’t seem to be the burning interest.”

The film is in the final stage of the development phase, but several Chappaquiddick residents contacted for this story were not aware of the project.

Chris Kennedy predicted if the company does try to shoot on location near the Dike Bridge, it will find plenty of opposition.

“There will be some real push back,” he said. “They would have to sign agreements for liability and security. It’s a whole procedure.”

But not everyone is unhappy about the prospect of a Chappaquiddick film.

“I think it would be interesting,” said Leslie Leland, former owner of Leslie’s Drugstore in Vineyard Haven, who was the foreman of the Dukes County superior court grand jury which investigated the incident. “Believe me, people are still interested in it. It’s fascinating stuff. The Kennedy stuff is always fascinating. It would be good for the Island.”

The film has attracted plenty of attention in the film industry. Sam Taylor-Johnson, who directed Fifty Shades of Grey, is slated to direct the Chappaquiddick movie. The script by screenwriters Taylor Allen and Andrew Logan was named to the 2015 Black List, a well-regarded list of film projects favored by industry insiders.

The Black List describes the film as “a historically factual look at what really happened when Ted Kennedy drove off the road into a Martha’s Vineyard bay with Mary Jo Kopechne in the car.”

The production company has not contacted the Edgartown selectmen or The Trustees of Reservations seeking permission to film on the Vineyard. The town owns the bridge and a parking lot, while the Trustees own the causeway that leads to the barrier beach. Joseph E. Sollitto Jr., clerk of the Dukes County Superior Court, said no one has contacted the court recently for records of the legal proceedings.

Mr. Sollitto was in the courtroom in Edgartown on the day Senator Kennedy pleaded guilty. A law school student working summers and weekends as an Oak Bluffs police officer, Mr. Sollitto was often called on to provide security at the courthouse. He was quite surprised when the senator’s wife, Joan Kennedy, entered the courtroom and took one of the few remaining empty seats, right next to him.

In the storage room just off his courthouse office, Mr. Sollitto pulled down an unabridged dictionary-sized book, the original transcript of the inquest into Ms. Kopechne’s death. It was first impounded by the court, but later made public.

“We still sell the transcripts today,” Mr. Sollitto said. “It’s $100 if you want it here. If we have to mail it, it’s $120.”

He remembers a mob of reporters gathered in downtown Edgartown, but initially, year-round Vineyarders didn’t show much interest, he said.

“I don’t know that a lot of them paid that much attention to it at the time,” Mr. Sollitto said. “It was an accident, somebody was found in a car drowned. I don’t think anyone saw the ramifications. It was a piece of history. It cost him the presidency. He probably would have been president.”

Mr. Leland was elected foreman of the grand jury months before the tragedy at the Dike Bridge. When prosecutors declined to convene the grand jury, Mr. Leland called it into session himself. A judge ruled that the grand jury could not see the impounded inquest documents, and could not subpoena witnesses questioned during the inquest. The grand jury did not return an indictment. To this day, Mr. Leland is frustrated at the legal process.

“We were shut down,” he said in a phone interview from his winter home in Florida. “We were sworn to secrecy for life. I didn’t dare say anything when it came out. I didn’t dare speak out.”

Mr. Leland’s insistence on an independent grand jury investigation earned him enemies.

“There were threats made on my life and my family,” Mr. Leland said. “I had received the threats by phone and also by mail. It was not very pleasant. I had state police protection 24 hours a day, for a month.”

Stephen Kurkjian was a young reporter with The Boston Globe and beginning his fourth year attending law school at night, when he got a call from an editor telling him to get to Chappaquiddick fast. He was staying at his family’s summer cottage in Plymouth.

“I had always presumed he sent me because I had this legal background,” Mr. Kurkjian said. “It was absolutely not the truth. He sent me because I was closest.”

Mr. Kurkjian went to work tracking down the medical examiner, knocking on doors near the Dike Bridge, and dogging the district attorney in charge of the proceedings. He was waiting outside the courthouse for Senator Kennedy to appear before the Hon. James A. Boyle when he pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident. He said the high drama and political consequences were a seismic event, like nothing he had ever seen.

“Every day it became more and more of a circus,” Mr. Kurkjian said. “The day, Friday, that he agreed to plead guilty, it was a true circus. The town went about its way. The crowd in front of the courthouse that day were tourists and newspapermen. The townsfolk were proudly proper. They weren’t gawking at us.”

Islanders may have been proper, but they cast a skeptical eye on the spectacle surrounding the scandal. When Judge Boyle convened the inquest in January 1970, reporters once again descended on the Island. The Vineyard Gazette made special note of the apparel of the press corps.

“The newsmen gathered on the scene early Monday morning in the crackly cold for the long wait until 10 o’clock when the inquest was begun, a motley crew if ever there was one in their assortment of winter raiment,” the Gazette reported. “Some of the television people looked like a group of aging boys prepared to go sledding in light blue windbreakers and stocking caps with pompoms. One male photographer cut a dashing figure in a mid-length black fur coat and a matching fur hat. Jayne Brumley, who covers politics for Newsweek, was there in a maxicoat of uncompromising fire-engine-red. The columnist, Mary McGrory, stood swathed to the nose in a scarf, in a kind of New England Jashmak. John Fenton, appropriate to a gentleman from the [New York] Times, wore earmuffs of a conservative navy blue. The mass of reporters, photographers, and cameramen had become a juggling band of red-faced-foot-stompers and hand-rubbers.”

Some people mark Chappaquiddick as the point when Martha’s Vineyard transitioned from a farming and fishing community with a few summer visitors to a tourist destination known all over the world.

“When Chappaquiddick happened, the world knew where Martha’s Vineyard was,” Mr. Leland said.

“That put the Vineyard on the map,” Mr. Sollitto said. “Nobody came here, usually everybody went to Nantucket.”

Comments (33)

Comments

Comment policy »