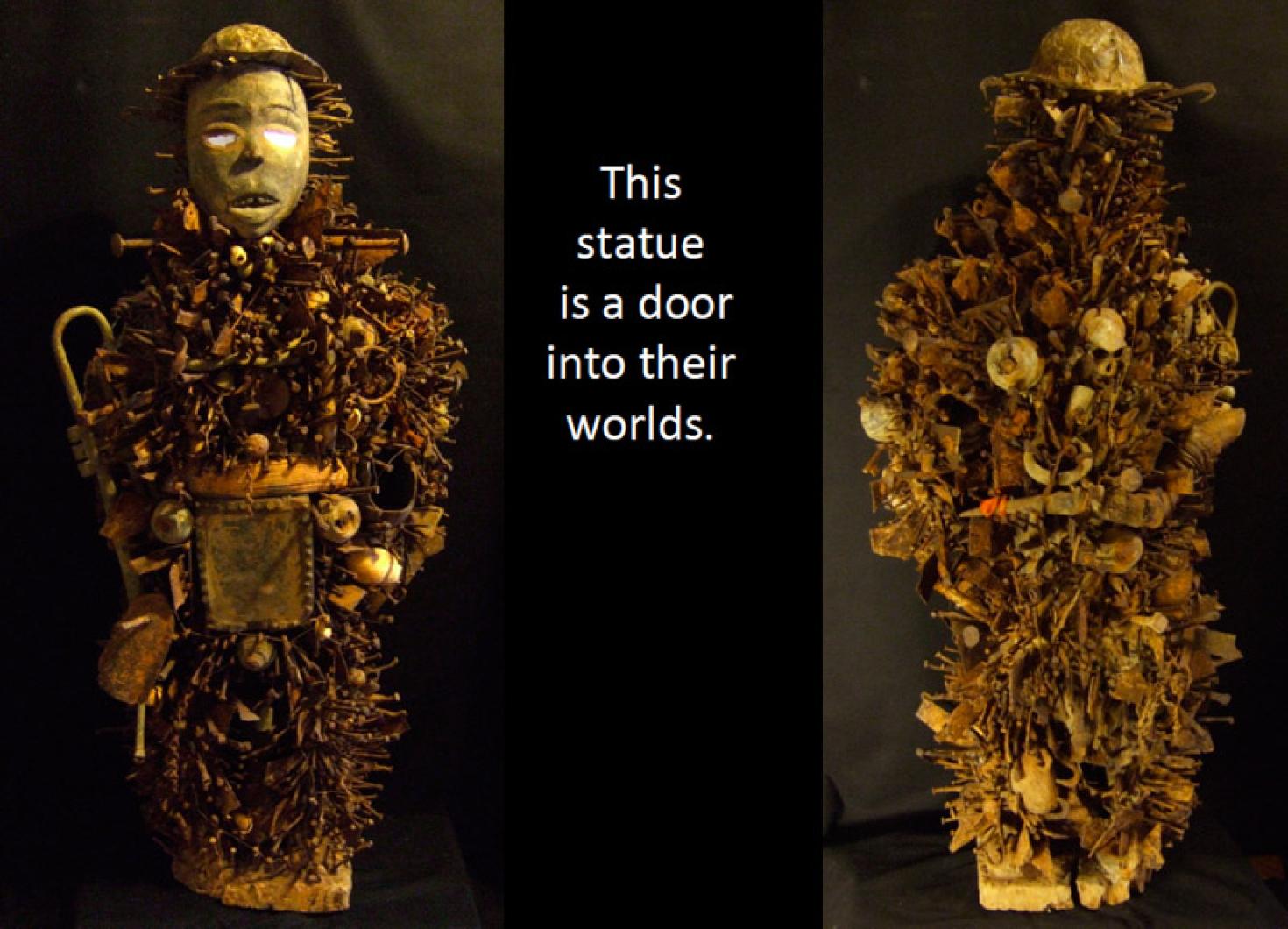

His shell-shocked eyes seem to look clear through to another world. And if he could talk, the stories he could tell might fill a library. He wears a facsimile of a metal doughboy’s helmet from World War I and carries a trumpet of the kind used by American band members who crossed the sea to fight on the Western Front. His entire body from head to toe is pierced through and adorned with more than 1,000 objects, each one a unique window into the past.

The BaKongo statue, known as a n’kondi (pl. minkondi), was recently on the Island, where renowned prehistorian Duncan Caldwell of Aquinnah and colleagues pored over its many features, which include likely grenades, the regulatory knob from a German lantern and other artifacts associated with World War I.

“I’m always interested in loose ends,” said Mr. Caldwell, who spoke about the statue last week as part of the African-American Literature and Culture Festival at the Oak Bluffs Public Library. The talk coincided with an exhibit of assemblages, books and other works by the late surrealist, jazz poet and trumpeter Ted Joans (a close friend of the Caldwells), whose work was partly influenced by the type of statue Mr. Caldwell has been studying for years.

What sparked Mr. Caldwell’s interest in the statue many years ago was an encounter with a friend and former arms collector who identified the grenades as typical of the first six months of World War I. “And then I realized,” he said with characteristic enthusiasm, “I had to answer how on earth grenades got onto the statue.”

A small group of visitors at the library followed Mr. Caldwell on a two-hour journey that covered centuries of Congolese history, including the trauma and transformation of World War I, which brought many Africans and black Americans together for the first time and set the stage for Congo’s independence in 1960 and a greater struggle for civil rights at home.

“This statue is a door into their worlds and into the trauma of that conflict,” Mr. Caldwell said of the many BaKongo soldiers who fought in Cameroon, Tanganyika and Europe. “The only problem is that it’s a door with many, many keys.”

He described a cosmology based on metaphors of water, and a world where humans interact with local spirits known as minkisi. Each n’kondi had a small box or “charge” (often covered in glass to represent the surface of water and the interface of dimensions) that contained the necessary ingredients to link the desired spirit to the object. Mr. Caldwell has broken new ground by describing not only the activating ingredients, or medicines — but what he called activating structures, which he said depicted the Congolese cosmology itself. In some cases, the structures involve a circle with perpendicular bars meeting in the middle, with the horizontal bar again representing the surface of water and a bridge between worlds.

Minkondi were used in their communities to retaliate, forge alliances or otherwise attract the attention of the resident spirit. Activating the statue required physically piercing it with spikes, or adorning it with special objects. That task was handled by a nganga, a sort of middleman between the client and the spirit. A n’kondi might accumulate hundreds or thousands of attachments, including, in some cases, other minkondi.

Many have argued that the practice emerged only after European contact and the arrival of images of Christ on the cross or Saint Sebastian riddled with arrows. But Mr. Caldwell believes the BaKongo were using wooden spikes long before then. He noted that unlike the image of nails in western art, piercing a n’kondi was regarded as an act not of injury, but of activation. (Some of the works by Ted Joans incorporate nails and tacks, echoing the image of the n’kondi.)

Many of the statues that did cross the sea were first stripped of their activating charges and castrated.

“It wasn’t the statue that was significant to them, but the activating charges,” Mr. Caldwell said.

The Magic Trumpeter (its true name is unknown) is somewhat unique in that it has all of its charges (and genitalia) intact, and that it incorporates such a wide variety of objects, many directly associated with World War I. Every object tells a story, Mr. Caldwell said, although many of the stories may never be told. He speculated that even the long stare, made all the more haunting by the application of reflective material on the eyes, was a depiction of the shell shock many soldiers experienced in battle.

The objects create a dense thicket covering every square inch of the statue’s body. They include hooks, bolts, spikes, padlocks, bells, horns, a hippopotamus tusk, cowrie shells, tree snails, bones, teeth and glass. Mr. Caldwell noted the importance of padlocks in the slave trade, during which they were often traded for humans in the Congo.The many spikes were likely taken from a railway that Joseph Conrad observed while in the Congo and later wrote about in Heart of Darkness.

The attachments may seem disorganized at first glance, but Mr. Caldwell has found structure in their arrangement. A complex wire network, for example, may have been used to link objects from the same person or a succession of ngangas. Or they may have depicted additional cosmograms. The VMFA may eventually X-ray the entire statue for greater detail.

“Because it has all of its charges, all of its bilongo, it is, I think, the most complicated work of African art that anyone’s ever had to analyze,” Mr. Caldwell said. “And I’ve barely scratched the surface.”

“And even when the statue is fully scanned and mapped, we will still have barely scratched the surface,” he added, “because every one of those pieces of hardware had significance and a story attached to it, and the people who knew those stories have died. If we can get 0.5 per cent of the significance out of it — that was originally a part of it — I’d feel really, really lucky.”

Still, what he has learned so far is enough to spark the imagination.

He said the statue points to an early alliance between African and black American cultures at a critical turning point in world history. He drew attention to the brass trumpet secured to the statue’s side like a rifle. A logo and serial number reveal that it was manufactured by Buegeleisen & Jacobson in Manhattan around the turn of the century. It probably belonged to one of the musicians in the 27 African-American military bands that served in Europe during the war, Mr. Caldwell said.

One regiment, known as the Harlem Hell Fighters, fought in a part of the Western Front with so many African troops that the area in France became known as l’Afrique. (The regiment’s bandleader, Lieut. James Reese Europe, was a leading figure in the African-American music scene at the time, and the Hell Fighters band performed widely in France.) Africans and black Americans met in trenches, hospitals, railroads, shipyards and other places during the war, comparing notes and forging new alliances.

“The meeting of black Africans and Americans was explosive,” Mr. Caldwell said, noting the long history of black oppression in both countries and the brutal warfare among the white men claiming to have a civilizing mission. As a result, he said, black people returned to Africa wanting independence, and to America wanting civil rights.

After the war, the well-known Congolese scholar and former prisoner of war Paul Panda Farnana asked the Belgian government to put up a statue honoring the unknown Congolese soldiers. “That march for independence had started . . . with a simple request to erect a statue in honor of Congolese soldiers,” Mr. Caldwell said. “But I believe the nganga had already found an indigenous way to honor the Kongo dead, and also their meeting with their brethren from the other side of the world.”

Works by Ted Joans and Duncan Caldwell will be on display at the Oak Bluffs Public Library through August. For more information about the Oak Bluffs African-American Culture and Literature Festival, visit oakbluffslibrary.org.

Comments

Comment policy »