In letter written by 17th century French mathematician Blaise Pascal to a friend he is quoted as saying: “I would have written a shorter letter but I did not have the time.”

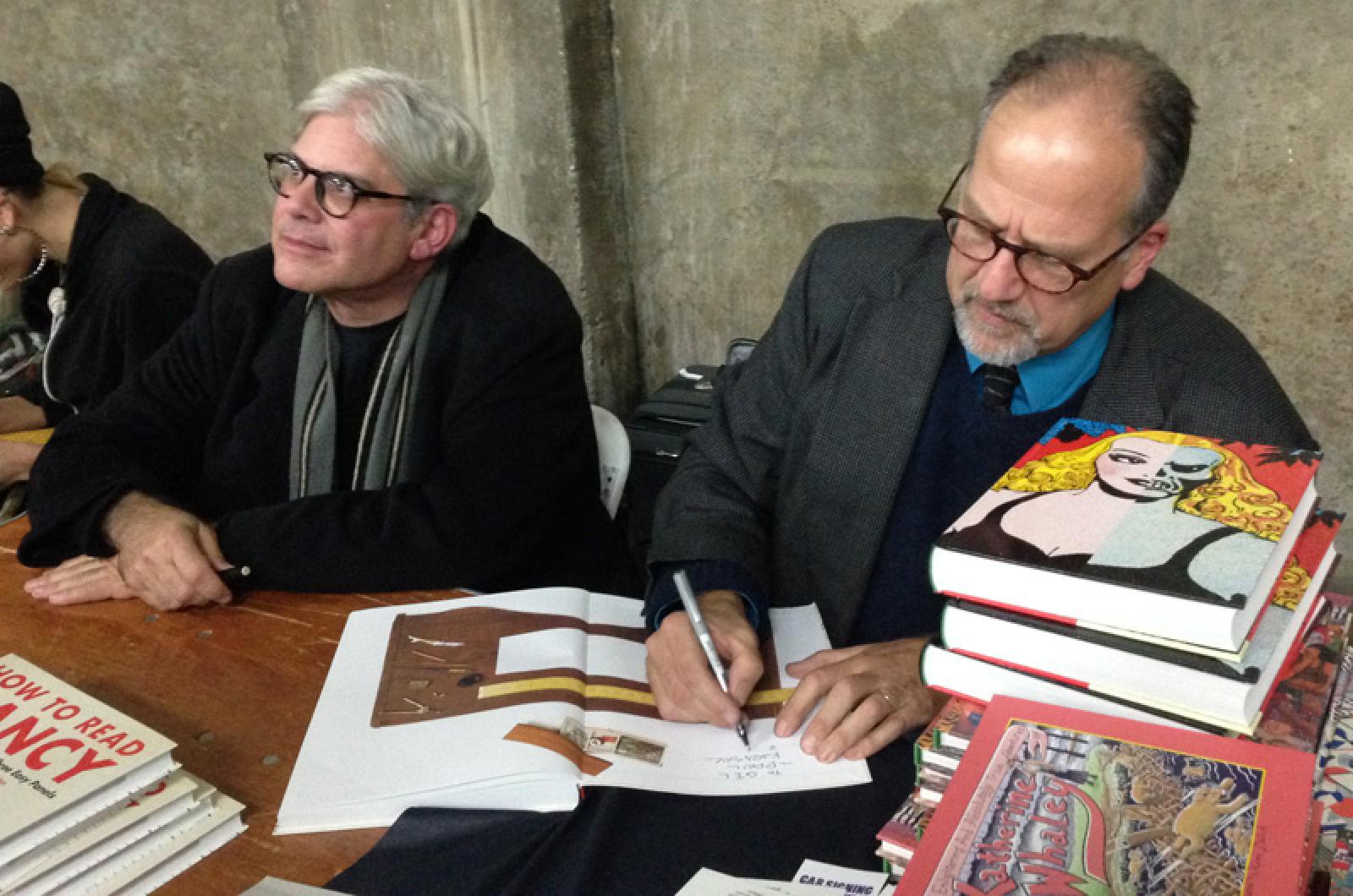

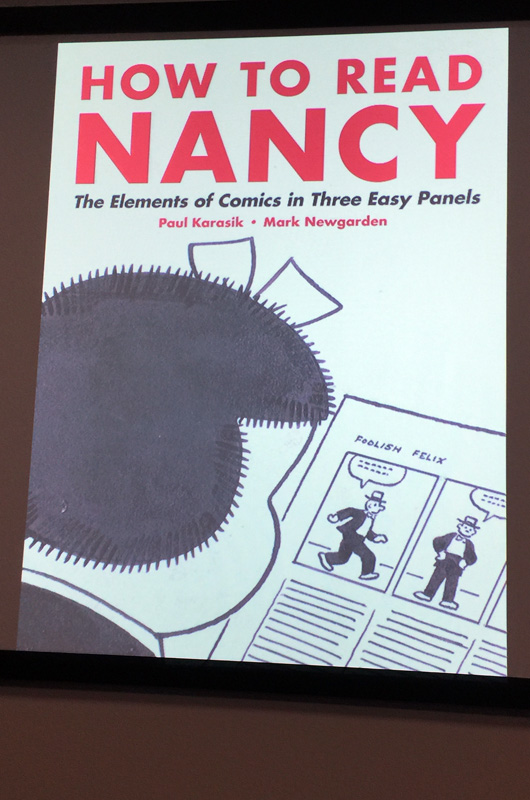

Pascal was referring to how easy it is to be verbose, and how hard it is to write something perfectly concise. The line serves as an epigraph in the new book, How to Read Nancy, by West Tisbury resident Paul Karasik and Brooklyn native Mark Newgarden.

In this case Nancy is the iconic comic strip that at its peak circulation in the 1970s ran in 880 newspapers. The comic strip began life under Larry Wittington in 1922 as Fritzi Ritz. In 1925 Wittington decamped to a rival publisher and Ernie Bushmiller took over the strip. Bushmiller debuted Fritzi’s niece Nancy in 1933 and the irrepressible little-girl-next-door proved so popular with her audience and her creator that in 1938 she became the title character. Bushmiller continued to author Nancy until his death in 1982. A succession of cartoonists has kept Nancy in publication through today.

It is on Bushmiller’s Nancy that Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden focus their attention. Mr. Karasik’s dual careers as a teacher, until recently the development director at the Charter School and currently a professor at the Rhode Island School of Design, and a cartoonist, most notably for The New Yorker, served him well in researching this book. Mr. Newgarden is also a cartoonist, creating the weekly feature Newgarden, working on the new editions of Wacky Packages and being part of the team that created the Garbage Pail Kids, among many other works.

The co-authors met in the 1980s at New York City’s School of Visual Arts in a class taught by Art Spiegelman (of Maus and Wacky Packs fame). In 1988 they wrote an essay about the comic strip Nancy but when they finished they realized there was much more to say about Bushmiller and Nancy, and decided to expand the essay into a book.

How to Read Nancy, published in November, is the culmination of this nearly 30-year journey.

In the authors’ defense, since those early days as students both have gone on to busy careers, and they have had to work under the confines of a long-distance relationship. Mr. Karasik moved to Martha’s Vineyard in 1989, while Mr. Newgarden, who resides in a repurposed funeral parlor in Brooklyn, has never been to the Island. But the authors will tell you that the distance is not why the collaboration took 27 years. Rather, perhaps that’s why it lasted 27 years.

The brevity the authors reference with Pascal’s line was Bushmiller’s calling card, and is in evidence in all of his work. The book, which includes a foreword by Jerry Lewis, chronicles the long career of Bushmiller, placing Nancy in a cultural context and juxtaposing it against other comic strips of the era. Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden pay particular attention to one prototypical Bushmiller three-panel strip from Aug. 8, 1959, breaking it down frame by frame, line by line, dot by dot.

In the preamble to the book, Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden write: “Just about everything that you really need to know about comics — reading comics, making comics, and understanding comics — can be found within the ruled borders of three panels published on August 8, 1959, and drawn by Ernie Bushmiller.”

In the first panel, Nancy spies her frenemy Sluggo, who, replete with toy cowboy gun holster, is saying ‘Draw, You Varmint’ to an unarmed neighborhood girl while squirting her in the face with a water pistol. In the second panel, Sluggo squirts another innocent victim. In the third and final panel Sluggo approaches Nancy from the front, uttering his signature line and about to unholster his water pistol. Nancy is also wearing a holster, but in hers is the business end of a garden hose (presumably equipped with a pistol-grip nozzle). Evidence of Nancy’s weaponry — the hose bursting with pent up water pressure, and its (implied) pistol-grip nozzle — are hidden from Sluggo by a backyard fence and the angle of Nancy’s pose. The bully, unbeknownst to him, is about to get his comeuppance.

Did you laugh at the retelling? Perhaps not. But a correspondent, who recently showed this strip to friends and family ranging from age 5 to 86, reports that most laughed. And two in the youngest demographic, who professed not to find it funny, absconded with the correspondent’s copy of How to Read Nancy to peruse the additional Nancy strips in the appendix.

In the book, the authors explain how Bushmiller’s rendering makes all the difference. The strip’s gag, that Nancy has a surprise for Sluggo, is reduced to its essence. Anything that is not needed to express the gag is discarded, including punctuation. Every detail, from location of word balloons to the size of and space between panels is considered. In the introduction, art historian James Elkins discusses Bushmiller’s skill in creating works of clutter-free detail in comparison to that of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian.

The result, as Mad magazine founding cartoonist Wally Wood noted, is that it’s easier to read Nancy than not read it. High praise for a cartoon on the crowded comics pages of the prior century.

“To dismiss Nancy as a simple strip about a simple-minded slot-nosed kid is to miss the gag completely,” the authors write. “Nancy appears to be simple only at a simple glance. Like the modernist architecture of Mies (“Less is more”) van der Rohe, Nancy’s deceptive simplicity is a deliberate function of a complex amalgam of formal rules laid out by a master of design.”

Bushmiller found many of his gag ideas in quotidian sources such as the Sear’s catalogue, but that does not preclude his work from being sophisticated. Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden remind readers that the New York World cartoon pages of Fritzi Ritz were targeting its adult readership. And the work of fellow New York World cartoonists at that time had a “modernist sophistication that would be at home on the early pages of The New Yorker.”

Bushmiller thinks enough of his audience and knows so well his subject that he is comfortable leaving much unsaid. Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden note that Hemingway’s line about well-written fiction from A Death in the Afternoon applies to good cartooning: “If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

The same can be said of nonfiction. Mr. Karasik and Mr. Newgarden took the time, 27 years, to explain as succinctly as possible the methods of a master of brevity.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »