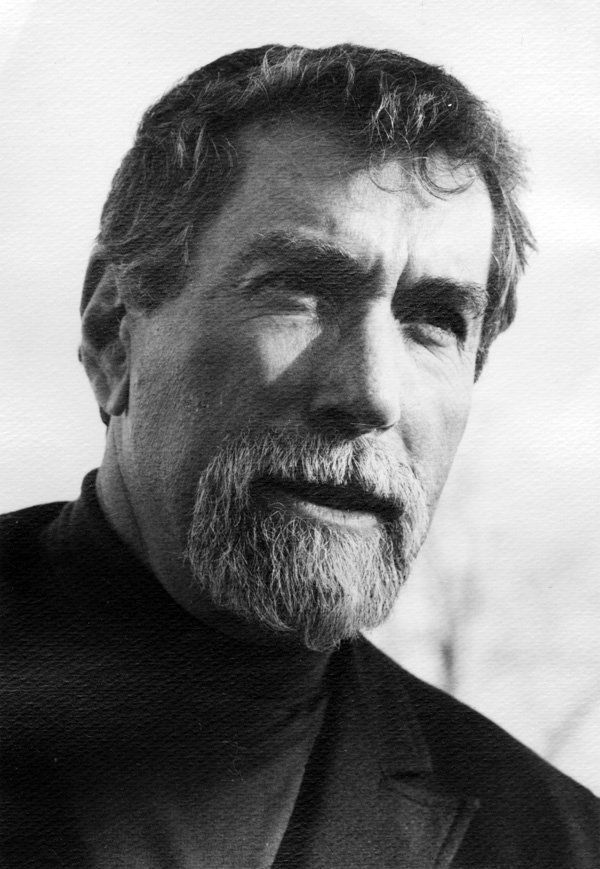

William Michael Goldsmith of Vineyard Haven, author, presidential scholar, political activist and retired professor, died Tuesday, March 23, of complications from a stroke at Long Hill in Edgartown. Goldsmith, 90, known as Bill, had a long and varied career that included work in the labor movement in the 1940s and 50s, civil rights activism in the 60s, and 24 years of teaching at Brandeis University. His life was marked throughout by a blend of scholarship and public service.

His three-volume documented study, The Growth of Presidential Power, was published in 1974 and is still considered by many to be the definitive work in its field. He also created the Brandeis Papers Commission at Brandeis University, a permanent repository for the papers of Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis.

Throughout his life, Bill maintained a penchant to connect with people from all walks of life and an ability to engage with a warm touch, a smile, or an insightful comment. He was the beloved husband of Dr. Marianne Goldsmith of Vineyard Haven, a psychoanalyst and pediatrician. They have three children and five grandchildren.

Goldsmith’s teaching career was remarkable for the inspiration and encouragement he gave to his students, especially the disadvantaged. He had a keen eye for the potential in each student he fostered and fought tirelessly to champion their cause. He was instrumental in bringing to Brandeis the groundbreaking Upward Bound program, a summer program for talented high school students from underserved neighborhoods such as Roxbury and South Boston.

Later, after grappling with the fact that many of these students’ educational backgrounds doomed them to failure at Brandeis, he helped found TYP, a transitional year program that continues to provide intensive academic remediation for entering students to ensure their success. One of Bill’s students, Gail F. Sullivan, a Boston lawyer who benefited from both the Upward Bound program and Bill’s personal mentorship, recently formed an endowed scholarship at Brandeis in Bill’s name, to which many of his former students have contributed generously.

Another of Bill’s achievements was his successful campaign to protect the area now known as Waskosim’s Rock Reservation from development. Bill fell in love with Martha’s Vineyard in the early sixties and, in 1976, Bill and Marianne bought a lot off Tea Lane, where they built a summer home. The beauty and serenity of the area was soon threatened by a plan to subdivide a nearby tract of land and build 32 luxury homes. Dismayed at the prospect, Bill initiated a lawsuit to enforce prior covenants specifying that the area would be kept “forever wild.” The litigation bought time, allowing Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation and the Vineyard Conservation Society to mobilize, engage neighbors and consolidate their resources. Ultimately, the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank purchased the tract, which has since been expanded to become one of the largest and most beautiful public areas of open space on the Vineyard.

Bill was born in 1919 in New York city to Margaret Theresa O’Rourke, an Irish Catholic manicurist from an impoverished background, and Otto “Mike” Goldsmith, a Harvard and Yale educated lawyer of German-Jewish descent. His father founded a law firm, Goldsmith, Cohen, Cole and Weiss (which later became Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison), but left the law to become a stock broker in the late twenties.

Bill’s early childhood in Forest Hills was idyllic. He spent his summer days working as a ball boy and watching the champions of the era play at Forest Hills. The family once took a luxury cruise along the newly-opened Panama Canal and traveled with 20 trunks and a governess by train to visit Mt. Hood. They spent leisurely weekends at Mike’s farm in Stamford, Conn. The stock market crash of 1929 decimated the family fortune. Bill attended Catholic University in Washington, D.C., but after completing his freshman year he left school to support the family. He worked a series of jobs — rug packer, longshoreman and Good Humor man — turning all his earnings over to his parents. During his spare time Bill began to read voraciously and to develop an interest in progressive political causes, activities that would form the core of his life and work.

In the summer of 1940, after reading How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler and Scott Buchanan, Bill — undeterred by the cast on his broken leg — hitchhiked the long road to Chicago. He was determined to meet with the president of the University of Chicago, Robert Maynard Hutchins, and to convince him to admit him to the university’s famed liberal arts program. Bill camped outside Hutchins’s office for several days before the president finally gave him a brief opportunity to state his case.

President Hutchins listened carefully, then told Bill that Chicago was not for him. Rather, he belonged at a revolutionary program at St. John’s College in Annapolis, the brainchild of a coterie of Chicago intellectuals, including Stringfellow “Winkie” Barr, Scott Buchanan and Mark Van Doren, and based on the 100 “Great Books” of Western thought. Hutchins made a few calls and Bill was in. The next few years were some of the best of his life, he recalled, reading and discussing ideas deep into the night, while waiting tables and working odd jobs, sending extra cash home throughout.

Bill’s college career was interrupted by the Second World War. He enlisted in the Air Force and shipped out to Guam with a Signal Corps outfit. While on active duty, Bill did not sit still. He developed educational seminars for Guam youth, supported integration of the mess facilities, and secured special orders to research and write histories of the other outfits in the Signal Corps.

Bill returned to St. John’s, graduated in 1948, and took a job with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, doing educational work throughout the South. He moved on to become the southern educational director for the Textile Workers Union. To Bill, the 1979 film Norma Rae accurately portrayed the desperate working conditions he witnessed during that time; he felt a kinship with the role of the union organizer, Reuben Warshowsky. After six years on the road, however, he grew weary of the field work and disillusioned with the union leadership.

In 1954, Bill returned to New York city, where he worked for the Ford Foundation and was admitted to the doctoral program at Columbia University, focusing on public law and government. He spent the fifties in New York studying, teaching and maintaining his involvement with politics and social issues. His studies culminated in a Senior Fulbright Fellowship to study at Oxford and to pursue his research on the origins of the Communist Front.

A chance meeting at a railway station in England changed his life. Marianne Lovink, a tall, beautiful Dutch student at St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, was from another background entirely: born in Indonesia and 19 years his junior, she was the daughter of a member of the Dutch diplomatic corps. He pursued her with the same dogged determination he pursued everything else he wanted in life: after six invitations, she finally relented. It was a perfect match. They were married in London at St. Margaret’s of Lothbury in June of 1959, and headed back to the states to plan a life.

The couple lived for a year in the New York area, where Bill continued his activism. He was participating in a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter when Marianne went into labor with their first child, Suzanne. In 1960, he landed a faculty position at Brandeis University and the growing family relocated to Waltham. They settled in Concord after the birth of Michael in 1962, followed two years later by Alexandra, or “Cricket.” The family committed themselves to the Concord community for the next 22 years.

At Brandeis, Bill taught in the politics department and became a founding member of a new, interdisciplinary department, American Studies. He taught primarily small seminars on the presidency and American political thought. In 1974, Chelsea House published The Growth of Presidential Power. Professor Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., in the introduction, praised the work as “indispensable” in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, noting that the academic community “will no doubt ... recognize [his] work as a remarkable tour-de-force of historical scholarship.”

Another scholarly project that Bill completed during his time at Brandeis was the creation and oversight of the Louis Brandeis Commission. Bill was deeply inspired by the public service work that Brandeis undertook when he was a lawyer in private practice. Under Bill’s direction, the Brandeis Commission collected, edited and created a permanent archive of Justice Brandeis’s pre-court papers.

Bill pushed his students hard, demanding they read widely and write prolifically. He eschewed final exams, but in many courses expected a paper a week. His office door was always open, and he did not only concern himself with their academic progress. He pressed them in every aspect of their lives, challenging many to use their skills to get involved and make a difference. He imbued his three children with the same values and ideals.

Bill retired in 1984. He and Marianne moved to White Plains, where Marianne completed a residency in psychiatry, and then to Providence, where Marianne practiced and Bill continued to write for 16 years. In 2002 the couple fulfilled Bill’s dream of settling on the Vineyard.

Bill is survived by his wife of 50 years, Dr. Marianne Goldsmith of Vineyard Haven; two daughters, Suzanne Goldsmith-Hirsch, of Bexley, Ohio and Alexandra Forbes, of Carmel, Calif.; a son, Michael, of Chilmark; five grandchildren; and a nephew, Mike Tenney, of Orlando, Fla. His older sister, Jane Tenney, predeceased him. The family plans a fall memorial. In lieu of flowers, donations in Bill’s memory may be made to the William Goldsmith Endowed Scholarship at Brandeis University or to the Vineyard Conservation Society.

Comments

Comment policy »