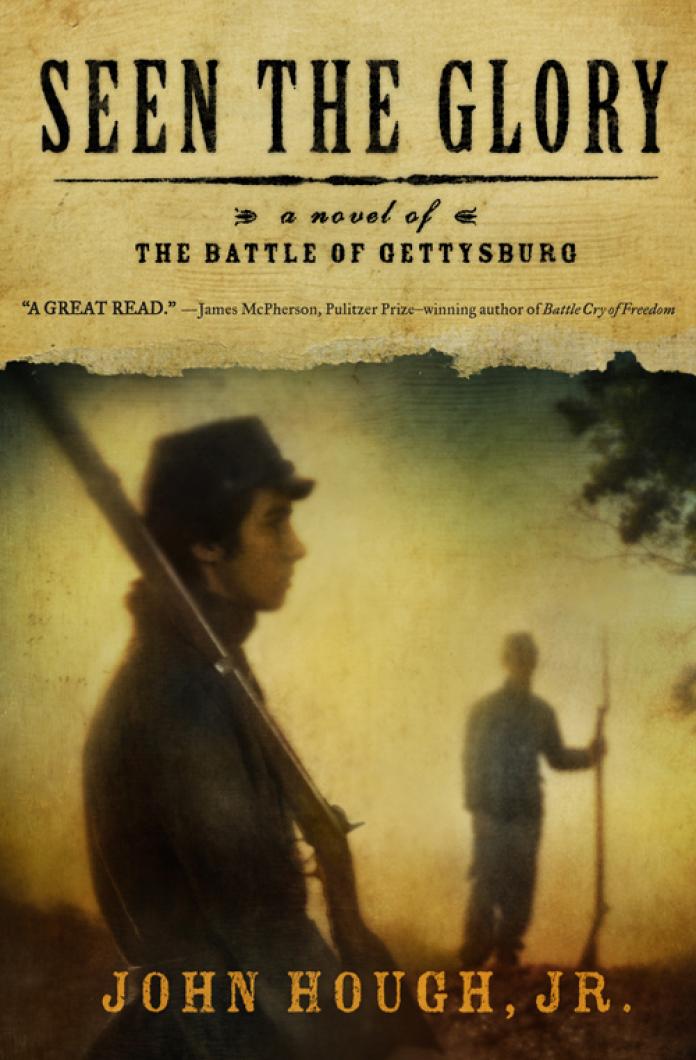

SEEN THE GLORY: A Novel of the Battle of Gettysburg. By John Hough, Jr. Simon & Schuster, June, 2009. 420 pages. $25.

The Vineyard comes off poorly in John Hough Jr.’s new novel about two Island teenagers who enlist in the Union Army a few weeks before the most consequential battle of the Civil War. No, worse than poorly: It’s an Island of bullies, bigots, shirkers, cowards and rapists. “The meanness would search you out,” a young Cape Verdean housekeeper realizes about halfway through the story, “even on Martha’s Vineyard, with its quiet ways and surface civility.”

Seen the Glory: A Novel of Gettysburg is a Simon & Schuster book, so it’s meant for a worldwide audience, and it’s fairly easy to imagine what sort of movie it might be turned into (expensive for one thing, with some young A-lister playing the lead role for another). But Islanders will likely wonder, at some point, why Mr. Hough goes out of his way to portray old Martha’s Vineyard as a place of physical beauty but such social darkness. Pretty quickly they may come to the conclusion that here, as in other fields of interest in this book, the author believes too little has changed over too much time.

For instance: When the story begins, the war itself is a badly bungled affair, dragging on far longer than it ever should have, the enemy depending in part on fanatics, insurgents and even terrorists to outwit, outmaneuver and outlast the liberators — whose leadership in Washington (by the way) looks incompetent, whose early generalship looks inept, and whose foot soldiers see through, and mostly scorn, the main cause for which the politicians have supposedly called them to fight (abolition).

Yet more: In the corralling of freedmen and native-born blacks in the streets of a Pennsylvania town by Southern invaders in the early summer of 1863, we’re meant to sense, I think, the first shadows of the Holocaust; in the beating and castration of a young African American who dares to defend himself from retreating Southern soldiers, the racial and tribal atrocities that carry on around the globe to this day. This is a book of terrible violence, naked racism and disturbing relevance to our own time.

And with one proviso, to be dealt with in a moment, Seen the Glory is also one of those books that can crowd itself into your life as you read it; you find yourself thinking about it during the day, wondering if, as evening comes, you’ll be ready to take in the percussive, searing ways Mr. Hough describes what happens on a battlefield — the forensically detailed fragmentations by which bodies are blown apart by an errant shell, the way a musket ball hisses past the ear, the way brigades are sent hopelessly up a hill and the way they get smeared away wholesale by the enfilades they charge into. There may be better descriptions of how Civil War infantrymen lived and fought and died. But I won’t be ready to read them for a while.

Mr. Hough weaves together four stories in Seen the Glory. As a whole, they show us how both a nation and two of its citizens collectively confront what will turn out to be the greatest crises of their young lives. For the United States, it’s whether the country can endure an improbably successful revolt by a zealous and canny foe. For the young Islanders, Luke and Thomas Chandler of Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven), it’s whether they can keep faith with their abolitionist ideals even as they risk their lives for them — not just in the face of hatreds that boil up everywhere they march and bivouac, picket and forage, but also in the face of a more personal hatred that suddenly threatens to cleave the brothers themselves right before the greatest battle of them all.

The Chandler boys — 18-year-old Luke and 16-year-old Thomas — are the sons of a quiet, widowed Island doctor, and living with them as cook and housekeeper is Rose Miranda, a young Cape Verdean, whose place and even safety in a suspicious and quietly hostile town is forever in question. All three Chandler men desire Rose, each in his own way. But it’s Luke whom Rose loves in return. This secret affair, and the risks it raises within the family and across the village, drives the main story. It’s largely because of his hope for a future with Rose that Luke enlists in the Union Army after the catastrophes of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Because Luke enlists, Thomas, lying about his age, does too.

As these two young men march together with the 20th Massachusetts regiment from northern Virginia toward the defense of Gettysburg, and then into the great three-day battle they fight there in the first three days of July 1863, the threat to this brotherhood of Luke’s so-far undisclosed relationship with Rose propels the second story. Spurring the third tale are the dangers Rose faces in predatory Holmes Hole after the two young men leave for war. Filling in the fourth are a series of events that show off the venomous race hatreds that prevailed everywhere — North and South — in those days and, insofar as this novel is concerned, shake to pieces the grandeur of the great cause for which the war is supposedly being fought.

The weakness here lies in the steadfast nobility of Luke’s and Thomas’s own abolitionist beliefs. It’s what animates their characters and sets them above most everyone they confront. But because Mr. Hough invests these lads with an unwavering certitude from the very first pages — at Holmes Hole, the Chandler family abets the freedom of a refugee former slave, at significant personal and legal risk to themselves — we know that nothing, neither the fearsome prospect of battle nor the searing revelation of the affair with Rose, will hazard those beliefs. They’re inviolate, and therefore less interesting than they might be if something or someone arose to threaten to pry them loose or knock them down. So we’re left to care about Luke and Thomas as two especially fine young Vineyarders who can’t possibly imagine what they’re in for at Gettysburg after just a few weeks of training.

So do we care? Yes, because of the world the author creates around them, the liveliness of the characters they encounter, the Armageddon they face on Cemetery Ridge just south of the town and the discomfortingly easy ways we may find parallels to our own time.

There’s one other thing, and it’s the salient selling point behind this book:

That’s the spare, urgent, enveloping quality of Mr. Hough’s prose. As a student of the Civil War, I’ve often yearned to feel what life was like during that time, and in Seen the Glory, he carried me back there as no writer has in years. Some of what he conveys may be too much for some readers to bear — the relentless ugliness of the racism, the descriptions of illnesses, the bloodiness of the fighting — but what edged into my own mind was how, each evening, I’d be called back to that time and place as almost never before:

“Thomas still held his gun uncertainly,” Mr. Hough writes of the hurried training the two boys get before being pressed into battle, “as if its purpose were a puzzle to him. He watched as Luke raised his, thumbing the hammer back through half cock to cock, two soft bright clicks, and sighted down the barrel at the far wall. ‘Get you a Reb,’ Elisha said, and Luke squeezed the trigger and the hammer fell, clack, and Luke knew he would, would shoot men dead before this was over, and without remorse.”

You like this language? You like where it’s taking you? You’ll like this book.

Tom Dunlop is the author of Morning Glory Farm and the Family that Feeds an Island, with photos by Alison Shaw (Vineyard Stories, 2009).

Comments

Comment policy »