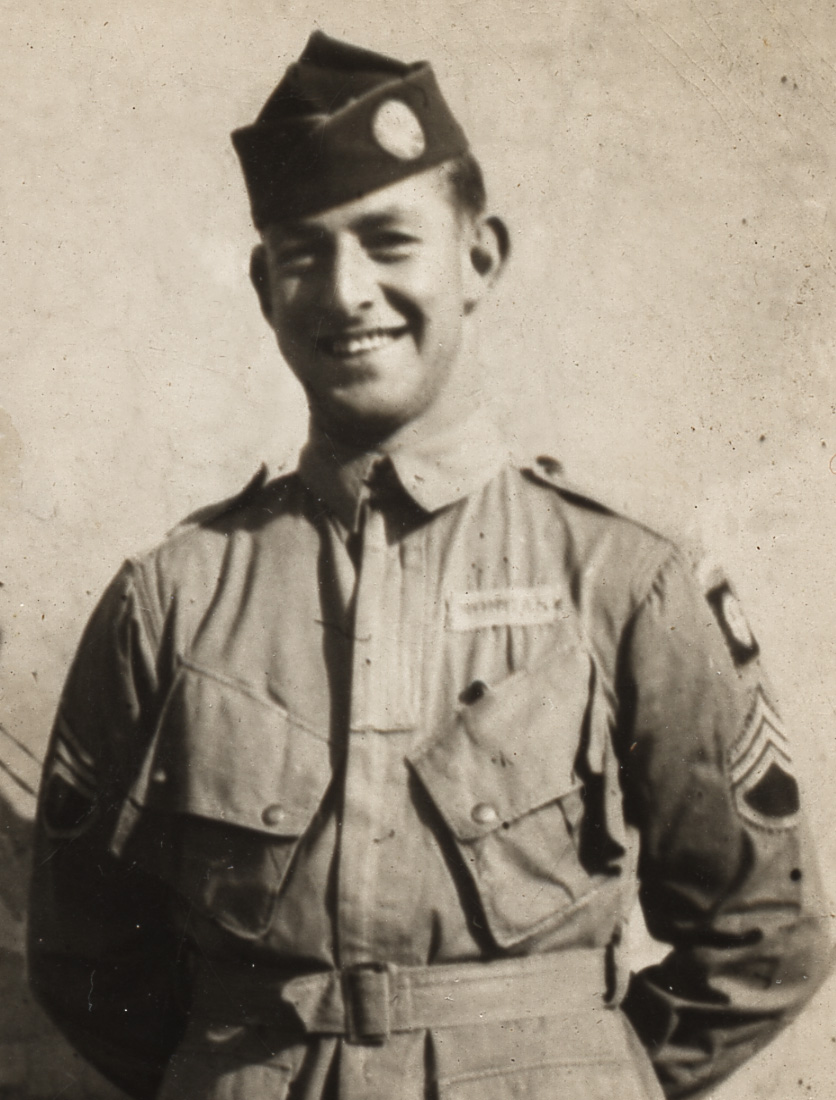

This is an edited excerpt from an interview done by Martha's Vineyard Museum oral history curator Linsey Lee with Fred B. (Ted) Morgan Jr. of Edgartown.

Mr. Morgan served as a medic with the U.S. Army's 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division. Ted fought in six battle campaigns that included combat and parachute jumps into Normandy as part of the D-Day operations; Italy, Sicily, Holland and the Battle of the Bulge. In 1949, Ted was called back into active duty with the U.S. Air Force and served in many capacities and in different locations until 1968. Retiring home to Martha's Vineyard, he became the administrator for the Martha's Vineyard Hospital. He was an Edgartown selectman for nearly 31 years and the longtime grand marshal for the Edgartown Fourth of July parade.

I had no plans for the future when I got out of high school. The idea of being a fisherman had no appeal for me. I left the Island to spend time with my uncle and aunt, who lived in Shrewsbury. That was where I met Floss, my wife. I knew her only briefly before I entered the army in January of 1942.

When I first enlisted in the Army, I wanted to go in the Army Air Corps. Unfortunately, they needed medical corpsmen in hospitals, so I went to Fort Devens and within a few days I was transferred to the hospital at Camp Edwards over in Falmouth. Then my duties consisted of working on a surgical ward from seven at night until seven in the morning, 12-hour shifts. I decided that I wasn’t going to spend the rest of the war doing that, so I thought about parachute school. They were advertising and also I was only making about $21 a month, and the extra $50 looked pretty good. But basically I just didn’t want to spend the war doing what I was doing so I thought, “Parachute duty? Sounds good to me,” never dreaming what it was all about and what eventually would happen.

Training at the U.S. Army Parachute School at Fort Benning, Ga., was unbelievable. None of us had experienced anything like it. We lost a lot of people just in the physical conditioning phase alone. The concept was to discourage one from completing the course. We started with a class of about 400, and 200 of us graduated. We trained in Georgia during the summer months — running, running, running all of the time — running with packs on our backs, with parachutes, a backpack and reserve chute in front. Running from place to place, calisthenics, rope climbing helped to harden us physically.

The third week consisted of mock-up jumps, which involved jumping out of an aircraft mock-up with a static line hooked to a cable, from a height of 30 or 40 feet. We would execute a parachute landing fall. As soon as our toes hit the ground, we would collapse and rotate in order to prevent the shock from affecting the extremities and allow the body to take the impact. We worked our way up to 250-foot towers that gave the sensation of the real thing. A parachute attached to a ring with a seat would go up and descend, bouncing on a spring at the bottom. It was scary. I was always afraid of heights when I was a kid. I wouldn’t dream of going into the steeple at the Methodist Church. Now all of a sudden, I’m faced with jumping from 250 feet.

I’ll always remember coming home on leave and seeing Pete Vincent at the Edgartown Drugstore. “Ted,” he said, “you’re not going to make it.” That stayed with me and I had to push myself. I couldn’t think of not doing it. I was absolutely determined that, if it killed me, I was going to prove Pete Vincent wrong.

After completing parachute school, I was assigned to the newly-formed 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, specifically to the medical detachment. I received surgical technician training and first aid training. As a medic, I wasn’t assigned a weapon and wore a Red Cross armband and that was it. When the troops were in combat, we were right along with them. I had enough to worry about without having to use a weapon anyway. When a trooper was wounded, a buddy would call “Medic!” The enemy fire would be coming in and we were right out there exposed to it. We always responded, regardless of the conditions.

Wounded paratroopers were transported back to the aid station, where they were stabilized. They would then be evacuated back through the medical and regimental chain, where, hopefully, they were transferred to a hospital in the area. There were times when we had numerous casualties and couldn’t evacuate them. There were no helicopters in those days, so we had to wait for the seaborne forces to come in and establish an evacuation chain. After their arrival on the beach, a hospital would soon be set up, in tents, of course. In Normandy, we had many casualties in different locations. We administered first aid the best we could, but, in many cases, we had to wait a day or two for the seaborne forces to come to our aid.

We jumped out of C47’s, the same aircraft that they used in combat situations. Our primary means of transportation all during World War II was a C47. My first combat jump was at night into enemy territory in Sicily. Our drop zone was close to a town called Gela. Col. James Gavin, our commander, landed a distance away from Gela in an area called Biazza Ridge. It was miles away from our original drop zone.

The password for that drop was George Washington. If you heard a rustling and you didn’t know who was there you would say “George,” and if you received the password “Washington,” then you knew it was your own troopers.

When you’re jumping at night into enemy territory it’s always terrifying and you just don’t know what to expect. Hopefully you’re going to land close to your own troops or they’re going to land close to you and you can assemble and go on to your objective.

When I first landed I was bewildered. I was all alone and all of a sudden it was quiet and I could hear dogs barking, and finally by wandering around a little bit I was able to contact some of the other men that had been in my aircraft. It was a very windy night and as a result we probably jumped from a higher altitude than we should have because the aircraft were not on target. The higher you bail out, the more chances of a wider separation. The idea is to drop low and as quickly as possible out of the aircraft so that the assembly on the ground would be much more effective. That night it didn’t happen.

Within 10 or 15 minutes, I was able to find a number of individuals who had bailed out of the aircraft. Also there were some supply bundles — para-packs — that were loaded on the bottom of the aircraft. They carried machine guns, mortars, extra ammunition, extra medical supplies and we did spot a couple of those that had landed close by. We were able to gather about 30, 35 men under the command of an A company commander, and then we started moving out. It really wasn’t until daylight that we started receiving enemy fire. Wherever we received fire from the enemy we would move in that direction. We had to move forward to capture our objective.

Because we had landed in so many different areas, every time the Germans turned around they were running into a band of paratroopers. So instead of reporting that only 3,000 had landed, they reported that 30,000 had landed. Fortunately, by the way we fought we were able to hold back the Germans so they couldn’t rush their tanks down to approach the seaborne forces coming in on the beach. And that was the plan, to hold back the armor and German forces so that the seaborne forces could land without opposition. And it worked.

Within a couple of weeks we took Trapani and by that time the major part of the war was over in Sicily. Gavin eventually became the 82nd Airborne Division commander, and he deserved every promotion he got. He demonstrated the epitome of leadership; he was always up at the front line; he was an amazing individual. I received a battlefield commission during World War II and he pinned my second lieutenant bars. I have that photograph in my den and I’ll treasure it forever.

Some of the Germans respected the Geneva Convention, and some didn’t. You never knew. You couldn’t rely on it. In Normandy we had medics killed taking care of the wounded and by the same token you’d run into a situation like I experienced where the Germans drove up in a tank and — it was amazing!

Charlie Lieberth, who was a headquarters company soldier in my unit, was very badly wounded in Normandy. He was probably struck by explosives fired by an 88-millimeter from a tank. He was bleeding and had fractures and shrapnel throughout. I rushed to his aid, and of course, the main thing is to stop the bleeding. In those days we used tourniquets and as I was working on him, administering first aid, a German tank started coming down the road and Charlie recognized this. All of a sudden he said, “Morgan, get the hell out of here! This tank’s coming along the road, there’s no point in both of us being killed!” I just kept concentrating on taking care of Charlie; there’s no way I was going to leave him, and he kept saying, “Get out of here! Get out of here.” I must have said, “Charlie, I’m not leaving.” And finally the tank — we were on the side of the road — the tank was even with us on the road, the cover of the turret opened, and a German sticks his head out of the tank and he looks down at us. Charlie says, “Oh, my God! They’re going to get us both! They’re going to kill us both!” All of a sudden the German pulled the cover shut, and the tank took off. And Charlie said, “Well, there is some honor on the battlefield after all.”

Of course, our casualties were extremely high in Normandy; the battalion that I served with went in with an average of roughly 140 men to a company, and 33 days later came out with an average of 21 men to a company. But that was the nature of the beast. You thought every minute the law of averages was going to catch up with you and that would be it.

I was wounded a couple of times, not seriously, though. I was hit with shrapnel in Normandy, basically twice. Once, another medic and I were moving up a hill to go after a casualty at the top of the hill. One of us had a litter and one had a Red Cross flag. The Germans spotted us and they were throwing mortars in at us, so we never did make it and I was hit in the hip with a piece of shrapnel and then we rushed back. We couldn’t continue on. Then another time in Normandy I was taking care of this mortar platoon sergeant, by the name of Fryar, about four or five days after the invasion. We were going through a town called Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte and we were digging in for the night on the outskirts and the Germans threw in everything they had in the way of artillery and mortars and this fellow, Fryar, was so badly wounded that he had a leg blown off and a large big piece of shrapnel in the chest. I couldn’t save him; there was no way; he was too far gone. And I still have a piece of shrapnel here in this finger. I had numerous small pieces of shrapnel throughout my back. They were superficial and I continued performing my duty as a medic.

After parachuting into Sicily, Italy, Normandy and Holland, and participating in six battle campaigns in the European Theatre of Operations, I returned home and was separated from the Army.

But I’ll always remember the people I served with, these troopers, who were just the most amazing people. Your friendships there, they’re of a different quality. You may not see an individual for years. You go to a reunion, he’s there. And it’s just as if it were yesterday. You start talking about the times when you were together and telling different stories.

It’s amazing, really, when I think about it. I’d never really been anywhere, traveled to any extent, and all of a sudden to get involved in something like that — to be able to do it! You know, I made up my mind, “My God, I’m going to do this!” and nothing was going to deter me. My pride alone. So I led a charmed life and was able to do this. I consider myself to be a lucky boy in every respect. Floss and I have had a great life and I couldn’t ask for more.

Comments

Comment policy »