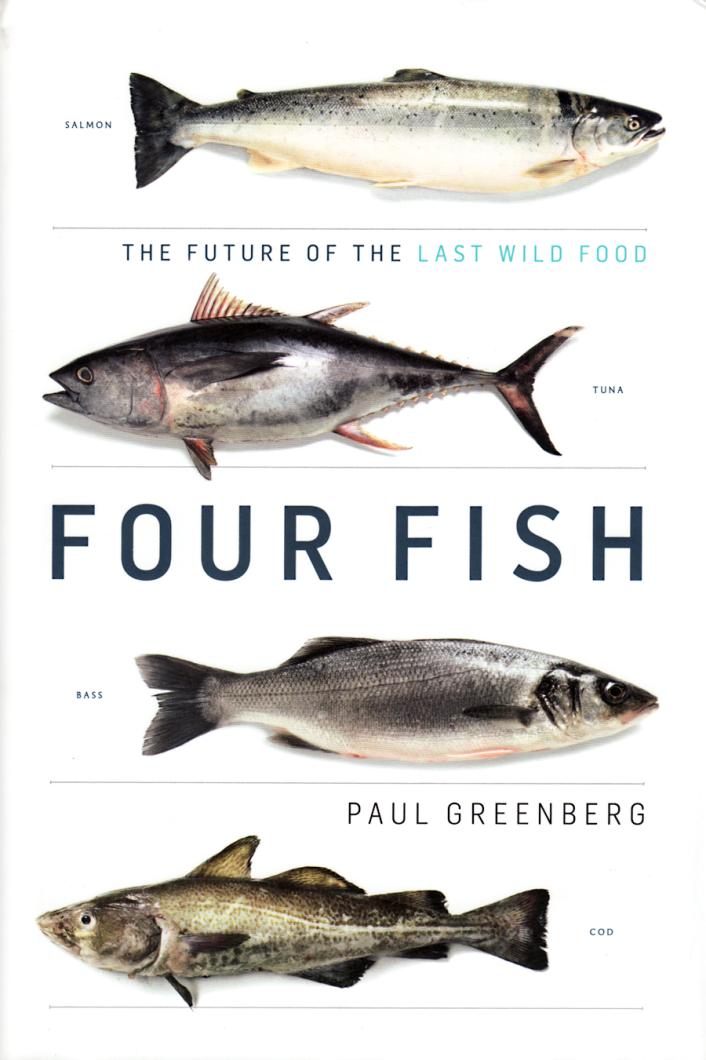

FOUR FISH: The Future of the Last Wild Food. By Paul Greenberg. Penguin Press, New York, N.Y. July 2010. 304 pages. $25.95, hardcover.

The title is too narrow. Don’t think for a moment this is a book only about salmon, cod, bass and tuna. The book goes beyond the history and plight of four fish, to our hunger for fresh fish of all kinds. For anyone who wonders where the swordfish went, how we emerged from the collapse of the whale fishery, or simply which fish is safe to order at the restaurant, Four Fish offers much.

Four Fish is an environmental story about our oceans and the outcome of centuries of harvesting. Mr. Greenberg’s superb narrative illuminates man’s domination of the oceans. He traveled to Alaska, to Norway and in between, putting together the stories that show how every step towards take and take and take has had a long-term impact on oceans — from the small skiff with an angler casting a line in the water, to international fishing fleets with football field-sized nets. Mr. Greenberg explains it so we all can understand.

A recreational fisherman, Mr. Greenberg is fuelled by his own history of pursuing the sea and hungering for connection to it. It is this sensibility that earns Four Fish the trust of those who come to the table seeking a deeper connection to the seafood they eat or catch.

Vineyarders well know that the ocean, our backyard, is nothing as it was a century ago. Codfish used to be as close to the Vineyard shore as the dingies that move about our harbors. Salmon used to swim up the rivers of New England. Bass, any kind of bass — there are so many varieties of bass — had far greater abundance than they have today.

As healthy meat, fish is now a resource under a lot of pressure. As the world’s population grows, there are not enough wild fish to go around. The resource isn’t sustainable even in the most idyllic vision of the future.

That means things have to change before some species drop below sustainable. But neither the consumer entering a fish market, nor the angler motoring out to the Middle Ground shoal, will likely do anything that will individually harm or save the fishes of the sea, Mr. Greenberg points out:

“It is not that we don’t have choices to make. But the choices ahead are large societal ones that require our careful attention and our active political engagement. After 40 years, beginning with the near global collapse of wild salmon, to the revival of the American striped bass, up through the closure of the cod fisheries on Georges Bank and Grand Banks, and on into the rise of more sustainable aquaculture alternatives like tilapia, we have seen numerous examples of oceanic disasters interspersed here and there with real improvements.”

This isn’t a book of advocacy. Mr. Greenberg neither tells the reader to stop eating fish nor to stop fishing. While engrossing and lucid, the author’s greatest achievement, perhaps, is sharing his understanding that the “man behind the curtain” in fisheries management is just another human. There may be boxes full of documents exposing that human’s foibles and significant errors in judgment, but the culture is changing for the better, if only slightly.

Mr. Greenberg draws attention to one issue that has deeply hurt the fish and fishing in the waters around Martha’s Vineyard: the shifting baseline.

In the past 40 years of managing the waters around this country, there has always been a dance between the fisheries managers and the scientists.

The scientists go out and analyze the catch reports of fishermen, they do their own sample fishing to establish the state of any species. It is a young science. Likewise, to monitor, manage and adjust the fishes of the sea makes for a young political force. And Mr. Greenberg’s overall view is that we as human stewards don’t do a very good job at it.

The “shifting baseline” is a term to describe scientists’ efforts to tweak the numbers. In Martha’s Vineyard waters, we’ve lost the cod, the pollock, the squeteague, the mackerel, the tautaug, the eel.

“Every generation has its own, specific expectation of what normal is for nature, a baseline. One generation has one baseline for abundance while the next has a reduced version and the next reduced even more, and so on and so on until expectations of abundance are pathetically low,” Mr. Greenberg writes.

Today’s fisheries biologists say the Atlantic mackerel is almost fully restored, though you can’t find a fisherman on the Vineyard who will agree to that. Mackerel could be landed by the barrel just 50 years ago. Today, mackerel swim past the Vineyard in a few short weeks and there are but a couple of fishermen who will try and make a day’s pay out of it.

For the rocking chair environmentalist who is trying to understand what beyond our shore we have so deftly destroyed, Four Fish is illuminating.

Mr. Greenberg’s book also gives any fisherman who seeks to understand the complexity of the problem a clearer picture, without eyes glazing over. It is Mr. Greenberg’s hope that future fishermen of our sea will have an education in fisheries that goes beyond the take mentality and involves the husbandry of the resource. So for every angler who goes to the sea and claims a right to fish, this book makes a perfect gift, as it is makes plain, through lively and persuasive storytelling, that with the right comes a responsibility.

Paul Greenberg will discus and sign copies of Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food on Monday, August 23, at 7:30 p.m. at the Bunch of Grapes Bookstore in Vineyard Haven.

Comments

Comment policy »