Martha’s Vineyard is growing rapidly more populous, older and more diverse according to the most recent figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

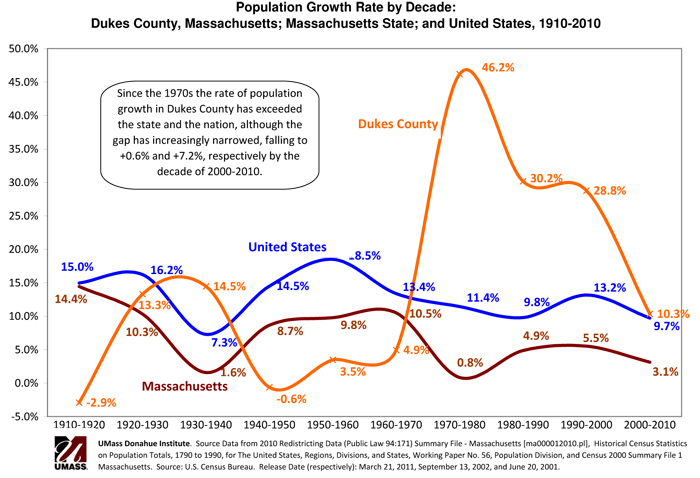

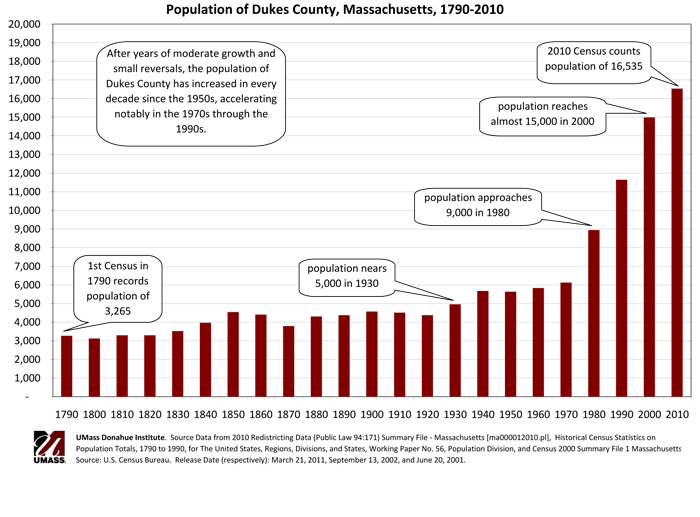

Overall, the population of Dukes County grew 10.3 per cent in the decade 2000-2010, well down on the 29 per cent growth of the previous decade, but still the highest by far of any county in Massachusetts.

There were wide variations in the growth rate among the six Island towns. The population of Oak Bluffs soared by a massive 22 per cent; at the other extreme was Aquinnah which shrank by almost 10 per cent. The other, tiny town in the county, Gosnold, declined in numbers even more steeply, by 12.8 per cent, to 75 individuals.

The population growth rates for the other four Island towns were: Chilmark, 2.7 per cent; Tisbury, 5.2 per cent; Edgartown, 7.6 per cent, and West Tisbury, 11.1 per cent.

The total population for the county was 16,535, according to the census bureau.

But there is reason to believe the census numbers represent a significant underestimate of the Island’s inhabitants. There are least 1,300 uncounted Islanders, and maybe several thousand, whose absence from the official statistics is costing the Vineyard millions each year in foregone federal and state funding.

Some of those people, sequestered in homes on the Island’s notoriously hard-to-navigate back roads, were simply inaccessible to census bureau counters. Others probably did not want to be found.

In the first category are 1,272 people who appear in the statistics kept by the town clerks of the six Island towns but who were not found by the census bureau.

“They should theoretically have a better count than I do, because they were going house to house,” said Tisbury town clerk Marion Mudge of the census effort. “But it’s very hard to find some of those houses down dirt roads.”

Maps used by the census bureau in the past have been woefully inaccurate. The various peculiar mailing arrangements Islanders have do not make matters any easier.

The towns have resorted to other means.

“We pick them up on birth certificates, dog licenses. We try to pick up everyone we can,” said Ms. Mudge.

Most cunningly, they pick them up via an arrangement with the Steamship Authority, whereby people not recorded on town street lists cannot get Islander preferred rates on the ferries.

In Ms. Mudge’s town, the result of that extra effort is that while the census recorded 3,949 people resident in Tisbury, the town’s own figure is 114 higher.

“So they’re not that far off, but each person is, I believe, worth between $1,000 and $1,400 in federal funds, not to mention representation for figuring congressional seats,” she said.

In Oak Bluffs the difference between the counts was 109, in Chilmark 264, in Edgartown 306 and in West Tisbury 339.

The apparent undercount is most glaring in Aquinnah. Town clerk Caroline Feltz said she had 451 listed town residents, including 398 registered voters. But the census only came up with 311 people, a disparity of close to 30 per cent. The fact that census workers apparently failed to find so many Aquinnah folk may help account for other anomalies in the data for that town in particular.

At least there are two firm figures to argue over in this category. There are no hard numbers, though, for the other hard-to-find group: immigrants, overwhelmingly from Brazil. Estimates of their number differ hugely.

Brazilians: Hardworking, Uncounted

The 2000 census identified just 213,000 Brazilians living in all of America. But a 1993 estimate by the Archdiocese of Boston figured there to be 150,000 in Greater Boston alone.

The Massachusetts Association of Portuguese Speakers estimates there are 800,000 to one million Portuguese speakers in the state; the largest component is Brazilian, and they believe Portuguese is the second biggest linguistic group in the state.

A 2007 analysis, Brazilians in the U.S. and Massachusetts: A Demographic and Economic Profile — by Alavaro Lima of the Boston Redevelopment Authority and Eduardo Siqueira of the Department of Community Health and Sustainability at the University of Massachusetts, reckoned there were 5,000.

Edivalda Santana of the Island’s recently formed Brazilian association claims there are 3,500 Brazilians on the Island, down significantly in recent years from as many as 5,000.

Yet the official figures put the total foreign-born population of the Island at just 1,748, or 11 per cent of the population. Philip Granberry, a research associate at the Mauricio Gaston Institute at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, said a breakdown of figures from the 2005 to 2009 community showed an estimated 752 Brazilians.

“And that number represented a growth rate of 101 per cent compared with the previous figures from 2000, when there were just an estimated 374 for Dukes County,” he said.

Of course that number cannot be cannot be right, as a quick look at the proliferation of Brazilian churches on the Island shows.

One reason many Brazilians don’t turn up in the census, said Mr. Granberry, is obvious: notwithstanding the census bureau’s assurances that its data is not shared with Immigration or other authorities perceived as threatening, “a large percentage are believed to be unauthorized [and] they don’t want to draw attention to themselves.”

The 2007 Lima and Siqueira analysis bolsters this theory, finding that only about one in five Brazilians was a U.S. citizen. Also about half of them spoke English “less than well.”

The Brazilian community, however, has some very attractive demographic characteristics. They work hard. More than 70 per cent of working-age Brazilians were recorded as being employed — the jobs are heavily concentrated in the services and construction sectors — and their unemployment rate was just four per cent. Most (58 per cent) were married, and of particular significance for an aging community like the Vineyard, they were young, with a median age of just 31.

There are other reasons too why Brazilians are not readily identified in the numbers.

For one, census authorities are not asking all the right questions. The data show that one in five Americans, and one in 10 Vineyarders speaks a language other than English at home. As to what that language is — Portuguese was not among the choices.

Nor do the broad census categorizations of race and ethnicity — including white, black and Latino or Hispanic — help identify Brazilians.

“Our analysis shows that for the state of Massachusetts in 2008, 70 per cent identified as white, and nearly 20 per cent identified as mixed or other race and only abut four per cent identified as Latino or Hispanic. That’s very, very low,” said Mr. Granberry.

And what is white anyway? As Henry Louis Gates Jr. noted in his recent PBS documentary, Black in Latin America, Brazil has a complicated racial history and 136 descriptors for the various skin tones.

Mr. Lima agreed. “There are many fine gradations in Brazil, and people can migrate from one to another,” he said.

Faced with a system of categorization far less nuanced than their own, it was likely “some people have been selective and they’ve seen . . . it as being to their advantage being white,” said Mr. Granberry.

Island Skin Color: Mostly White

Apart from the indeterminate numbers surrounding the race and ethnicity of Brazilians, the Vineyard remains a very white place.

Almost 88 per cent of residents classified themselves as white in the census, and 90.5 per cent are white or white mixed with something else.

A melting pot Dukes County is not. Overall, 96.6 per cent of people identified themselves as a member of one race category in 2010, and just 3.4 per cent identified as two or more races.

Given the Vineyard’s long, proud reputation as a racially-tolerant place, it has a remarkably small black component. Only 3.1 per cent identified as black or African American, rising to 4.8 per cent when mixed race was included. This of course does not include the large, seasonal influx of the black middle-class.

The category of American Indian or Alaska Native also was quite small — just 1.1 per cent, or 2.9 per cent among people of mixed races.

Less than one per cent of the Dukes County population was Asian, or 1.2 per cent if mixed race is included.

Hispanic or Latino described more than 16 per cent of the U.S. population; on the Vineyard it is 2.3 per cent.

Chilmark was the whitest town, at 96.4 per cent, followed by West Tisbury, 94.8 per cent; Edgartown, 88.3 per cent; Tisbury, 86.3 per cent; and Oak Bluffs, 84 per cent. Only in Aquinnah did the census numbers record a substantial non-white proportion: 42.4 per cent of the town’s residents. It was the Wampanoag tribe which made the difference — more than a quarter of the Aquinnah population identified as American Indian, and another 11.9 per cent as mixed race. In Oak Bluffs almost 4.9 per cent identified as black or as being of two or more races.

Small proportions, but they are growing — except for one historically important group. For the county as whole, the white population grew 6.6 per cent between 2000 and 2010. The black population grew more than 42 per cent, the Asian population more than 85 per cent, mixed races 19 per cent, and Hispanic or Latino almost 148 per cent.

The one group which declined was Native American, which fell by 28.5 per cent according to the census numbers. Here is where it is perhaps important to bear in mind the apparent 30 per cent undercounting of residents of Aquinnah, where the Wampanoags are concentrated.

Aging Fast

The Island also is an old community, demographically speaking, and one that is aging further and at a rapid rate.

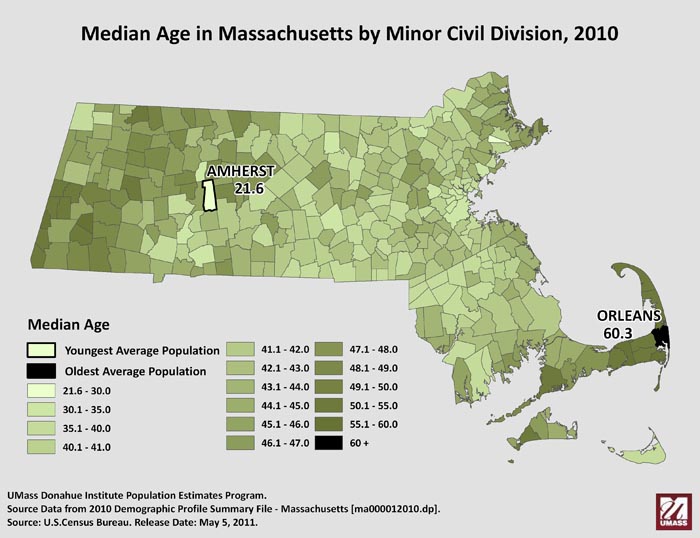

In fact, Dukes County comes in as the second-oldest in the state, with a median age of 45.6 years, somewhat more youthful than Barnstable’s 49.4, but way older than Nantucket’s 37.6, on 2009 figures. The median age for the state is 39.0, and for the nation is 36.8.

In 1990, the median age for Dukes County was 37; in 2000, it was 40.7. All of Massachusetts is getting older, but while the state median went up three years over the past decade, the Island’s went up 4.6 years.

Chilmark is particularly elderly, with a median age of 50.7, an increase of more than five years over what it was in the previous census. Almost 23 per cent of the town’s population is 65 or older. Of 351 communities in the state, ranked from youngest to oldest, it came in at number 332.

In descending order of elderliness, the figures for the other towns are: West Tisbury, 46.9, an increase of 4.9 years since the 2000 census; Edgartown, 44.8, an increase of 4.5; Tisbury, 44.3, an increase of 3.2; Oak Bluffs 44.4, an increase of 4.7 per cent.

Only Aquinnah has a relatively small population of people over 64, at 9.3 per cent, giving it a state ranking of 17. The town stands out, too, as the place where you are most likely to hear the laughter of children. Some 6.4 per cent of the population was under five at census time, a higher percentage than 90 per cent of towns in the commonwealth. Even so, Aquinnah’s median age was 45.5, compared with 37.1 a decade ago.

Housing: Abundant, Unavailable

The Vineyard is distinguished too from the great majority of communities in that it has almost as many houses as it does residents. The census records a total population for Dukes County at county of 16,535, and 14,836 housing units.

In three towns, houses outnumber year-round residents. In Chilmark there are 1.6 houses per permanent resident; in Aquinnah, 1.5; in Edgartown 1.05. In Oak Bluffs the ratio of houses to residents is 0.84; in Tisbury 0.68; in West Tisbury 0.67.

Yet despite this superabundance of housing, vacancy rates, as most people think of them — homes available for rent, but not occupied — are extraordinarily low. In Chilmark at census time the percentage of vacant houses for rent was 0.5 per cent. Comparable rates in the other towns ranged from 1.7 to 2.5 per cent, except for Tisbury, where it was 5.1 per cent.

The reason is obvious — seasonal residents — but that is no comfort to year-rounders trying to find a place to rent. Nor does it make the statistics any less startling.

In Chilmark, fully 75 per cent of all homes are used for recreational purposes and vacant most of the time. In Aquinnah the number is 70 per cent; in Edgartown 66 per cent; in Oak Bluffs, 54 per cent. Only West Tisbury (45 per cent) and Tisbury (42 per cent) have a majority of year-round residents..

Among occupied houses, two-thirds are owned and one third are rented.

The percentage of family households stood at 57.3 in 2010, down from 64 per cent in 2005-2009. Non-family households, conversely, went up from 36 to 42 per cent. More people also lived alone.

Many of them have a tough time financially, a fact apparent in the data, belying the reputation of the Vineyard has in much of the outside world.

The 2005-2009 American Community Survey, a more detailed accounting than the census itself, released last December showed home values in some Island towns ranked with the highest in the nation.

The median home value in both Chilmark and Aquinnah was over $1 million (the survey did not distinguish prices above a million). The lowest median home value of the six Island towns was in Tisbury, where it was just under $600,000.

Yet per capita income in Dukes County is pretty much the same as that across Massachusetts, around $33,500.

Not surprisingly, Island renters and mortgage-holders are under great financial pressure, with a majority shelling out more than 30 per cent of their household income on housing and even among those who own their homes outright, one in three find that housing costs eat up a third of their incomes .

No wonder Island families increasingly need two incomes to make ends meet. In 2000, about 57 per cent of Island children under six had both parents in the labor force; now the figure is 87 per cent.

On the on the hand, Islanders are educationally well-equipped for the struggle. Overall, 40 per cent of adults in Dukes County had college degrees, compared to 27.5 per cent of Americans. Chilmark, where 69 per cent of the population age 25 and older has a bachelor’s degree or higher, only narrowly loses to Falls Church, Va., as the country’s best-educated place.

The community survey found a poverty rate of about eight per cent, compared with the national rate of 14.

So if you had to sum up the salient demographic features of the Vineyard at the start of the second decade of the 21st century, it would be something like this: old and getting older, very white but getting less so, expensive but not affluent, playground of the rich but home to the educated battler, and dependent for much of its labor and remnant youthful vigor on a group of people who we can’t even count.

Comments (4)

Comments

Comment policy »