Southern New England is overdue for a major hurricane. The last big one, in terms of lives lost, damage and cost, was the Great Hurricane of 1938. A lot has changed since then that will make the next one even more severe.

The hurricane of 1938 was fast-moving, there was little advance notice and the destruction was immense. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that pressure systems similar to one that caused it to move so quickly still exist today. Advance storm notice has improved but the coast is far more populated and developed and the sea around us is rising, which will create bigger storm surges and more coastal flooding — more water, more people, more property, more damage. The scientific consensus is that warmer oceans, due to human-induced global warming, will cause fewer but more intense hurricanes.

“A major hurricane will strike New England again; only uncertainty in the size and timing of the event remains.” This is the conclusion of a study done by Risk Management Solutions, Inc., in a report entitled, The 1938 Great New England Hurricane; Looking at the Past to Understand the Future.”

Last year Hurricane Earl threatened the Island but swept out to sea at the last minute. People groaned about business and road closures, about preparedness overkill. This is a short-sighted attitude because hurricanes are deadly — to humans, property, the environment and the Island economy.

NOAA cites a report that puts the price tag for a category three New England hurricane today at up to $70 billion. The highest category is five (the 1938 hurricane was a three when it hit land).

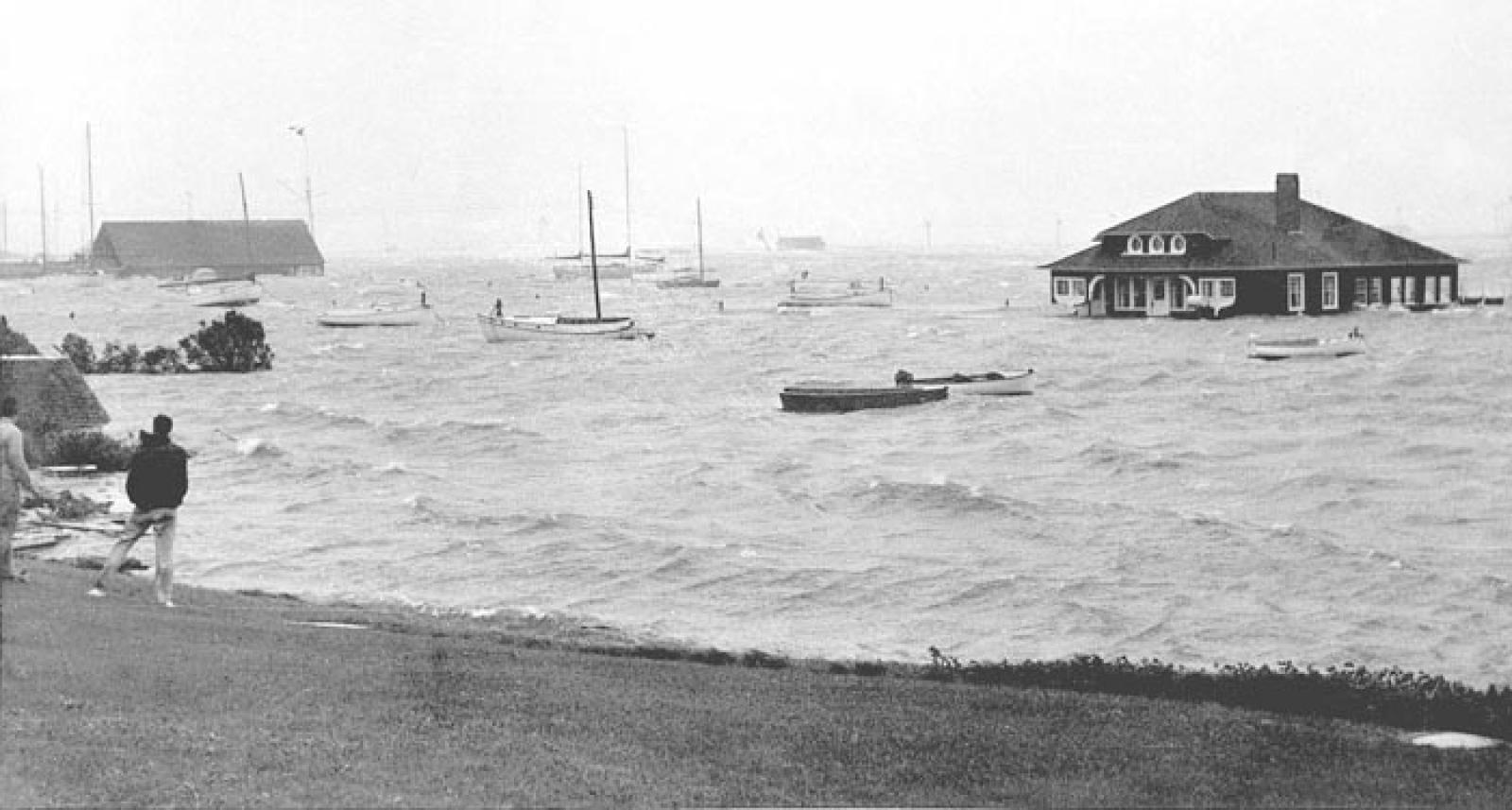

County manager Russell Smith learned from his grandfather that on the day of the 1938 hurricane many people were birding on the south shore; for many years after the storm his grandfather, a surveyor, came across decaying decoys and other storm debris far in the woods across the south side of the Island. Buildings were lifted off their feet; one Mr. Smith is aware of was carried half a mile or more inland. Some reports said 50 feet of the south shore washed away that day. Across the region over 600 people died, over 1,500 were injured, and up to 275 million trees were felled. Hurricanes deserve our respect; they are far more powerful than we are.

Northeasters, our more common local storms, are also at the whim of global warming-induced climate change. According to the New England Aquarium, northeasters are “lower-energy storms that occur more frequently, last longer and cover more area, causing significant damage . . . named for the strong winds that generally hit the coast from the northeast between April and October.” Since the 1970s, northeasters have struck New England more frequently and with greater intensity, the Aquarium reports.

Sea level rise will increase the severity of hurricanes and northeasters. The U.S. Global Research Program reports that in the Northeast, sea level rise “is projected to rise more than the global average . . . the densely populated coasts of the Northeast face substantial increases in the extent and frequency of storm surge, coastal flooding, erosion, property damage, and loss of wetlands.”

Storm surge is water, in great volumes, that is pushed toward shore by wind force during storms. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), “The greatest potential loss of life related to a hurricane is from the storm surge.” The surging water can cause flooding and damage far inland, especially when storms hit at high tide.

The surge at high tide in the 1938 hurricane “sent 13-foot storm surges into parts of Narragansett Bay and Buzzards Bay. Storm surges washed over nearly every barrier beach in the region and cut many inlets through them,” declared a 2007 report titled, Confronting Climate Change in the U.S. Northeast. On the Island, water surged across the south shore and the ponds and slammed into the village of Menemsha.

FEMA reports: “With major storms like Katrina, Camille, and Hugo, complete devastation of coastal communities occurred. Many buildings withstand hurricane force winds until their foundations, undermined by erosion, are weakened and fail.”

Waves are also growing restless. In her book The Wave: In Pursuit of the Rogues, Freaks, and Giants of the Ocean, author Susan Casey writes that “average wave heights have also been rising steadily, by more than 25 per cent between the 1960s and the 1990s.”

Wind, water and waves trump humans at every turn. More severe storms on the Vineyard will put at greater risk coastal homes, roads, seawalls, bridges, utilities, beaches and salt marshes, boats and marinas, fisheries and aquaculture. A major hurricane will cripple the local economy.

More importantly, severe storms injure and kill people: family, neighbors, friends. As buildings break apart, their pieces become flying torpedoes of destruction. Washed-out roads inhibit rescues and evacuations.

In their book, Changing Planet, Changing Health, Dr. Paul Epstein and Dan Ferber discuss the health risks that follow major storms. “No nation is immune from such disasters,” the authors write. Especially as the climate warms. Health risks include the loss of water supply and sanitation services, diarrhea, respiratory infections, rodent and water-borne diseases, bacterial and viral disease and vector-borne infectious disease “that enable vector species like mosquitoes to breed.”

Authors Epstein and Farber cite examples from Hurricane Katrina: “Physical injury, homelessness, heatstroke, severe hydration and stress, which brought on heart attacks and strokes.” There is also the “Katrina cough . . . a persistent cough, inflamed nasal passages, infected eyes, and the like, which many blamed on rampant mold left behind by receding floodwaters.”

Loss of homes and jobs, they write, can bring on mental stress, including depression and “in the two years that followed (Katrina) suicidal thoughts and plans more than doubled.”

This is a piece of our future on bright, sunny Martha’s Vineyard. A hurricane will come our way, sooner or later, while increasingly angry northeasters whittle away at our shoreline.

What can we do? The big picture is this: Humans must move quickly away from the use of greenhouse gas-inducing fossil fuels to cleaner energy. On a local level we can help make this happen. One way is to write to your local, state and federal representatives and demand action on clean energy. Clean energy will create jobs. Investing in clean energy projects, if you can afford to do so, will help stimulate their growth. And think of what you can do in your home — get an energy audit, for starters — and volunteer in the local clean energy community.

When a hurricane is headed our way take it seriously. The threat is real. Pay attention to the weather, remove potentially wind-borne debris from your yard, take the Island’s reverse 911 messages to heart, get bottled water, nonperishable food and a manual can opener, a first aid kit, prescriptions, flashlights and batteries. Charge your cell phone. Log onto the National Hurricane Center Web site for more information on how best to prepare. If you live near the water, move to higher ground.

Tornados, massive floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, hurricanes — they never used to be in the news every day. Now they are and the Island is not immune.

The sea is rising, churning, and gaining power that humans are ill-equipped to handle. We need to understand the threat and act accordingly — be prepared and get involved. Be a squeaky wheel, make a difference.

Liz Durkee is the conservation agent for the town of Oak Bluffs. This is the seventh part in an occasional series she is writing for the Gazette Commentary Page about climate change and what it means for the Vineyard.

Comments

Comment policy »