David McCullough laughingly calls the pretty little eight-by-10-foot structure in his back yard his “world headquarters.” Naturally, he was keen to pass on the details of its architecture and history.

“This is where I’ve worked since 1972,” he said. “It was built by Alan Miller, an artist with carpentry. He built the Black Dog in Vineyard Haven. He built numerous buildings around the Island, all distinctive.”

Mr. McCullough pointed out his HQ’s salient features — the high ceiling and windows in all four walls, which catch the breezes and ensure it never feels claustrophobic. And the most important thing of all: on the small desk an elderly Royal typewriter. He caressed the dished, glass-topped keys.

“It was made in 1940. I bought it secondhand in 1965 when I started my first book; I think I paid about $25. Everything I have written, I have written on this typewriter. And nothing has ever gone wrong with it. It’s looked after by Denny da Rosa in Oak Bluffs. He gets me the ribbons and every once in awhile we have to have the roller replaced.”

“Sometimes I think it’s writing the books,” he said.

It seems apt that a man who has made his life digging up the gems of the past should record his finds on such an artifact. And while he does have another office at his West Tisbury house with all the conveniences of modern communication, he would never write on anything else, for a couple of reasons.

First, it never breaks down. Second, he credits it with having protected him from repetitive strain injury. Third, he does not put much stock in speed.

“If anything I would rather go slower,” he said. The part of writing that takes the most time is not typing, but thinking.

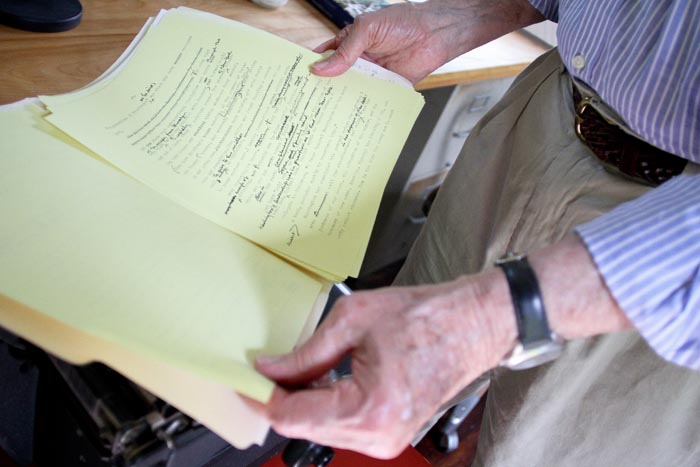

So he hunts and pecks at the keys — “I’ve never really learned how to type” — then scribbles corrections all over the work. He pulled out a couple of pages of drafts as an example. “It looks like the work of a madman, doesn’t it?” he said.

Then he and his wife, Rosalee, read it aloud to each other, “because you hear things you don’t see, [like] the repetition of a word or sentence structure.

“I’m not a writer,” he said. “I’m a rewriter.”

The formula obviously works; two Pulitzer prizes, National Book Award, Presidential Medal of Freedom and Mr. McCullough’s status as the go-to guy to narrate historical documentaries attest to his status as the country’s pre-eminent popularizer of history.

So does the level of interest in his latest and, he says, most personally satisfying work, The Greater Journey, a history of Americans in Paris between 1830 and 1900. It was widely reviewed and Mr. McCullough was all over the nation’s media like a rash.

Some idea of the level of interest and the breadth of his appeal may be gleaned from the fact that on the same day last week, July 13, he had a piece on the New York Times op-ed page about America’s relationship to France, and also appeared on Comedy Central’s Colbert Report — during which he was called upon to lend his mellifluous tones to a reading of some racy rap-song lyrics.

He enjoyed it all; he loves talking about his subject and meeting his readers.

“But it was exhausting, and I’m not 72 any more,” he said.

Now though, the tour, the most arduous part of the process of putting a new work out there, was behind him. And seated in the shade of his backyard on Music street, he was relaxing into “a summer of putting my feet up,” and happy to talk at length about a whole range of things besides his book.

In conversation, as in print, Mr. McCullough segues easily from one thing to another, supplying facts and dates as he goes, and in the rare instances where he is not quite sure, asking to be fact-checked.

First up, the West Tisbury library. Mr. McCullough will speak at a benefit for the library at the Agricultural hall on Wednesday night. Tickets are $35 each, and it is already sold out.

He said he is doing it for the love of his town, and the love of books.

As might be expected, he is well-researched on the subject of the town library.

“West Tisbury has an extraordinary characteristic, that I don’t believe could be claimed for any other town, that I know of anyway,” he said. “Eighty-nine per cent of the population of West Tisbury has a library card. You can double check that with the librarian.”

He was right.

From the history and architecture of the library, he moved on to that of West Tisbury and the whole Vineyard, via music.

“The more I think about it, music and architecture seem the two most important forms of art in that they . . . surround us,” he mused.

“And they can transform the feelings of the moment. You can be stuck in a traffic jam, and some magnificent piece of Gershwin comes on the radio and it just eliminates the frustration, the anger, the aggravations.

“You know why this is called Music street?

“When sea captains retired from whaling, most of them wanted to be as far from the ocean as they could get on Martha’s Vineyard. They’d seen enough water. So they settled here.

“And one of the status symbols, if you will, was to have a piano in your house and a daughter taking piano lessons. And supposedly there were pianos up and down this street. And that’s why it became known as Music street.”

Mr. McCullough loves that history, loves the knowledge that the home of Joshua Slocum, the first person ever to have sailed alone around the world, still stands near his, loves the way history is apparent in the architecture of the place.

“[It] is to a large extent what gives this place its appeal. You can’t ever take that for granted. You have to appreciate it,” he said. “It is architecture designed by people who weren’t architects, but somehow they had a sense of proportion and of what to do.”

From the history of the Vineyard, it was but a short step to his own history on the Vineyard, which began in 1951, when he met Rosalee Barnes, the woman from an old Island family who would become his wife. They met in Pittsburgh.

“And she said, ‘You might like to come and visit Martha’s Vineyard sometime.’

“Of course at 18, the most important thing in life is to be cool, so I said I would like to do that very much. Then I went home that night and . . . got an atlas down off the shelf and looked and went, my God, it’s an Island!

“So I came chasing a girl. I arrived here the first time 60 years ago this summer.”

He loved the place, and happily boasts that their grandchildren are sixth-generation Vineyarders.

Mr. McCullough has not been a year-round resident for a couple of years now, something he ascribes to the fact that his children and grandchildren make their homes elsewhere.

“But we all come swarming back at the first chance. This is home. If you want to see your grandchildren, have a home on Martha’s Vineyard.

“The pull of grandchildren is very, very powerful. It’s one of the most pleasurable surprises in life. It’s like tasting some food or drink you’ve never had. It’s wonderful,” he said.

And so by this circuitous route, we finally arrive at the book. For it turns out there is a place that fired his imagination before the Vineyard and it was Paris.

Images which grace the inside front and back pages of the work are taken from postcards his mother collected there on a trip she made to Paris in 1907.

“I grew up hearing about her childhood trip,” said Mr. McCullough. “And then my oldest brother went and he came back with all kinds of stories. I grew up in Pittsburgh, and one of our local heroes, same neighborhood, was Gene Kelly. Of course he starred in An American in Paris. So as a kid I was impregnated with Paris.”

The first time he and his wife went there, he was working with the U.S. information service, during the Kennedy administration. “We were flying to Morocco . . . and we landed in Paris, and it was after dark after a long flight, February, raining, cold as hell and we put our bags down in a little hotel on the Left Bank and went out walking for about two hours, utterly thrilled to be there.”

He has returned innumerable times, for research on several previous books, and for pleasure.

When he decided to write about it, he realized there was a hole in history.

“The Jefferson/Franklin/John Adams period of the 18th century had been written about. So had the so-called lost generation of the 1920s and 1930s. But there was a big chunk of time — 70 years — at which nobody had taken a close look.”

So he did.

The Greater Journey is a significant departure from his other work. It is not about a single central character, like his President books. Nor is it about a single event, like the Johnstown flood, or the building of the Panama Canal, or the Brooklyn Bridge.

“With this book . . . I could cast it as I wished,” he said.

But if the book was to be more than a simple catalogue of names, he had to set criteria. Subjects had to be people of particular talent, ambitious to excel in their fields, changed by experience, either in work or personally.

“And they had to have written about it in letters, diaries, or memoirs that were done close enough to the experience that they weren’t subjecting us to mistaken memory,” he said. And so, as he puts it, he invited characters in to audition for him. Many did not make the cut.

“I was interested in what they brought home and how it shaped us. They can bring home something, literally, like a great work of sculpture, like [Augustus] Saint-Gaudens, or they can bring home a revelation such as [Charles] Sumner had about how we treat black people in this country. He happened to think about how black students were treated at the Sorbonne, where he was studying. And it transformed him into an ardent abolitionist. So he gets into politics and becomes the most powerful voice for abolition in the Congress, and changes history, almost at the cost of his life.”

He cited examples of what people brought back too numerous to mention. For those, you must read the book, but one in particular surprised him: a formerly little-remembered American political figure, Elihu Washburne, who became ambassador to France at the time of the Franco-Prussian war.

“He was for me one of those surprises that make life so wonderful for a writer. I had no notion of Elihu Washburne when I commenced work on this book, nor any premonition that we were going to discover a diary that’s like nothing I have ever had happen to me in my working life. It was the most exciting discovery of my writing life, that diary.”

David McCullough has never begun a book because he was an expert in the topic. Quite the reverse. He writes, he said, because he wants to learn about a subject which has caught his interest.

Mr. McCullough’s work requires a great many things: painstaking research, tenacity, endless rewrites. But in essence, it comes down to two things.

Find something that interests you, and make it interesting for others.

Comments (2)

Comments

Comment policy »