Editor’s Note: The following story was published in the Gazette in August 1961 on the occasion of the fair centennial.

BY JOSEPH CHASE ALLEN

There is no one, of course, who can remember the Island fair as it began, or for that matter, for many years after it had become a recognized institution. Yet there are old, musty records to be unearthed, items in old copies of the Vineyard Gazette, and folk-tales, still remembered, all of which add up to something approaching a picture of that day and year when the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Society Fair was new.

Names of men long forgotten are to be found in these old records — Hebron Vincent, Capt. Francis Rotch, a whaleman of distinction, John Davis, “for whom the Lord made water run up-hill,” according to popular comment, Charles B. Allen, the judge of the home-made wine, David Look, one of the Island millers, and — Ewing, first name forgotten, the most famed of all Island hewers of timber at that time; together with many others.

It may be assumed that the appearance of the hall and grounds was much the same as of today, insofar as the outward view of the building is concerned. The assembly hall on the second floor was a drill hall, with a flooring of pine planks inches in thickness. There was a tiny armory in one corner room, where the muskets were racked, and the students of the Academy got their military training there, under the instructions of one ex-Corporal Norton from Davistown, who had served in the Regular Army.

On Long Wooden Benches

In that early day of the fair, the upper floor was not used for the display of exhibits. Instead it was furnished with long wooden benches, built in the furniture factory of Mayhew and Adams in Oak Bluffs, and here, in the long afternoons, the patrons of the fair assembled to listen to selected speakers, quite frequently from some state department or even federal, who talked of crops and livestock and offered sage advice on planting, fertilizing and breeding.

It may be thought that the introduction of pure-bred stock on the Island is something that belongs to the recent years. This is far from the truth. As a matter of fact, pure-bred animals had been imported to the Island before the fair was established. The pure-bred Devon bull of Joseph C. Allen had arrived long before, and Prof. Henry L. Whiting, the principal founder of the society, had purchased and shipped to the Island a herd of pure-bred milch cows as well.

These had been auctioned on the fair-grounds, at one of the early fairs, bringing an average price of $250, which was remarkable in that time. Yet the purchasers, recorded, list Capt. Rotch, John Davis, Hebron Vincent and two or three others, and it was not apparent that any difficulty attended this sale.

There Were the Sheep

There were the sheep — Cotswolds, Hampshiredowns, Southdowns and certain other close-wooled breeds were exhibited; many of these being grade animals, if the classification may be judged by the records of pure-bred rams that were purchased by the leading sheep-raisers.

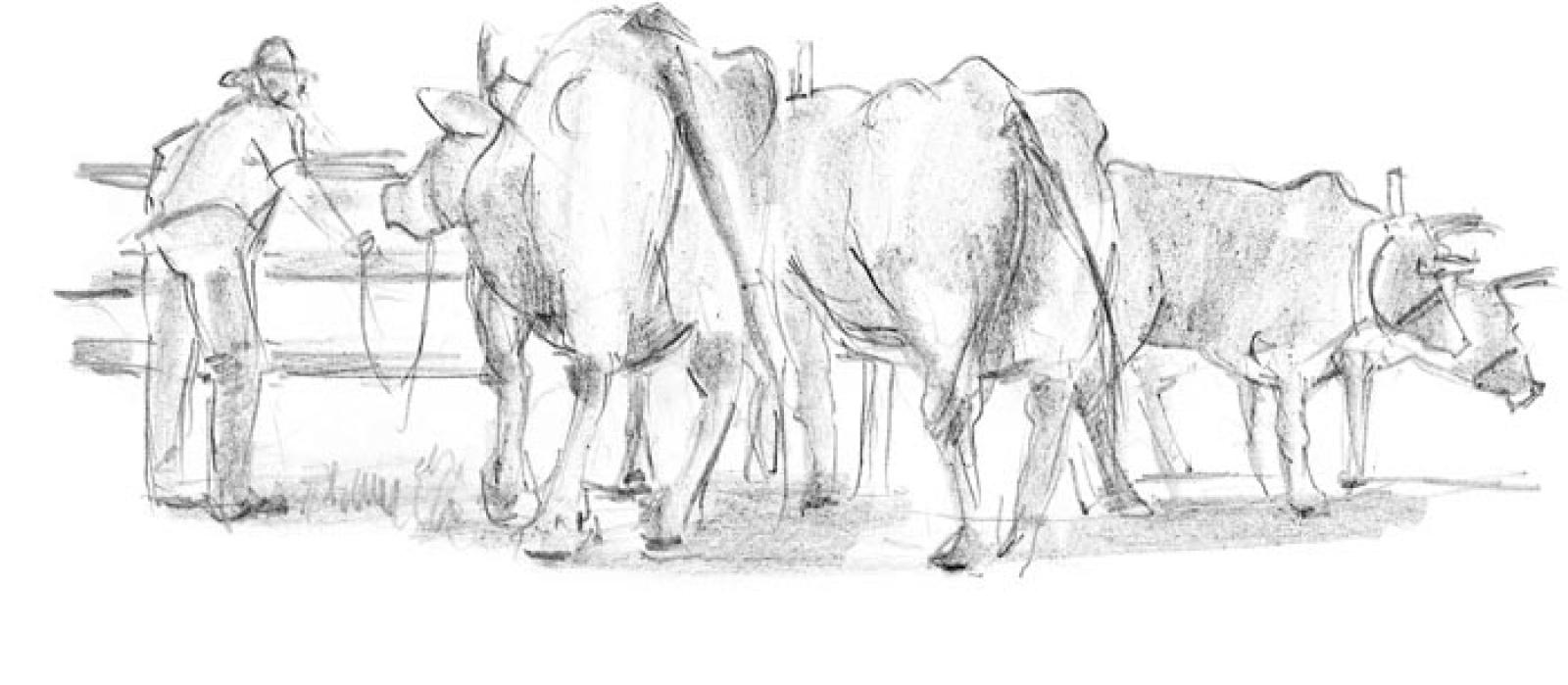

Oxen formed a prominent part of the livestock show, John Hammett driving seven yoke to the fair, according to tradition, John Davis, five yoke, Capt. Horatio Tilton, two yoke, and many others with two and three.

Mr. Hammett, aforementioned, did not drive his own cattle, but came to the fair in his carriage, a strange vehicle, with wooden perch-poles and leather springs, but something to admire in that day. His carriage, and a single-seated chaise owned by Henry Bradley of Tisbury, were the only two pleasure vehicles known to have been on the Island at that time. Undoubtedly there were others, but no tradition of them remains. However, it would have been strange indeed if Dr. Daniel Fisher had not possessed such a carriage, and there were others quite able to afford such luxuries.

Saddle horses lined the outside of the fence. Very few people of today realize how much horseback riding was done a century ago. And a word about the horses: there were few real draft-animals. Rather they were a light-weight, tough mixed breed, many of them raised on the Island, and quite probably crossed with the spotted Indian ponies of Gay Head.

Everyone Kept a Pig

Not so much is known of the exhibit of swine at that time. Everyone kept a pig or two and many had them in numbers, but somehow they received little mention in those early days. Probably it was difficult to transport a heavy hog to the fair in the beginning, but during the first quarter-century of the fair’s existence, some records were broken for heavy swine, some of them weighing more than five hundred pounds.

Sheep-dogs were present, but whether prizes were given for their points or performance is not known to this scrivener. But the farmers who drove their sheep to the fair were aided by the cross-bred “shepherds” owned throughout the Island in those days. Not as large as a collie and with yellow, or black-and-white coats, they were short-nosed and highly sagacious, and as handlers of sheep-flocks, they were all that man could desire.

The fruits of the harvest were numerous. Orchards dotted the Island, producing apples, pears, quinces, peaches and plums, and many of these found their way to the exhibition tables. Smith Mayhew brought wheat, carefully winnowed, and destined for the flour mills that turned on old Mill River. He also brought cranberries from his bogs, cleaned by leaving them in crates in a running brook.

There were bottles, filled with home-grown turnip-seed, and many exhibits of corn, particularly the heavy white ears favored for human consumption in that time. And William Case Manter brought samples of meal ground in his mill on Roaring Brook, also of clay pigment, for paint, more than a dozen natural colors, ground from the native clay.

Hand-Turned Bedposts

Josiah Mayhew raised hay, and took pride in the height of his seeded meadow-grass, “English hay,” as it was called, and possessed in quantity by few in those days. John Branscomb exhibited quinces, which he produced in great quantity, Allen Look brought potatoes, Capt. Granville Manter exhibited apples and walnuts, and Jacob Norton had crabapples and hand-turned bedposts, worked out on his own foot-powered lathe.

Products of the farm, the field, the pasture, the workshop and all other departments were welcomed, even as now, and there were more such to supply exhibits. The smoked ham and flitch of home-cured bacon had their places there. Cured fish may not have been exhibited, but sticks of cured herring and dried codfish were sold at the fair along with various other items.

They Wore Fancy Vests

The ruffled shirt-front, the starched collar that stood up to the cheekbones, the silk stock, several feet in length, and the fancy vest of glaring color and ornate buttons, were all a part of the really ritzy costume of the time.

This, of course, had nothing to do with the farm-hand or his employer, who had stock to care for and who wore homespun garments and cowhide boots or “brogans” secured by means of a buckle and strap across the instep.

Tales of those early fair-days contain but little mention of women. The handling of the fair was essentially a man’s job in that day, transportation was difficult indeed, and it may be assumed that the majority of those who went to the fair for any purpose, were men and boys of advanced age. There is but little evidence either for or against this sort of reasoning, and the conclusion may be wide of the mark, but there are indications that the social side of the fair did not arrive at its traditional peak until it had been in existence for some years. It was then that the music and dancing were introduced and the ladies welcomed in number.

But in that very early day there were so many things that did not survive. Apprentices of various trades were required to make something with their hands as evidence that they had mastered the “art and mystery” of the profession which they sought to follow. Iron and woodwork, for example, and pieces of furniture, fresh from the anvil or workbench, and which are no more.

Tale of a Mowing-Bee

Of those things which the younger men devised for sport and recreation there is little known. Such events were usually planned and executed on the spot, the result of argument and possible wagers. But the story has been told of a mowing-bee staged in a meadow near the fair ground, of heaving bluefish-jigs at a mark on the open field bordering Look’s Brook, lifting weights and shooting with a musket at a mark, or at the head of a turkey, confined in a crate from which his head and neck protruded.

Two brothers, with a shotgun which had one choked barrel, won sixteen turkeys in one shoot, according to the story. And although their opponents realized that there was something remarkable about the gun, they never discovered what it was. The cagey brothers offered it freely to the others, but they loaded it, and it was the open-bore barrel that they charged.

The picture has changed and changed again through the generations. Little by little, manufactured articles have replaced those made at home. The ox disappeared, gradually, it is true, giving place to the horse, and there came a time when the traditional Island pride in good livestock and fine crops declined. The exhibits revealed all this and the fair, as a farm and home exhibition, lost some of its attraction. Many stories of devious dealings have been told of this period and perhaps all of them were true. But the pendulum swung yet again, and again fine cattle and sheep were entered at the fair.

There is a lack of fruits, in these days, in the number of vegetable exhibits and there is no such number of animals on display as the older fairs knew. But it is pleasant to note that those things exhibited today are in keeping with the early tradition, the sort of things that might well bring a touch or pride to the original founders of a century ago.

Comments

Comment policy »