To unenlightened art history students Thomas Hart Benton is the champion of the heartland, a standard bearer for the Midwestern agrarian ideal. But a closer look at his paintings reveals the influence of an Island a world away.

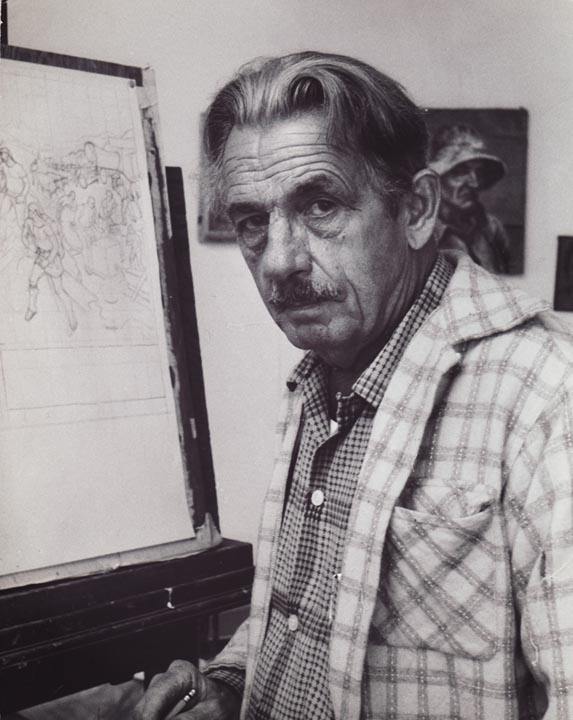

“It’s not just that Benton spent time on the Vineyard and not just that he loved the Vineyard, it’s that he really learned and developed his signature philosophy and artistic style from being on the Vineyard, and not from the Midwest,” said Justin Wolff, an art history professor at the University of Maine who has a recently-released book out about the artist titled Thomas Hart Benton: A Life.

Mr. Wolff will speak about the book at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum on Tuesday at 5:30 p.m.

In the book the author traces the life of this deeply contradictory and often controversial giant of American art, from a childhood spent under the disapproving eye of his state senator father, through an artistic career that saw him alternately cast as the darling and enfant terrible of the left, before being cast off altogether by an art world infatuated by abstract expressionism and pop art. And throughout his tumultuous career, the Vineyard served as both refuge and muse for the artist.

Educated in Paris and New York, it wasn’t until visiting the Island in 1920 that Mr. Benton developed his realist style, rooted in the land and the people who depend on it. While considered a founder of Regionalism, along with Iowan Grant Wood and Kansan John Stewart Curry, Mr. Benton’s instantly recognizable, muscular paintings owe less to the rural life and landscape of his native Missouri, Mr. Wolff contends, than to the scalloped, undulating cliffs of Aquinnah and the wizened Yankee farmers and fishermen of Chilmark, whom the artist once described as possessing the “nobility of medieval saints.”

“When he was living in New York he couldn’t quite figure out what to paint; he didn’t want to paint buildings or the people he knew,” said Mr. Wolff in a telephone interview with the Gazette this week. “Then he got to the Vineyard and he met what he saw as these heroic, hardworking fishermen and farmers. He was really moved by their stoicism and their ability to make a living on a rough land. It seemed to him to be this heroic deed that anyone could live there. ‘Aha,’ he said. ‘Now I’ve found the subject. Now I know what I want to paint, it’s these people who don’t brag, who don’t pretend to know more than they know. And what they know is useful. They know how to plow a field. They know where the fish are. But they don’t know anything about aesthetics or museums or art.’ ”

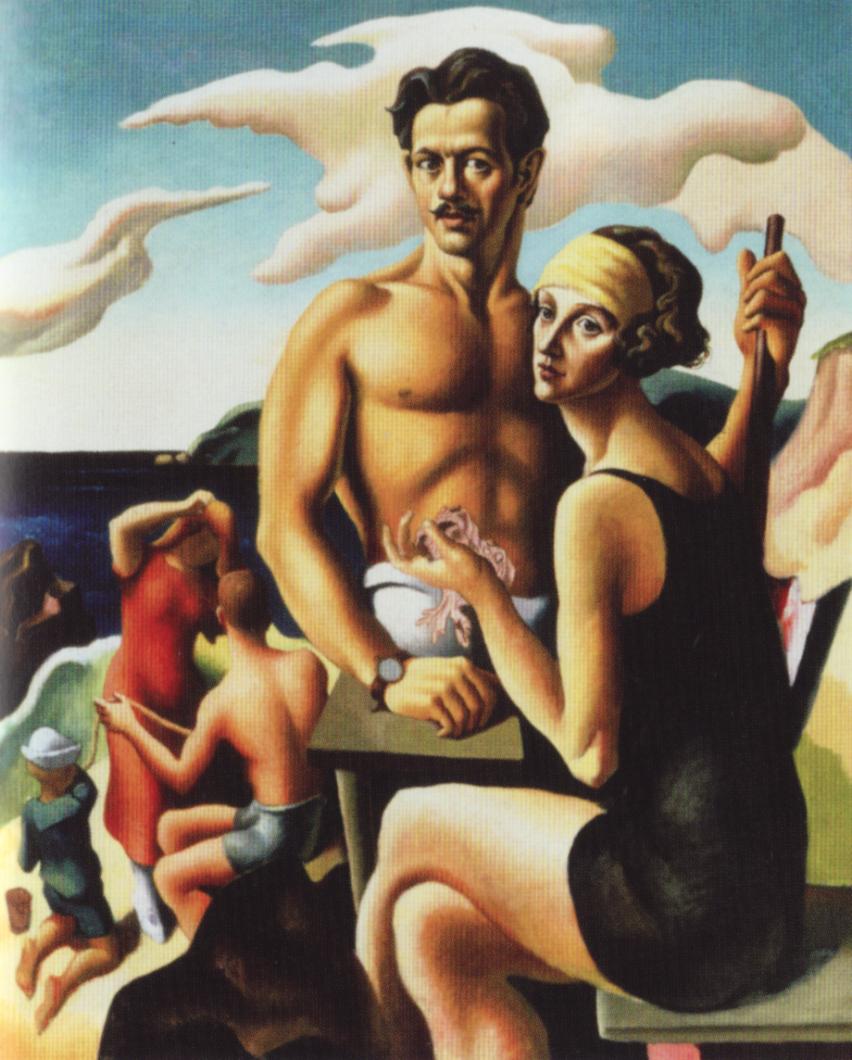

In 1922 he announced to the world this new anti-aesthetic aesthetic with a rather immodest self-portrait framed by the cliffs of Aquinnah and accompanied by his future wife Rita. Self-Portrait With Rita hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.

“When he went to the Vineyard it was the first time he ever really knew who he was,” said Mr. Wolff. “That painting is his way of saying, ‘Look, this is who I am’, and he announces it with real bravado and strength.”

Mr. Benton would continue to summer on the Vineyard for more than 50 years until his death in 1975. His social life on the Island continued to evolve over the decades, from sojourns at the Barn House in Chilmark where he nursed an anti-capitalist streak in the company of socialist newspaper writers and intellectuals, to languid evenings entertaining Alfred Eisenstadt, Max Eastman, Denys Wortman and James Cagney. Later in life Mr. Benton became close with the late 60 Minutes anchor Mike Wallace. But Mr. Wolff said the apparent contradiction between Mr. Benton’s association with the Vineyard and the glamorous intellectual set and his reputation as the spokesman for the working-class Midwest did not make the mission of his artistic life any less sincere.

“The conventional belief in artistic circles in Paris and New York where he had spent his early years was that art was made only for a privileged few — that is, there were a few sophisticated critics and other artists and philosophers who understood aesthetic language and that art was made for them,” Mr. Wolff said. “Benton felt that that was total hogwash. He just didn’t believe that, and I don’t either. Art is for everybody. Art belongs everywhere. And it can come from any kind of impulse. What he believed was that the best way to wrestle art away from these elitist institutions was to show average American folk having what he believed to be average American experiences. But through his painting style he would make those experiences important and even monumental.”

Author Justin Wolff’s talk about Thomas Hart Benton: A Life begins at 5:30 p.m. on Tuesday, June 5, at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum library in Edgartown. Admission is $8 for members and $12 for nonmembers. Books will be available for purchase and signing following the talk.

Comments

Comment policy »