It’s difficult to imagine today, but there was a time before resorthood on Martha’s Vineyard — a time before summer houses, before restaurants and shops and sportfishing and sailing, a time before people on the mainland even began to think that they might deserve a vacation every once in awhile on a pretty Island far from home. But on the Vineyard, the pre-recreational era wasn’t that far back — 160 years ago at the most.

The man who publicly teed up the whole idea of Martha’s Vineyard as a vacationland was Edgar Marchant, who founded the Vineyard Gazette in 1846. An exhorter for causes and a squabbler in politics without any known rival in the annals of Island history, he campaigned for the idea of the Island as a resort in edition after edition.

“The Vineyard as a Watering-Place in the Summer Season,” read a bold headline on Oct. 7, 1847. Under it Edgar Marchant urged his fellow Islanders to start thinking about how the place might appeal to those with a little extra time and money on their hands.

To vacationers, he wrote, the Island offered views of open fields with “large droves of sheep basking in the sunshine,” miles of beaches, pleasant cottages and long drives over country roads. Time spent on the Vineyard would revive the invalid visitor and charm the vigorous. And for the sportsman especially, he wrote, “Here we have something besides black-fish or tautog; from the blue-fish, perch and striped bass, to the bonito and sword-fish, with numerous other kinds, sufficient to give the most athletic, or dyspeptic personage an appetite for breakfast, should he start at the proper time, prepared for the business.”

But while whaling thrived over the course of the next 15 years, nobody on Martha’s Vineyard took up the novel Marchant quest for resorthood in any organized way. Only at the start of the Civil War did Islanders and mainlanders begin to see and feel how the Vineyard might appeal to those who could afford to visit and enjoy it.

This was the period when the famous Methodist revival meetings on the highlands of the future Oak Bluffs began to attract the first summer visitors who were thrilled by the charismatic preaching and praying on the Camp Ground — and who also seized the chance to break away now and then to enjoy walks over the nearby forested hills and visits to the sea and Sound.

At the same time, Islanders and mainlanders who were actually attending the religious meetings found themselves edging upward into the ranks of a new middle class, and they began to set up their tents or open their Camp Ground cottages a week or so before the meeting and stay longer and longer afterward. These were all the first vacationers on the Island of Martha’s Vineyard. And as whaling faded away as an industry, the pathway to a reliable, if seasonal, prosperity looked clear enough.

But only the most vigorous Island entrepreneurs appeared to answer the call to resorthood. With nearly the same intensity of pleading and petulance as Edgar Marchant, editor James M. Cooms of the Gazette railed at Vineyarders for what he saw as a failure to organize the businesses and promotional campaigns that would elevate the Island into the ranks of leading summer retreats.

“How opens the [year] on the island?” he wrote in early 1866: “Are the prospects flattering? Are the interests of capital and labor being looked after and developed for its consequent prosperity? Quite the contrary. Pecuniary selfishness and enervated energies bars business enterprise, and jealousness thwarts every successful effort towards its prosperity.”

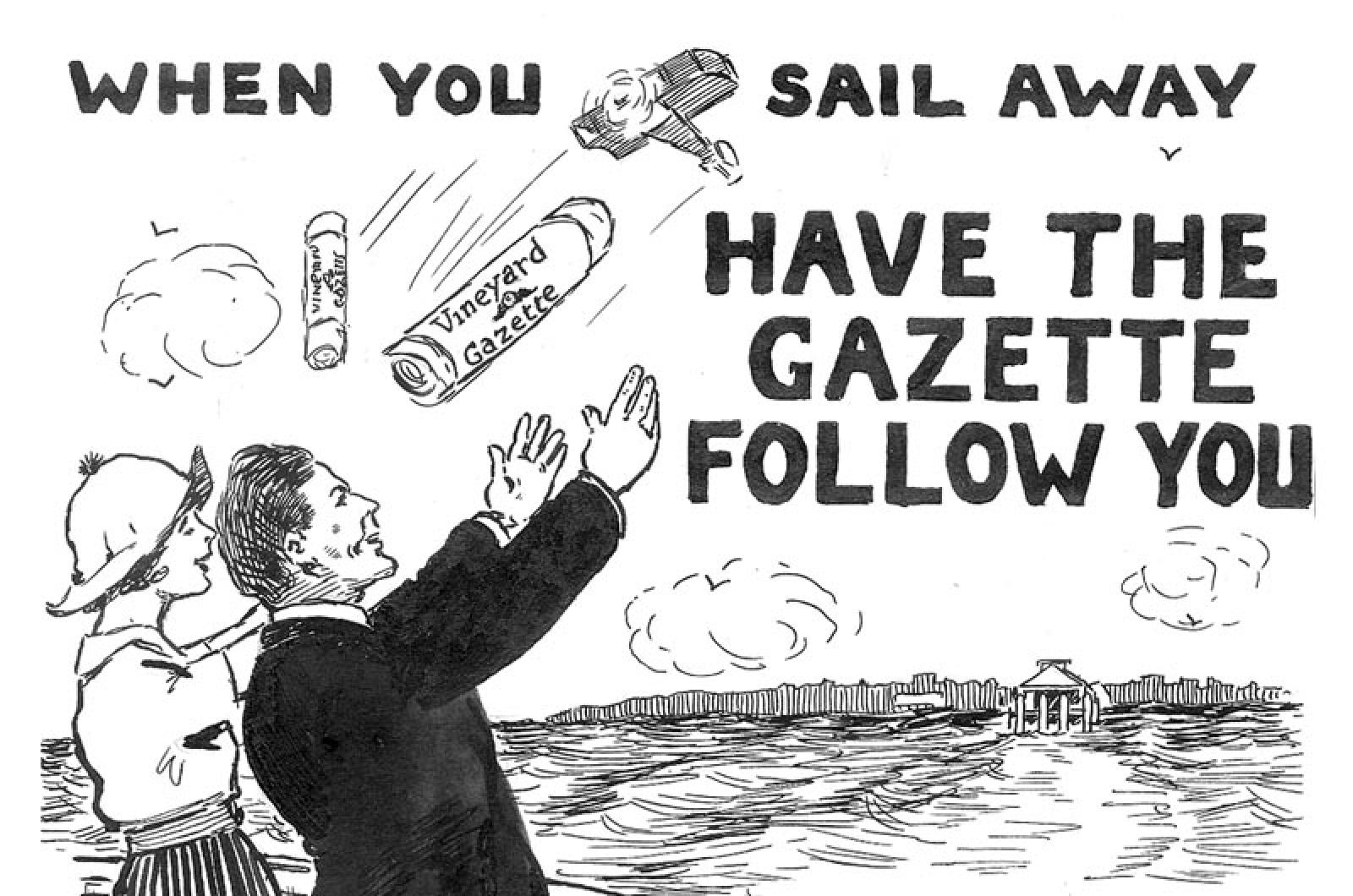

For the 30 or 40 years that followed the postwar boom of the late 1860s and early 1870s, the Island suffered through more years of recession than prosperity, except in the vigorous new seaside resort of Cottage City, now Oak Bluffs, which soon encircled the Camp Ground. The Gazette, with few readers on the mainland, could not advertise the charms of the Island by itself, and it alternated between appealing to its business owners to do more to lure vacationers here and lamenting the general state of stagnation.

Then in the spring of 1933, when the Depression was biting deep, the Gazette tried something daring and new. That spring and early summer, editors Henry Beetle Hough and Elizabeth Bowie Hough launched back-to-back special annual editions, the Invitation and Directory, expressly designed to draw a growing mainland readership to the Island for the summer and guide them while the visitors were here.

“Martha’s Vineyard is within reach of the whole country,” the first Invitation Edition said. “Yet it represents an utter change of atmosphere and scene. It would be possible to travel thousands of miles without finding a spot so different from the populous parts of the United States and so completely unspoiled.” But even during those hard times, when every visitor counted, the editors were aware that selling the Island could wreck what made it appealing.

In 1930 the paper said: “There is no doubt that new thousands of people will wish to come here in the next few years, and it is as well to bear in mind that a point of diminishing returns exists beyond which the Island will begin to lose instead of gaining. If we will not mishandle our destiny entirely, we must treat conservation as of equal importance with development; the open spaces must not be too closely built up, the trees must not be cut away, the roadsides must not be mutilated, and the attractions which bring welcome visitors must not be lost.”

Beginning in the late 1960s — as fame and notoriety lit up the Island in single-word detonations (Chappaquiddick, Jaws, Onassis, Clinton, Diana, Obama) — the Gazette found itself managing what its critics called conflicting and even hypocritical motives: how to argue with logic and passion for the preservation of a unique offshore world while also carrying the ads and publishing the stories that helped to draw more and more people to these shores.

To the Gazette, the answer was plain then and now: In a resort economy, visitors are needed and wanted. But the more they know about the Vineyard, the more they commit to it, care for it and share in the values that Gazette stories describe and the most thoughtful advertising promotes. In 1990, as neo-suburban developments were cutting up the landscape, editor and co-publisher Richard Reston described a fundamental change of mission behind the Invitation Edition, reflecting the philosophy of the paper as a whole.

“Fifty years ago the times and circumstances allowed, perhaps required, the Gazette to spread its invitation message to all, especially to newcomers who had not yet heard of the Vineyard, who had not yet experienced the special qualities of life on the Island,” he wrote.

“This is not the case today. The Gazette is not trying to reach more and more people, more and more newcomers. We are in a sense writing more to ourselves, more to people who already know the Vineyard and its community of people. The message now is about a different kind of need, a new sort of struggle facing the Island and its future. The Gazette today is arguing for more quality of thought, for more caution about the Island’s future, for open public dialogue, for more exploration and bold approaches that may offer ways to protect and preserve the natural resources of the Island.”

After all, if the Vineyard lost the people, things and landscapes that made it different from anywhere else, then anywhere else would be the place most visitors would find it more easy and inexpensive to go.

Comments

Comment policy »