The old Luce Cemetery on the shore of Noman’s Land is at risk of being washed into the sea, and some of the graves may need to be moved farther inland, a representative from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said this week.

Elizabeth Herland, eastern refuge manager for the fish and wildlife service, began working last summer on a proposal to begin reconnaissance at the cemetery, and soon realized that erosion was happening faster than anticipated.

The federal service is now working with state and local officials and a private archaeology company to determine whether there are, in fact, burials at the site.

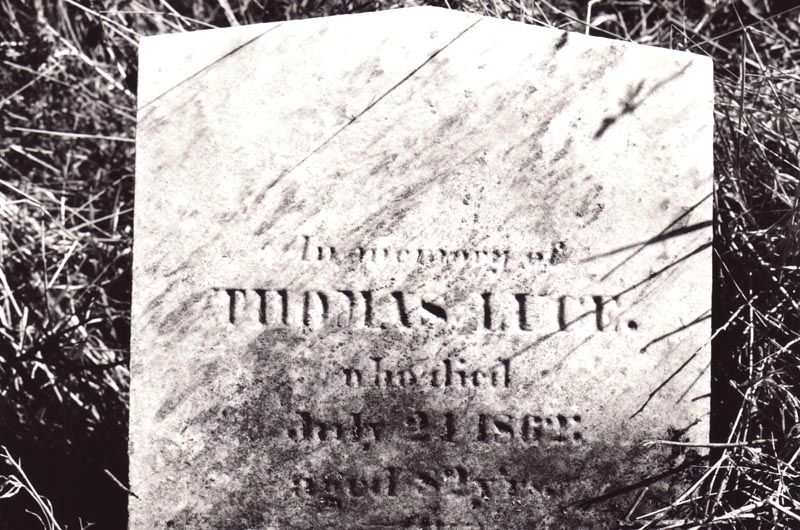

The one inscribed headstone is that of Thomas Luce, who died in 1862. Records at the Gazette show that Mr. Luce’s father, Israel Luce, who died in 1797, is also buried on the small island that lies three miles south of Squibnocket. Ms. Herland is hoping that descendants of the Luce family will come forward with information they have about who might be buried in the cemetery.

Buddy Vanderhoop, a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and owner of Tomahawk Charters, out of Menemsha, recently brought a group of researchers to Noman’s. He described a scene where bones were protruding from the ground. “It was just a few bones, but they were human,” Mr. Vanderhoop said. He added that several graves were marked with both head and foot stones, indicating a Native American burial ground.

Ms. Herland emphasized this week that reports of human remains being found at the site have not been confirmed.

The island has a long history of human habitation. In the mid 1700s it was home to a number of sheep farmers, and a group of about 60 codfishing families would pass through in the summer and fall until codfishing declined in the late 1800s. It was also a rendezvous point for rum runners during prohibition in the 1920s.

During one gruesome incident, everyone aboard the John Dwight, a steamer out of Newport that was carrying barrels of ale, was murdered. As recounted in a 2011 story in the Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, the Coast Guard recovered nine bodies and destroyed the ship. Bertrand Wood, who lived on Noman’s Land and whose great-grandfather was Israel Luce, wrote that several other bodies had drifted ashore and were buried in the cemetery.

The island was used as a bombing range by the Navy beginning in the 1940s and is now closed to the public. Mr. Vanderhoop’s charter group was joined by a specialist who carried a magnetometer to detect any unexploded ordnance below the surface.

A story published in the Gazette on Sept. 23, 1949 expressed concern over the bombing, stating that “there was, and perhaps still is, a burying ground on Noman’s Land. There are probably few people who know of this and fewer still who know where it is. It is even more probable that no one living today knows how many graves there may be in this desolate plot, or who could mention more than two or three names of the people who lie buried there.” The story also said:

“Records pertaining to Noman’s Land are unsatisfactory, to say the least, traditions are many, and while the majority of them appear to be without foundation or fact, there is probably some ground for them. But the burying ground is or was there, containing the bones of people who made their homes on the island, very probably certain Indians, and the bodies of victims of shipwreck in days of long ago.”

If burials in the area nearest the shore are confirmed, the fish and wildlife service will work with state and local groups to move them farther inland.

“We believe that they are native American burials, but that has not been confirmed, and it won’t be confirmed until we actually do the archeological work,” Ms. Herland said. That work has not been scheduled, but she expected it would begin this winter or spring. “Even though it hasn’t been the best conditions, we are trying not to postpone it,” she said.

A longer-term study of the cemetery area is also being planned. “Right now our thinking is, over time the entire cemetery will be relocated,” Ms. Herland said.

The fish and wildlife service is also working with the Massachusetts Historical Commission and the Chilmark Historical Commission, and will likely contract with Public Archaeology Lab (PAL) of Pawtucket, R.I. PAL recently surveyed the area surrounding the Gay Head Light in Aquinnah, which is expected to be relocated this spring, also in response to coastal erosion.

Information about the cemetery may be emailed to Ms. Herland at libby_herland@fws.gov.

Comments

Comment policy »