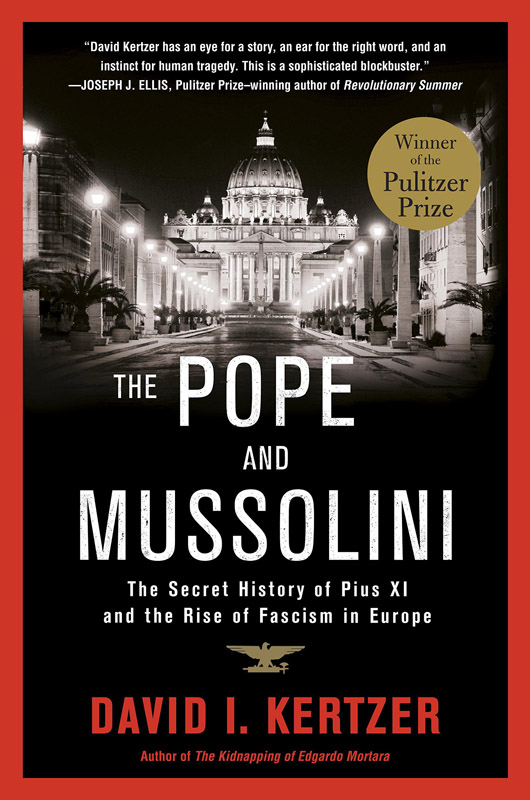

Benito Mussolini is long gone, but the institution that helped bring him and keep him in power may not be, according to a new Pulitzer Prize winning book by historian and Brown University professor David Kertzer. Mr. Kertzer’s book, The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe, revisits the narrative of a courageous Catholic Church fighting against a tyrannical fascist regime, and finds that, instead, both institutions were helping each other gain a tighter grip over Italian society.

“The key ingredient to Mussolini really becoming a dictator was the Church,” Mr. Kertzer told the Gazette. “Without it, it wouldn’t have happened. Or it could have been stopped.”

The author will discuss his work at the Martha’s Vineyard Book Festival on Saturday at 1:30 p.m. at the Harbor View Hotel, and on Sunday at 12:15 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center.

The book focuses on Mussolini, who first came to power after the March on Rome in October 1922, and on Pope Pius XI, who ascended to the Papacy in February of the same year. While the book does delve into the rise of fascism and the church’s return to prominence in Italy, it is mainly framed as a biography, focusing on the personal and political story of these two men.

“Both [Mussolini and the Pope] came to power early and had terrible tempers, and were well known for it among their subordinates,” Mr. Kertzer said. “But they also came to depend on one another, in a sense.”

It was, after all, the Pope’s support of Mussolini following his ascent to power that allowed the dictator to remain in control during crises like the murder of opposition leader Giacomo Matteotti in 1924, according to Mr. Kertzer.

Yet the Pope, he is clear to point out, was not simply acting out of a love for the fascist doctrines Mussolini espoused. The fascist government provided the Vatican with new rights and privileges that had previously been constrained due to its unstable status in modern Italy.

Mussolini not only reinstated the Church’s status by allowing for the sovereign state of Vatican City within Rome but also made Catholicism the official state religion, elevating the Catholic Church to an important position within the fascist state.

“People tend to think of Nazi Germany when they think of fascism, but here it is actually quite different,” said Mr. Kertzer. “The church was incorporated into the state under Mussolini, whereas Hitler tried to sideline the Catholic Church in Germany.”

While the Pope may have experienced some bond and connection with Mussolini, he certainly felt no affection for the German leader to his north, according to Mr. Kertzer. Witnessing what Catholic cardinals had to endure under the Nazi regime and recognizing that unlike Mussolini, Hitler did not want the church to play any role in the new society he wished to create, the Pope frequently urged the Italian leader to abandon any attempt to forge ties with the German nation.

“One of the things I found as I was going through these archives is almost this continuous stream of requests for [Mussolini] to intervene against Hitler,” Mr. Kertzer said. “Hitler was seen as anti-religious and highly anti-Semitic, far more so than any amount of anti-Semitism that the Pope had previously espoused.”

This is not to say, however, that the Church was clean of anti-Semitic or undemocratic beliefs. In fact, Mr. Kertzer argues that the fascist regimes of the era were in many ways executing what the church had been preaching for years.

“The Vatican really had created an environment of anti-semitism and authoritarianism,” said Mr. Kertzer. “Which included warning against Jewish influence and the need to restrain it.”

Pope Pius XI was especially notable for this, having spent time in Poland following the Russian revolution and developing an extreme wariness of both communism and Jews.

But while Italian fascism did shun communism, it may not have begun as an entirely anti-semitic crusade. Mr. Kertzer noted that, proportionally speaking, there were just as many Jews as Catholics in the National Fascist Party as late as the early 1930s. But that did not stop restrictions and laws against Jews coming into effect in 1938.

“For him, it wasn’t as much of a concern as the protection of the church and his own cardinals,” said Mr. Kertzer. “Both in Italy and Germany, that was the concern.”

Toward the end of his life, Pope Pius XI tried to recant at least some of his support for Mussolini and his government. But by then it was already too late. The Pope died one day before he was scheduled to deliver a speech to the all the bishops in Italy denouncing Hitler and Mussolini’s relationship, and with him also died the speech. Its text was in fact destroyed by the very man who would succeed him as Pope Pius XII.

Much of this information comes from recently released Vatican archives Mr. Kertzer was able to access, a source that he claims was indispensable to understanding the entire story of the church’s relationship with the Italian dictator, both good and bad. But it also meant upending a typically established narrative of the history of fascism and religion that permeates much of contemporary thought both inside and outside the walls of the Vatican.

Nevertheless, Mr. Kertzer has asserted the importance of recognizing the sometimes troubling history that marks the era, especially given the possible resurgence of neo-fascism at a time of economic and political crisis across Europe.

“I don’t want to sound holier than thou,” he said. “But we do have to recognize this history, and we have to come to terms with it.”

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »