Just north of the town center in West Tisbury, the historic Parsonage House floats eerily above its new foundation, surrounded by construction equipment and debris. Rusty steel beams on wooden blocks run through the windows, holding the house aloft until work resumes this spring.

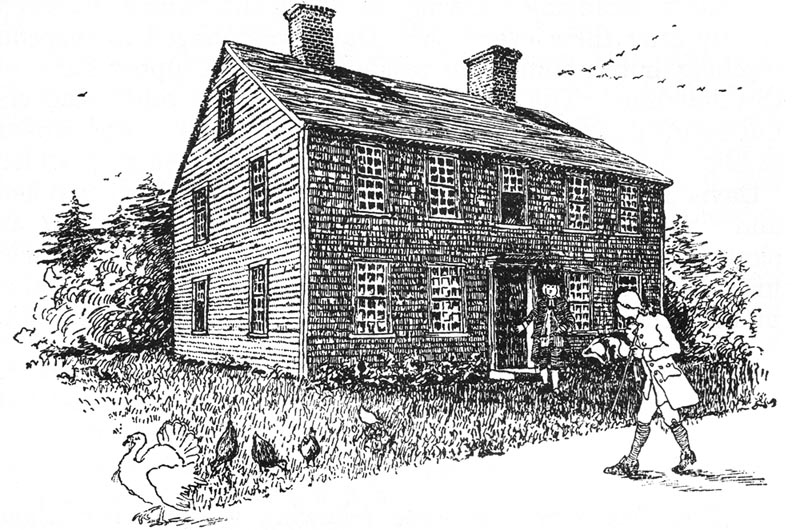

Sean Conley, a member of the town historic commission, which approved the restoration project last year, stepped out of his truck and stood at the edge of the property. As is often the case with historic preservation, the house will not return to its original state — a 17th-century cottage — but to a much later period, preserving both the original structure and two centuries of change.

“It’s going to look like the 1880s Victorian with the diamond windows in front like it had originally,” Mr. Conley said of the 1.5-story, L-shaped house overlooking fields and a small wetland. “Everything is going to look exactly the same as it was.”

In each of the Island’s four historic districts — in West Tisbury, Edgartown, Vineyard Haven and Oak Bluffs — the sounds of construction and the sight of bare lumber usher in a new season. It’s a familiar rhythm across the Island, where visitors and residents alike enjoy some of the most varied and well-preserved architecture in the country.

Some 2,000 buildings on the Vineyard predate the early modern period, beginning in 1915, including about 930 within the historic districts and many rare examples of 17th century architecture. An afternoon stroll through Edgartown or West Tisbury might reveal two or three centuries of architectural history.

Christopher Scott, director of the Martha’s Vineyard Preservation Trust, which maintains 21 historic structures and four historic landscapes around the Island, said a combination of natural and historic qualities have long been what draw people to the Vineyard.

“What distinguishes our towns from Anywhere Else, USA, is the history and the intactness of our architecture,” he said, largely crediting the thousands of homeowners who have invested in historic preservation over the years. But at the same time, others said, an improving real estate market has ratcheted up the pressure to preserve the Vineyard’s historic homes.

The West Tisbury historic district was formed in 1982 with strong support from the community. At the time, it included 14 properties around Mill Brook, the original town center. But on the heels of a housing boom in the 1990s, concerns grew and in 2000 the district was expanded to include about 110 houses fanning out from the town center.

“It’s a continual balance of the rights of the individual versus the rights of the community,” said Mr. Conley, a real estate broker who joined the commission in 1986. But he said few projects have strayed from the overall town character. “In my 30 years, I think we’ve denied two permits,” he said.

It’s a similar situation in Edgartown, Oak Bluffs and Vineyard Haven, where voters also approved historic districts, starting with Vineyard Haven in 1975. Each bylaw is tailored to the community, but follows state and national guidelines developed since the 1960s.

“Everyone is mostly interested in preserving their property,” said Carole Berger, who has served on the Edgartown historic district commission for more than a decade. As with the other towns, the commission oversees repairs, renovations and additions, with an eye toward preserving the character of the neighborhood. But historic preservation remains highly subjective. Not everyone agrees with it, while some wish the commissions had more power.

Edith Blake, who serves on the commission and began planning for the Edgartown district in 1972 with a small group that included her husband, the late Gazette publisher and editor Henry Beetle Hough, saw the efforts as only partly effective.

“We’ve had some very bad things arrive in town, and it’s not pretty,” she said this week. “There is such a thing as scale, and if you get a house that’s too big for the scale it looks awful.”

The originally proposed district included the village from Edgartown harbor north to around Pease’s Point Way. Those plans were scuttled by opponents, Mrs. Blake said, and a smaller version was approved years later. At the annual town meeting in two weeks, Edgartown voters will decide whether to expand the district to include much more of the town center, where styles range from early Capes to 19th-century Greek Revival and modern beach houses.

Some see historic preservation on the Island as aesthetic concerns taken too far. Michael Horvitz, who bought a house on Starbuck’s Neck, just outside the Edgartown district in the 1990s, was glad not to have the extra layer of review when he demolished the early 20th-century house and built a new one in its place.

“It was just not suited to a modern life,” he said of the earlier house. Among other things, a zoning rule that prevented new construction within 100 feet of the water limited the options. “We spent about six months trying to figure out what we could do to try to straighten it out,” Mr. Horvitz said. “We finally decided, if we tear the house down and we move the footprint back 10 feet we can actually do what we want.”

He continued: “We tore the house down and we built what we think is a house that’s very compatible with the neighborhood and the style of these houses, and I think people going by would have a hard time concluding that it’s not an original house. Frankly, I think it’s much more attractive than the house that we tore down.”

At around 8,000 square feet, the house is also larger than the original, but Mr. Horvitz believes it more closely resembles others in the neighborhood.

Many would agree that change is inevitable, and even desirable. Mrs. Blake recounted some of the changes that have occurred in Edgartown, sometimes as a result of historic preservation. In the distant past, she said, no one could afford picket fences, and Islanders made their own paint using whatever pigments were available. Old houses often had no cellars, and were easier to relocate. “They were moved all over like a chessboard,” she said.

The Greek Revival in the 1800s left a heavy mark on Island architecture, with a large number of stately white buildings with gable roofs visible from Edgartown to Chilmark. Not only were they built to last, but some say they set in motion the tradition of using white paint that remains today.

In Vineyard Haven’s William street historic district, change itself is considered part of the fabric of the neighborhood. Among other things, the bylaw specifies that additions, renovations and outbuildings more than 50 years old are also significant. But all historic districts focus on preserving the original edifice, as visible from a public way.

Mark London, former director of the Martha’s Vineyard Commission who has a background in historic preservation, noted the Island’s remarkable natural heritage, which he believes has often taken precedence over an equally remarkable building heritage. “We’ve done a reasonably good job protecting it,” he said of the latter, although he believed conservation efforts were far more organized.

Until the 1970s, historic preservation on the Island was mainly a byproduct of simpler lifestyles and a tendency to reuse what was there, several longtime Islanders said this week. The practice is evident across the Vineyard, where antique houses are as much a part of the landscape as the surrounding oaks and cedars.

“People today are still living in them, still loving them, still cherishing them and still maintaining them,” said Jonathan Scott, an architectural historian at Castleton University in Vermont and an authority on early Vineyard architecture. “Over the course of many generations, the houses have been changed. They have been altered to suit living conditions of the time. The good thing is, the basic house has been allowed to survive.”

Even new houses on the Vineyard may incorporate historic materials as a result of the tendency to reuse.

Clarence A. (Trip) Barnes 3rd, who owns a moving company in Vineyard Haven, said many of the historic building materials he has collected over the years have ended up as features in his friends’ houses. “They like the old,” he said. “And that’s what I’ve always felt. I can put a house together you would swear was 100 years old and it’s not.”

Mr. Barnes also serves on the board of the preservation trust, and helped renovate the Grange Hall in West Tisbury, which the trust acquired in 1997. He was especially fond of its rough-hewn floorboards and old-fashioned charm. “It’s just good taste,” he said. “The older it gets the better it’ll look.”

A growing concern for historic places nationwide led to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the state and federal guidelines that now underlie historic preservation efforts across the country. But in some ways the Vineyard was ahead of the curve.

At the time, Mr. London was advocating for historic preservation in Montreal, which was also somewhat ahead of the curve. He said part of what defines the Vineyard landscape, apart from its natural heritage, is the willingness of Islanders to continue building in traditional styles, even as national trends come and go.

He noted the presence of poorly conceived “historical-ish” houses, and the occasional mishmash of styles on the Vineyard, but disagreed with purists who believe that new buildings should have modern styles to avoid muddling the historic record. He even credited some of the Island’s best characteristics to new construction.

“If every building in downtown Edgartown since 1950 had been built as a modern-style building, you would not have the Edgartown that people love,” he said.

He also drew a line between “museum pieces” and neighborhoods where people still live. “If you’re dealing with lived-in communities that change and evolve over time — to me, you don’t have to take that very precious approach,” he said.

The Cottage City historic district in Oak Bluffs has some of the most particular building guidelines on the Island, aimed at seamlessly blending old and new. The district commission oversees most of the houses east of Circuit avenue, which feature such ornate styles as Queen Anne, Italianate and Gothic Revival. Guidelines include painted wood trim “with contrasting textures and decorative detailing,” such as lap siding, shoulder casework, cornices and brackets. Painted wood porches, double doors and historically pitched roofs are also recommended. As with the other towns, however, the commission now allows synthetic wood in some cases.

Bricque Garber, assistant to the Edgartown historic district commission, said the key in her town was to balance preservation and building requirements with the demands of modern life.

“What we are looking at is preserving the historical integrity of the village and still allowing people to make renovations and do what they need to do to their homes so they are comfortable,” she said. The district has no control over square footage, she added, but focuses instead on the shape and appearance of structures.

Several years ago, the commission forced the Federated Church on South Summer street to remove newly-installed vinyl siding. And it recently denied a demolition permit to the owners of 8 Pease’s Point Way, who have taken their plans for a new house to court. But applications are rarely denied, Ms. Garber said. The same is true for William street, where several major renovations are underway. Resident Michael Levandowski described what he sees as a renaissance of historic preservation in the district, which is dominated by the 19th-century homes of sea captains and other maritime figures, and small front yards. “There’s a lot of value in that community,” he said. Among other things, he cited the area’s growing popularity on Halloween, when kids from on and off the Island swarm the neighborhood. “We alone had over 1,000 children last year,” he said.

Mr. Levandowski was a member of the town historic district commission three years ago when he and his wife, April, renovated two historic houses on William street, one of which they plan to use in retirement. The process went smoothly, since they knew what to expect, Mr. Levandowski said, but the commission is generally open to modern upgrades such as solar panels or composite shutters.

He said about half the street is occupied year-round, and the homes are generally less expensive than historic homes in Edgartown, most of which are vacant in the winter. William street has the benefit of being near the town center, he added, where many businesses remainopen year-round. “People want that sort of lifestyle,” he said. “It’s basically living in a city, in Martha’s Vineyard, or as close as that can be.”

Many, if not most, historic homes on the Island are owned by seasonal residents, whom Christopher Scott largely credited with an uptick in historic renovation in the last 10 years. He added that seasonal residents benefit the year-round community through increased business and philanthropy. “They are making an investment in their enjoyment,” he said. “But they are investing in the place, which benefits all of us.”

The economics of historic preservation on the Vineyard has yet to be studied, although some benefits are clear. Mr. Scott estimated that the preservation trust properties draw more than a million visitors each year, with financial benefits across the Island. And a number of nonprofits make use of the Grange Hall throughout the year. “They don’t have the resources to be in the old-building business, but that’s our job,” Mr. Scott said. “What they do is they enrich the community through their activities. So it’s a great arrangement.”

Mr. London noted that property values are typically much higher in historic districts. “You know that the investment you’re putting into your property is not going to be undermined because the person across the street is going to build some horrible monstrosity,” he said. “You are all mutually protected.”

But others weigh the costs and benefits differently. Mrs. Berger pointed out that while people tend to take care of their historic homes, “you can certainly buy more house outside the district, in square footage.” And Mr. Horvitz argued that pushback against the proposed expansion in Edgartown would artificially depress property values in that area.

Mr. Scott agreed that historic preservation hasn’t been perfect, and he understood the resistance to change. But he said the Island was ahead of most other communities in the country, in both planning and practice.

“People don’t like it, but change happens every day,” he said. “And it has every day in history.” Looking forward, he believed that regulatory bodies and nonprofits, along with a sense of commitment, would continue to preserve the Island character. “All of it working together, I think, manages change in the best possible way.”

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »