The island was tiny. As we sailed closer, we smelled the sweet aroma of land. We saw a crowd on the beach. Then the singing reached us — a soft, undulating sound blending with surf and wind. Outrigger canoes paddled out to us as we anchored our chartered ketch. We seemed to have stepped back in time hundreds of years. This is Satawal — in the Caroline Islands — a place where an ancient way of seafaring and navigating, lost almost everywhere else, has persisted.

The year is 1982, and I have come to make a film about the great Polynesian settlement of the Pacific. Science tells us that Hawaiians, Tahitians and the New Zealand Maori are one people, and that they found their way across thousands of miles of ocean to settle those widely scattered islands. They were able to build, equip, man and navigate vessels large enough and seaworthy enough to make passages of up to 2,500 miles. Descended from the same ancestors as the Polynesians, the people of Satawal still build sea-going outrigger canoes, man them with sailors, and navigate them throughout their widely scattered islands without maps or instruments of any kind.

We are a crew of five: Boyd Estus, director/cameraman; Roger Haydock assistant cameraman; Eric Taylor, sound man; Sheila Curran Bernard, associate producer. I will produce, write and co-direct the film, to be titled The Navigators — Pathfinders of the Pacific, for broadcast on PBS.

Satawal’s isolation, and that of the other Caroline Islands, accounts for the preservation of a seafaring life unknown elsewhere. Along the island’s sheltered shore, outrigger canoes are drawn up beneath lofty canoe houses open on all sides. Their thatch roofs glisten in the sun. The floors are covered with fresh palm fronds and woven mats for lounging or sleeping. We have come here to live and sail with Mau Piailug — one the last handful of traditional navigators.

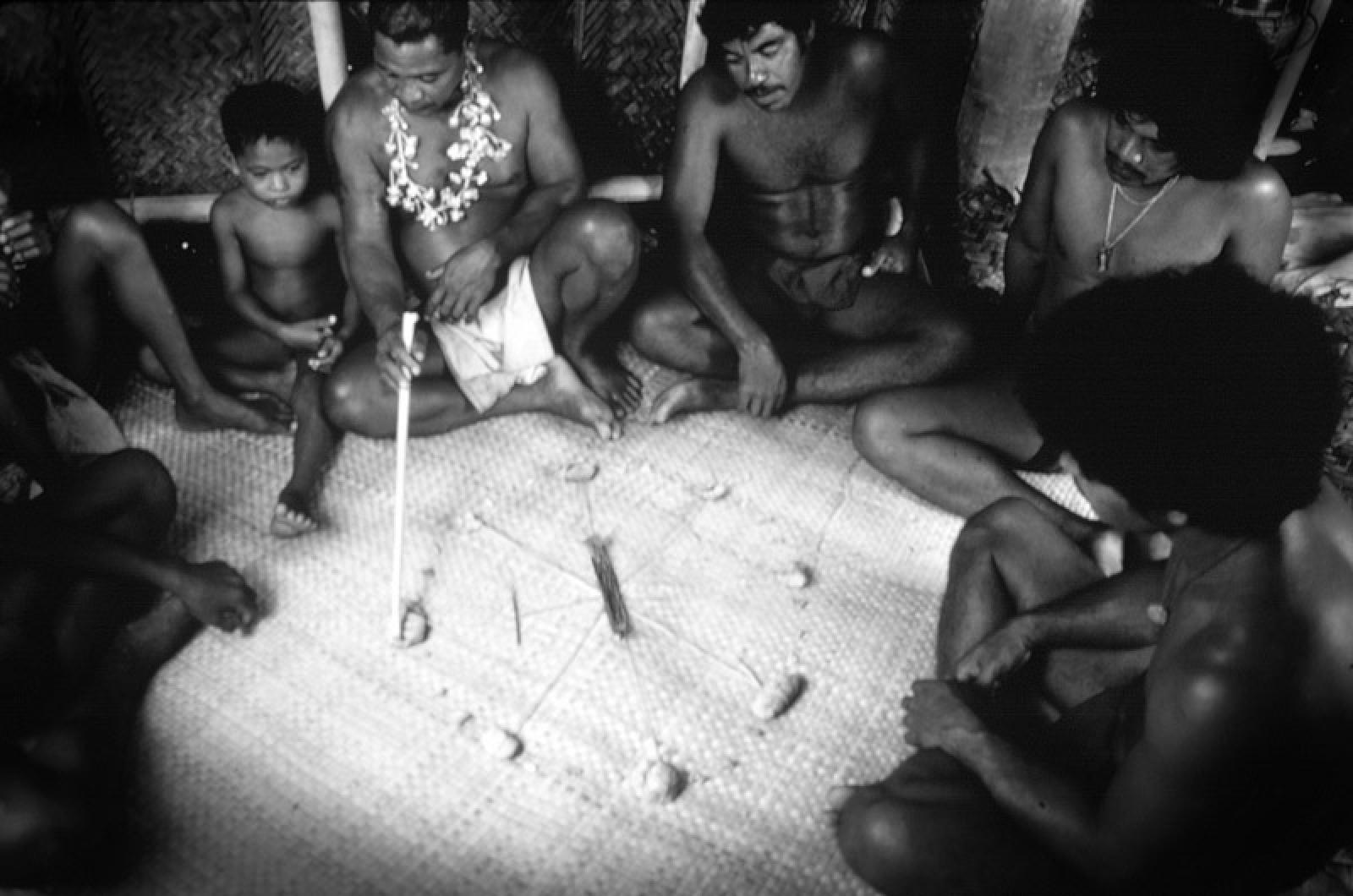

To show us and our audience how he finds direction at sea, Mau brought his students together in his canoe house where he laid out a woven mat — a teaching device, a representation of his star compass. He placed 32 lumps of coral in a circle to represent the rising and setting points of the stars he steered by. He chanted softly, his students repeating after him: “This is Mailap, it rises in the east and sets in the west. Here is Tumur . . . .”

He placed a model of his canoe — made with sticks and palm fronds — on the mat. And with other fronds he simulated the waves that rocked the canoe, coming from different directions. He finds his way by them on nights when clouds obscured the sky.

Later he took us to sea and pointed out the stars — a heads-up display of direction more accurate for steering than any magnetic compass. And by day we filmed on his canoe as he taught his students to recognize the swells by sight and by the motion they imparted to the canoe.

We captured scenes in the canoe house as his men built a canoe. We watched in wonder as they carved planks with an adze to exact shapes and fitted them to the hull. Then they warmed breadfruit sap over a fire and applied it to the seams, along with caulking carved from the outer shell of a coconut, to make the canoe watertight. In another part of the canoe house, men wove rope lashings from coconut fiber that they used to sew the planks together. Everything needed to make such vessels was harvested on Satawal. An ancient shipbuilding technology was coming to life before our lens. Still later during our filming odyssey, on the Tahitian island of Huahine, we recorded archeologists excavating huge planks that bore the same signs of lashings as the canoe on Satawal — confirming the antiquity of this expertise.

Finally, in our editing room in Cambridge, we wove the scenes together with footage of archeologists working in Fiji, Huahine and Hawaii — tracing the paths of the earliest Polynesians from islands off New Guinea to Tahiti and then in long arcs to the furthest reaches of the Polynesian triangle — to New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island. We included images of men chanting ancient songs as they worked, expressing the deep ethos of their seafaring culture.

We added footage shot by the National Geographic Society in 1976, when Mau put his navigational abilities to the ultimate test by guiding a replica of an ancient Polynesian canoe named Hokule’a from Hawaii to Tahiti. Without charts or instruments of any kind, using only a map that exited in his mind and sailing by the stars, swells and flight of birds as guides, he was the first to demonstrate his wayfinding abilities and that of his ancestors who had sailed this sea path a thousand years ago. He found land after 30 days at sea with an error of perhaps 30 miles.

The film was released in 1983 nationwide on the Public Broadcasting Service. It went on to be presented around the world on the BBC in Great Britain, Antenne 2 in France and many other television venues. Today it continues to be screened in theatres and schools and in open fields under palm trees. But more importantly, the skills that Mau passed down to his students continue to be practiced throughout the Pacific. He spent the remainder of his life, on his home island of Satawal, in Tahiti, Hawaii, New Zealand and many other places sailing and teaching — a never-ending work of deep passion to preserve a way of life that had been entrusted to him by his father, grandfather and a line of ancestors extending deep into the past.

On our last day of filming on Satawal, I asked Mau a question that seemed at first born from a kind of idle curiosity on my part. “Why did you work so hard with us over the last three weeks to help us make this film?”

His answer surprised me: “I wanted to make this film because when the young people see it, they will realize how important navigation is. Because when I die, I am afraid that navigation will die out here.”

His response placed our work with him in an entirely new perspective. I had come to Satawal to use Mau as a representation of the living past, to bring to life the kind of culture once widespread throughout the Pacific. I did not know that he was using us in a last-ditch effort to deploy modern media to overcome the forces of change that were then sweeping away his island’s ancient seafaring culture. At that time, in 1983, the young men of Satawal were leaving to attend school. When provided with compasses, GPS and charts, fewer and fewer were interested in learning the ancient ways. We were part of his plan to preserve knowledge that was sacred.

In 2007, I made my last voyage to Satawal to attend a ceremony called pwo. Mau had invited 12 students from his islands and five from Hawaii to initiate them as pwo navigators — fully trained to find their way anywhere in the world by merging themselves with nature. He had succeeded in his life’s mission.

Today, Hokule’a is on a voyage around the world on a mission to call attention to the pressing need to live sustainably within our planetary budget of natural resources. No less important, dozens of young men and women are training to find their way on voyages both across the ocean and in life, using Mau’s knowledge.

On July 12, 2010, Mau died on Satawal.

The Navigators — Pathfinders of the Pacific, will be shown at the Martha’s Vineyard Film center on Sunday, April 24, at 4 p.m., sponsored by Sail Martha’s Vineyard. Hokule’a, the replica of an ancient Polynesian canoe will visit Martha’s Vineyard at the end of June or early July. She plans to tie up at Tisbury Wharf, where the whaleship Morgan landed, courtesy of Mr. Ralph Packer. Sam Low is a former Hokule’a crewmember and the author of Hawaiki Rising – Hokule’a, Nainoa Thompson and the Hawaiian Renaissance. He lives in Oak Bluffs.

Comments

Comment policy »