When Arlene and her two young boys were evicted from their home in Milwaukee a few years ago, they found themselves in a cycle of poverty and eviction that affects millions across the country.

Their story is one of several in Matthew Desmond’s new book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, which illustrates how eviction is not only a condition but a cause of poverty.

“Housing is a fundamental human need,” said Mr. Desmond, an associate professor of sociology at Harvard and winner of a prestigious MacArthur “Genius” grant to help him explore poverty and eviction on a global scale. “Without a stable shelter, everything else falls apart.”

Mr. Desmond spoke to a crowd of around 100 people at the Chilmark Community Center on Sunday evening as part of the Martha’s Vineyard Author Series. He described his time living in poor neighborhoods in Milwaukee and getting to know families whose lives had been upended by evictions. The result was a new understanding of how poverty and evictions are linked in American cities, and how the country might move forward.

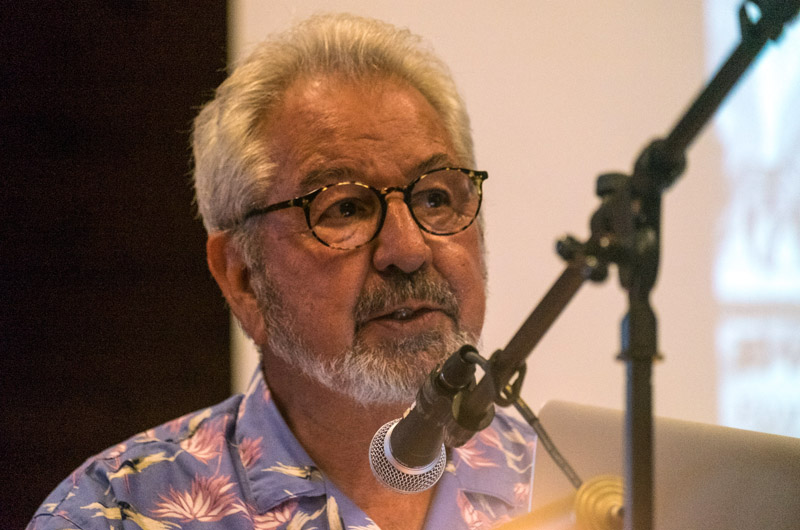

Longtime Islander Bob Vila, formerly the host of This Old House and Bob Vila’s Home Again, offered an introduction, recalling his own journey in the world of housing, and a growing awareness in the 1980s of the problem of homelessness in the United States.

“Here we are, 30 years later, looking at a situation that continues to be very aggravating,” Mr. Vila said, adding that Mr. Desmond’s new book “has been pivotal in changing the understanding of extreme poverty and economic exploitation.”

The story of Arlene’s eviction is both tragic and common. It begins when her son throws a snowball at a passing car, and the irate driver kicks in the door of her house. A short time later — just a few days before Christmas — the family is evicted. They bounce from place to place in the city, shut out by dozens of landlords based on their recent eviction.

“America is weird,” Mr. Desmond said, framing the problem. “There is no other advanced democracy that has the level of poverty that we do, and the kind of poverty that we do. And that’s always bugged me.”

When Arlene finally signed a new lease for a run-down duplex in a poor neighborhood, her $550 monthly rent amounted to 80 per cent of her welfare check, leaving no money for books and toys for her kids.

“Arlene is not alone,” Mr. Desmond said, citing data that rents have soared in the country while lower incomes have been flat or falling. One in four poor families spends 70 per cent of its income on rent and utilities, he said, compared to the 30 per cent widely acknowledged as affordable. Two-thirds of the poorest families who pay rent have no housing assistance, with people in some cities waiting decades to come up for review.

About 40 people are evicted every day in Milwaukee, a rate that Mr. Desmond said was commonplace in the poorest neighborhoods in American cities. Half of all evictions in Milwaukee were done out of court — highlighting the importance of on-the-ground work by Mr. Desmond and others to evaluate the problem.

African Americans, and mothers in particular, are evicted at a much higher rate.

“This is like the women’s version of incarceration,” Mr. Desmond said. “Many poor African American men are being locked up. Many poor African American women are being locked out.”

In many cases, evictions lead to more severe poverty, with consequences that keep the cycle going. Between seventh and eighth grade, for example, Arlene’s oldest son attended five different schools and struggled socially. One day he kicked his teacher in the shin. When word reached the landlord, the family was evicted again.

“[Kids] can prolong the time you are homeless after your eviction, and they sometimes are the reason for your eviction,” Mr. Desmond said. Looking back on the study, he added: “It wasn’t race, it wasn’t gender, it wasn’t how much you owed a landlord” that often got people evicted. “It was kids.”

He recalled how the relentless ordeal affected Arlene, who sometimes found her body trembling and said she felt like her soul was messed up. But he also noted her resilience, and her desire to see her kids succeed. “We’ll be remembering stuff like this and be laughing at it,” he said, quoting Arlene directly. He paused for a long moment while the room remained silent.

“The home is the center of life,” he continued. “In languages spoken all over the world, the word for home encompasses not just shelter, but warmth and family, safety, the womb. Eviction causes loss. Families not only lose their home, but often their school, their neighborhood, their possessions, furniture, clothes, books.”

He saw promise in the use of housing vouchers to help people maintain affordable rents, but also noted that the vast majority of people never get them. He also noted “huge strides” in addressing poverty in the United States in the last 100 years, but pointed to a long road ahead and the need for big solutions.

“We can’t go small on this issue,” he said. “We are bleeding out. We can’t settle for bandaid fixes.”

In closing, he outlined a broad initiative for addressing poverty and homelessness in the country through a universal voucher system. At about $22 billion, it was a pricy solution, he said, but one he felt was well within reach. He noted that tax benefits to homeowners in the United States exceeded $171 billion in 2008 — more than the budgets of several federal departments combined — with most of that money supporting people with six-figure salaries.

“Let’s just be honest about that,” he said, “and stop repeating this line that this rich, rich country can’t afford to do more. If poverty persists in America, it’s not for lack of resources. Maybe we lack something else.”

“This degree of inequality, this cold denial of basic needs, this blunting of human capacity, this isn’t us,” he said.

The Martha’s Vineyard Author Series continues Thursday with a conversation with author Richard Russo at the Chilmark Community Center. For tickets and information, visit mvbookfestival.com.

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »