Vineyarders were among the first whalemen to venture into the Alaskan Arctic, and among the last. Beginning in the 1840s, when the first Island ships crossed the Bering Strait, the unforgiving Arctic winters — along with the later advent of petroleum and steel manufacturing — ushered in the end of the whaling era in New England. But the names live on, both on the Island and afar.

For the first time next week, Alaskans and New Englanders alike will gather for a three-day conference centered around whaling in the Arctic, with events in New Bedford and Nantucket, as well as on the Vineyard. Stories of the Whale: From New England to the Alaskan Arctic will cover a wide range of topics, from history and heritage to current research surrounding whales.

Historian David Nordlander has spent the last two years organizing the conference, working with the International Fund for Animal Welfare, the Nantucket Historical Association, the University of Alaska, the Alaska Fisheries Center and other groups. The conference kicks off Monday with speakers and discussion at the Nantucket Whaling Museum, then heads to the Vineyard on Tuesday for a private tour of historic sites and a gathering with members of the Wampanoag Tribe in Aquinnah. It wraps up Wednesday with a series of roundtable discussions and scientific presentations at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Only the Nantucket and New Bedford portions are open to the public.

“Whaling is actually a major topic in the history of Alaska,” Mr. Nordlander said this week, noting the many native Alaskan villages that still depend on the sea. “Marine mammals are literally their subsistence and have been for eons. What’s interesting is those communities had a historic connection, beginning about the mid-19th century, with whaling ships from Nantucket, New Bedford, Martha’s Vineyard and other parts of New England.”

In the height of the whaling era in the mid-1800s, Vineyard whaleships plied the waters off Africa, South America, Japan and almost anywhere whales were known to swim. Their cargo and the resulting profits helped build Edgartown and Tisbury, where many captains and financiers remain immortalized in the names of historic houses and roads

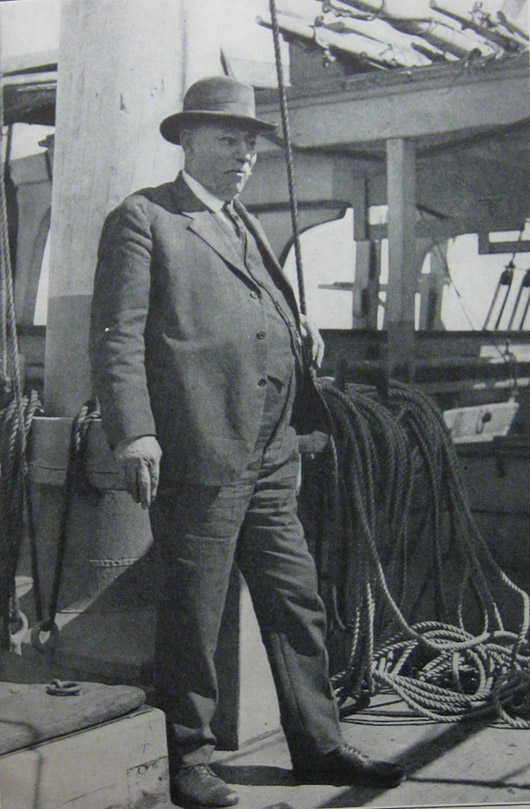

Hartson Bodfish of Tisbury, for example, was among the first whalers to overwinter in the Arctic, leading the way for many others. And like others, he also left behind a family.

An article in the Dukes County Intelligencer in 1971 lists 47 Vineyarders who whaled in the Arctic between 1848 and 1914. Many of their names are still common in New England today: Bodfish, Coffin, Cottle, Fisher, Jernegan, Pease, Tilton. Some of the names are also common in Alaska.

“The Inupiat people from that region have these names,” Mr. Nordlander said. “So they are interested to come here and actually see some of this legacy, which is really a family history for them.”

State Rep. Ben Nageak, a member of the Inupiat people, will take part in the conference, and hopes to learn more about his New England heritage.

The ships themselves often met their end during the long winters, stranded in the ice or shattered under the force of freezing and thawing. More than a few whalemen endured marches back to civilization over ice and snow.

Joseph Belain, a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, was known for rescuing the survivors of one crew during the brutal winter of 1897, building lightweight canvass boats and taking charge for Captain Whiteside of New Bedford, who had fallen ill.

But the Arctic ventures were the beginning of the end for New England, with a series of disasters gradually crippling the fleet. Perhaps most notable was in the Whaling Disaster of 1871, when 40 ships were stranded between Point Belcher and Icy Cape with 1,219 men, women and children aboard. The ship masters crowded into whaleboats and made the 70-mile voyage to the vessels at the edge of the ice field. The passengers were soon rescued, although only one ship ever returned home. Of the 32 ships that were lost outright, 14 hailed from the Vineyard.

“It caused an economic depression in Edgartown for quite a while after that,” Mr. Nordlander said. “It was so significant that it was hard to recover from it, although whaling was already starting its decline.”

Members of the Wampanoag Tribe are looking forward to sharing stories about their families and culture. Nearly everyone in Aquinnah has ties to the whaling industry. “I can’t think of any family that doesn’t,” said Aquinnah tribal elder Bettina Washington, whose great-grandfather John Belain along with his father, George, were both Vineyard whalers.

“I’m just looking forward to meeting these Alaska native people,” said tribal elder Linda Coombs, program director for the Aquinnah Cultural Center, who is also a Belain by descent. “I don’t know if anyone has really established that they are related to the Wampanoags in particular, but that is going to be a very interesting thing to determine.”

Mrs. Washington said most knowledge of tribal whaling ancestry is passed down orally, and it was unclear just how many tribal members were involved in the industry. But she noted that at a tribal family-day event this year, children were asked to list ancestors who went whaling, and the names numbered in the hundreds. Mr. Nordlander said one member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has listed 433 tribal members who sailed aboard whaleships, including some in the Arctic. “It’s a big topic,” he said. “I can’t say exactly how many people there are, but I think it’s extensive.”

The conference may eventually lead to some online educational materials, he added, although the immediate goal is simply to commemorate whaling history and heritage and highlight some of the present day issues, including ship strikes and entanglement, which threaten whales in both New England and the Arctic. The walking tour on Tuesday will include a temporary exhibit at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum featuring objects and documents related to the topic. Mr. Nordlander has been working with the museum to digitize its collection of whaling journals, which would be made available on the Digital Commonwealth website. He noted that the journal of Captain Jared Jernegan’s young daughter Laura in the 1860s has been a popular subject in Alaskan schools.

Mrs. Washington, for one, saw the conference as another opportunity for the tribe to expand its horizons. She noted a visit in June from the Hawaiian voyaging canoe Hokulea, a festival in August that celebrated the connections between the Vineyard and its sister islands, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and recent visits from Wampanoag members abroad who have roots in the whaling era.

“All these people, whaling connects us,” Mrs. Washington said. “It has just really been a banner year.”

Comments (9)

Comments

Comment policy »