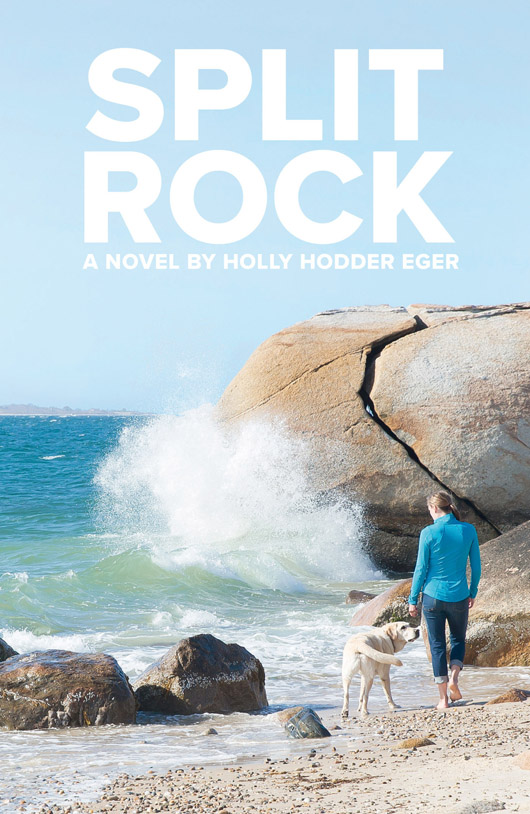

Holly Hodder Eger is not Annie Tucker. She’s been asked the question over and over, ever since her debut novel Split Rock was published this year. She is not Annie, but in creating the protagonist of Split Rock, Ms. Eger carved out a little piece of herself.

It started with grief. Ms. Eger’s aunt had died and she wanted to write about dealing with the grief, so she put it in a short story.

The short story eventually grew into a novel that would be published 19 years later.

Split Rock follows Annie, a stay-at-home mom of three children who moves with her family to the Vineyard for the summer after her beloved aunt dies. Annie deals with depression, temptation, uncertainty, fear and grief on an unconscious quest to find herself while rediscovering the magic of the Vineyard.

Sitting on Lambert’s Cove beach this week, looking out toward the landmark north shore boulder that inspired her book’s title, Ms. Eger recalled the many things that stood in the way of her finishing the book for so many years. She started writing it at 37, when her youngest child was still a baby. She was a stay-at-home mom and a corporate wife. Her family moved constantly for her husband’s job, between Kuala Lumpur, Rye, New York, San Francisco and Toronto, always carving out time to visit the Vineyard. Though she’d written for magazines, she hadn’t had a book published yet and was afraid to take time away from her children.

“You have to take yourself really seriously . . . . you haven’t had a book published and there are so many housewives, quote-unquote, saying they want to write books,” she said. “I had a girlfriend say oh, you’re just doing your writing thing, kind of like doing aerobics, or Zumba or something. That was hard, I had to just carve out the time on faith.”

Even when she wasn’t writing, Ms. Eger gathered inspiration that shaped the novel. Annie’s three children are unabashedly Ms. Eger’s children. Serious Robbie, trusting Lily and empathetic Meg are plucked from her own life.

“Those are my children at those ages, they just never were in those situations,” she said.

In truth, Ms. Eger constantly draws inspiration from the people around her. She was a frequent flier, and airplanes turned out to be an excellent source of ideas. But she always waits for her seatmate to begin the conversation.

“I love stories, I don’t talk, I just ask a lot of questions,” she said.

Fear was a driving force in the book’s journey. Ms. Eger stopped writing after her youngest child, in nursery school at the time, accidently dialed 911 while trying to call her grandmother. A policeman responded to the house, chiding her slightly. Terrified of neglecting her children for the book, her writing stalled.

“I was afraid to let myself get so consumed because I didn’t think I could do that and manage my children,” she said.

Fear again jump started the book. Her mother had just died of cancer, her father had Alzheimer’s and a scary call about a mammogram convinced Ms. Eger she was soon going to die. She thought immediately of her book.

“My first thought wasn’t about my children, because I had at that point felt I had poured every bit of myself into my kids, and now my youngest was 13 or 14 and I thought everyone is going to be okay, if I die everything is going to be all right — but I didn’t finish that book,” she said.

She began attending writing workshops at different colleges; then a Stanford University teacher suggested she stop talking about the book and just write it. So in the West Tisbury library and the cafes of San Francisco and Toronto, she donned her noise-cancelling headphones and transported herself to the summer of 1997, a time when the fairy tale of Princess Diana unraveled and email made its debut. She poured time into flawed characters, the book’s metaphorical split rocks. And when she got stuck, she would nap and dream about what happened next.

“I would never even know what my characters were going to say,” she said. “When I was really in the writing zone, I would go to the library and I would never really know what they were going to do that day. I had a rough outline.”

Once the book was finished, a year of revisions lay ahead along with the daunting task of finding a publisher. But after the protracted process of creating Split Rock, things started to move quickly for Ms. Eger. Her manuscript was discovered on her kitchen table by a Swiss woman whose husband happened to own a publishing company. The woman loved the book; her husband offered to publish it. On July 1 this year, Ms. Eger had 700 copies of her first novel in her living room in West Tisbury.

Though connections between Annie and Ms. Eger are impossible to ignore, the character, like most in the book, is a composite she said.

While Annie is accused of marrying on the rebound, Ms. Eger married her husband for another reason. They were dating when she was 24 and he won a fellowship to go to Malaysia. The only way she could tag along was if they were married. So they married.

“Little did I know that my whole next 25 years would be spent going back and forth to Asia,” Ms. Eger said. She studied English literature at Harvard University and then went on to get her master’s degree from the University of Virginia. Always a New England girl, Ms. Eger grew up in Belmont. She began visiting the Island in 1978 as a babysitter for a family on Middle Road. She would take the children to Lambert’s Cove to swim in the cool, clear water and play on the sand.

“The boys are now in their 40s and I haven’t missed a summer,” said Ms. Eger.

In 2000, she bought a house in West Tisbury.

Though a realist, she believes in Vineyard magic. Split Rock is full of magic, but it is the kind of everyday magic that crops up in life when you look for it. A cardinal that always seems to be nearby, a dog that acts more like a person, a town that always knows your business.

But as a woman at a recent book club meeting told Ms. Eger: “That’s the Vineyard.”

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »