As a young man Edward Hoagland once crawled into a cage with a mountain lion. But he wasn’t scared.

“She was in heat,” he said in a recent conversation with a group of students. “So I figured she wouldn’t attack a potential suitor.”

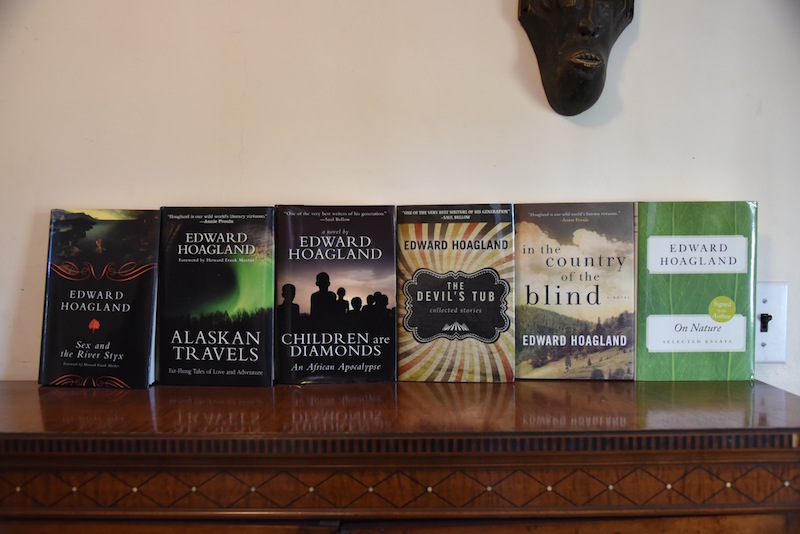

It’s that kind of immersive journalism that has made Mr. Hoagland one of the premier nature writers of the past several decades. He is the author of 25 books, most of them nonfiction. They range from roaming backyard streams to wandering the world, from Africa to Alaska and nearly everywhere in between.

For Mr. Hoagland’s newest book, out last month from Arcade Publishing, he has turned his attention to fiction, something he has done periodically throughout his career. In the Country of the Blind is his fifth book in six years, he is pleased to point out.

“Maybe not much for one in their prime,” he says with a smile. “But for an octogenarian it is unheard of.”

When referring to his age, Mr. Hoagland asks the phrase be “turning 84.”

“It’s much more active and interesting than writing he is 83, or he is 84,” he says. “You learn that from a lifetime of working with words. Active words help.”

Throughout his long career, Mr. Hoagland has written with joy and exasperation about the world he loves, a place he notes that man seems determined to destroy. His essays run toward the rueful, so many wild creatures and their habitats facing extinction, to downright upset over the lack of face-to-face communication brought on by the digital age. But no matter the subject, his vocabulary always sings, sounding high notes even when detailing our lowest selves. How else to explain feeling a sense of joy while reading about the end of the world as we know it?

In addition to traveling all over the world for his essays, Mr. Hoagland has lived for long periods in New York city and Vermont. These days he lives in Edgartown with his partner Trudy Carter, a therapist with Hospice of Martha’s Vineyard. He writes all day, every day, pecking away at two Olympia typewriters (one for his books, one for his journal), while classical music plays in the background. He doesn’t mind interruptions, he says, in fact he embraces them.

“Because I write all the time, I can easily return to my work,” he says.

While walking about the neighborhood near his Edgartown home, he wears a green felt fedora, much like he did when traipsing all over the world. But these days he also carries a cane, a white one signifying that he is blind. Mr. Hoagland first went blind about 25 years ago, due to cataracts, but an operation restored his sight. A few years ago, however, his sight began fading again, and now he can barely make out shapes directly in front of him. His blindness gives him unique insight into the main character of his novel, Press, a 46-year-old former stockbroker from Connecticut who has moved to a cabin in Vermont, nearly off the grid. The time period is the Viet Nam era, with a hippie commune just down the road from Press’s cabin.

Press is newly divorced and now living alone, estranged from his wife and two young children. Many, including his wife, see his blindness as a handicap akin to old age, and want him to live out the rest of his life in an institution. But on the mountain, surrounded by small town folks, Press finds compatriots willing to lend a hand, and not fleece him at the grocery store when he pays with too large a bill.

Blindness definitely doesn’t hold him back with the ladies, either. He meets a young mother, trying to make a go of it at the commune, and the two begin an affair. Another nameless woman also seeks him out because she wants a child but not a father. It seems Press’s lack of vision makes him a more acceptable representation of the patriarchy, one without the power to dominate or to even lay claim to a child.

Press’s blindness also gives Mr. Hoagland ample opportunity to set a scene through the other senses.

"Feeling the windchill, he gazed into the sky for a forecast, triangulating by the wind. He could hear rain and smell humidity. The big barn’s shape, the house, and shade trees were visible, along with the overgrown log truck track leading down into a cedar and tamarack forest bordering the swamp. For exercise he liked to descend and wend back up, careful not to stray onto a game trail or side path, where he’d get lost. The wood thrush calls around his house were a beacon."

In the Country of the Blind takes its time, most firmly anchored in the terra firma of the Vermont woods. There is an undercurrent of quiet desperation in Press’s predicament, but the surface feeling is, inexplicably, joy. His blindness could make him a target of others, and while that is true in some respect regarding his family, out in the world it feels as if his loss of sight has been offset by connection — with nature, of course, but even more so with people.

To visit with Mr. Hoagland in Edgartown — at his home, in the streets, in a pair of rocking chairs at the St. Andrew’s Church rectory (he likes to sit there in the sun, like a turtle on a rock) or while he teaches a class — is to understand why this is so. In the same class where Mr. Hoagland described to the students his near affair with a mountain lion, he responded to a question about where he gets his ideas and what to write about.

“You write about what you love,” he responded. “It’s as simple as that.”

Comments (7)

Comments

Comment policy »