Superior court clerk Joseph E. Sollitto Jr. is taking names. It is 9 a.m. on a rainy April morning, and 65 jurors are crowded into a basement room at the Edgartown courthouse. Joe, as he likes to be called, is walking the potential jurors through the first phases of the process, taking their juror cards, telling them where to sit, and in some cases, how to turn off their phones. He then announces that there has been a computer glitch and some people will be dismissed immediately. Everyone in the room looks up. The question, “Do I get to go?” hums in the minds of all in the room. Joe summons a few to the front of the room and releases them. A collective sigh goes around the room among the remaining potential jurors. They know they are here for at least the morning. Texts are tapped out to employers. Books and newspapers are picked up again.

Joe, who has been doing this for 41 years, ignores the discontent and launches into his speech for today’s jury pool. It’s a talk that he has clearly given hundreds of times. “Now, if you do get chosen, who knows? You might even learn something,” he says. Then he presses the play button on a VCR connected to an ancient television.

As he walks out of the room, clambering up the stairs to the second-floor courtroom, he shakes his head. “The TV is so old that it takes three machines to play the jury video on it.” He points to walls and ceilings, which have been crudely retrofitted with wiring and fire alarms. An old building trying to keep up with modern times.

Joe has been up since just after 4 a.m. He has done his morning sit ups and weights, taken the dog for a walk and had a bite to eat at home. He has been at his desk since a little after 6 a.m. He likes the quiet time at the courthouse before things get rolling at around 9 a.m.

April, along with October, is when the Dukes County superior court holds twice-a-year sessions. Today, a sensitive criminal case is on the docket, and Joe will assist as the Hon. Mitchell Kaplan and four lawyers impanel a jury. Even though 65 potential jurors have been called, he doesn’t think it will be enough to find 14 people who can hear the case. So he has lined up another 65 potential jurors to be vetted for tomorrow. In addition to scheduling all the criminal and civil cases for the superior court and processing jurors, his office is also the clearinghouse for processing passports and parking ticket appeals.

Joe hears parking ticket appeals in the early mornings. He says he’s heard all the excuses.

“I think my favorite excuse for a parking ticket was from a woman who called and said, ‘I’m 92 years old. I am too old to be getting parking tickets.’ ” He shakes his head and smiles. “I laughed and said I had to agree.”

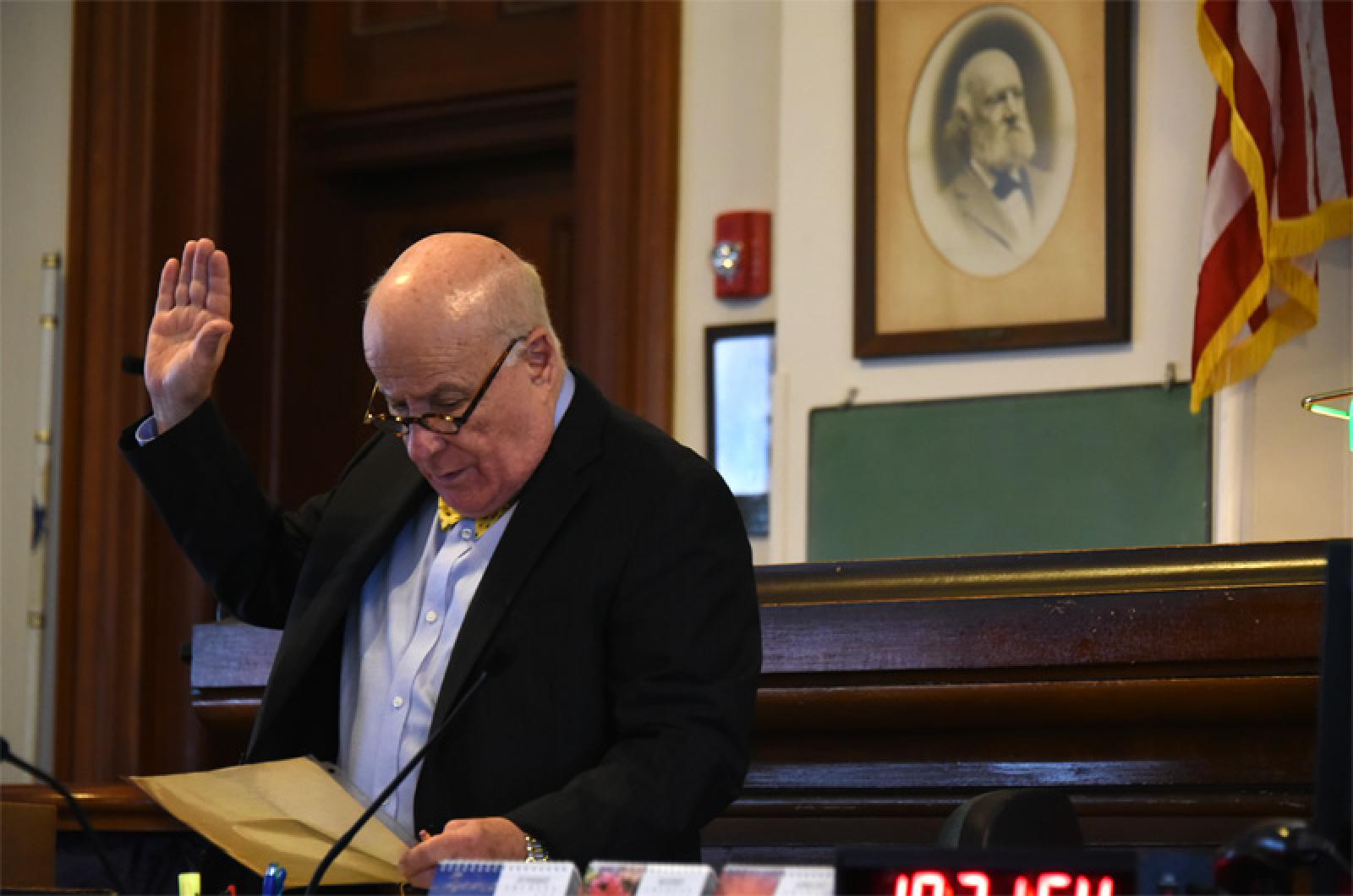

Judge Kaplan pokes his head into the office to say that he’s ready to begin. Joe jumps up and swaps his black Vineyard Ice Hockey vest for a sports jacket. Sporting a yellow bow tie, starched blue oxford-cloth shirt with his monogram over the left breast, crisp trousers and round tortoiseshell glasses, the clerk of courts could also pass for a professor on any college campus. He is quick to note that if he hadn’t pursued a career in the legal system, he would have been a history professor.

The statement bears true as he enters the courtroom and demonstrates an exhaustive history of the courthouse, judges, and cases. As he greets the defense and prosecuting attorneys, he points across the room to a picture of Sofia Campos, his predecessor who was clerk of courts for 57 years. “Mrs. Campos was like a second mother to me,” he says.

The judge enters. All rise. Joe occupies a desk just in front of the bench, where he jots notes on a yellow legal pad and mans the recording of the session. He says he misses the court stenographers. “They used to help us with the exhibits. Or if I had to leave the room to do something, I could. Now I cannot leave until the judge leaves.” A court officer brings in the potential jurors. The judge speaks to the crowd, asking a few general questions. The process of voir dire — interviewing each potential juror — begins. Two and a half hours later they have gone through the entire group of 65, and have selected just five jurors for the case. As predicted, they will have to pick up again tomorrow when another 65 jurors will be called. The afternoon will be dedicated to pretrial motions, but first there is a break for lunch.

Joe packs up his court desk, which still has old-fashioned rubber stamps lined up. As if anticipating the question of how he handles the day in and day out of living with crime, upset and hurt, he pulls out a black binder that holds all the mandatory texts for a clerk of court’s job. He points to a page quoting G.K. Chesterton’s “The Prisoner in the Dock”. It reads:

The horrific thing about all legal officials, even the best, about all judges, magistrates, barristers, detectives, and policemen, is not that they are wicked (some of them are good), not that they are stupid (some of them are quite intelligent), it is simply that they have gotten used to it.

They simply do not see the prisoner in the dock; all they see is the usual man in the usual place.

They do not see the awful court of judgment; they see only their own workshop.

As he walks out of the courtroom, he adds a thought. “My wife says I compartmentalize. All I know is that I don’t bring this home with me. My work and all that I see and hear stays here.”

Joseph Edward Sollitto Jr. came to Martha’s Vineyard in 1968 to drive a tour bus, a summer job to pay for law school. On his second day on the Island, he decided that it was his place. Because he had served in the Marine Corps, he was soon hired by the Oak Bluffs police department. When he returned to school in the fall, he would come down to the Island on the weekends and stay at Jimmy Marshall’s house, working police duty, taking night shifts. “It was pretty quiet in the fall and winter months. There wasn’t much to do,” he recalled. “Only the Ritz and the P.A. club were open so I would do door checks on Circuit avenue and then I could study. Every once in awhile someone would call needing an ambulance. Those were the days when one person operated an ambulance, so I’d have to go or find someone to go to help carry the other end of the stretcher.”

When he graduated from Suffolk University Law School and passed the bar, he got a job at Hill & Barlow of Edgartown (now Worth & Norton), working for Jeff Norton. The work was mostly real estate transactions and he didn’t like having to keep track of the time so that he could bill the right person. At the time, Mrs. Campos, as he still calls her, needed help at the courthouse. Joe filled in. He liked the work. In 1974, Mrs. Campos hired him to be her assistant clerk of the courts for the county of Dukes County. In 1977, after she retired, he ran for office and won the seat. He jokes, “I am the only Republican some people have ever voted for in their life.” Then turning serious, he says: “With this job, I saw the potential for doing a lot of good. We all make mistakes. I see and know how the law can and does help people.”

Joe’s civic work has included holding public office — among other things, he was an Oak Bluffs selectman from 1974 to 1977. He also helps lead the Edgartown Fourth of July parade, and proudly took over when longtime parade marshal Ted Morgan retired recently.

He heads back to his office, checking in with his two assistants, Paula Berube-Delaney and Susan Pience, who sit in an anteroom.

His office is a mishmash of memorabilia — degrees, clocks, magnets, an old phone, a campaign pamphlet from his run for office in 2006, radios, books, post-it notes, photos, paintings — and boxes and boxes of legal files. His giant wooden desk, which he refinished and schlepped up the narrow courthouse stairs with his good friend Richie Giordano, takes up half the room. The courthouse’s giant safe sits behind him, holding documents from its earliest days. A photo of Island attorney Robyn Nash sits on his desk among the requisite family photos of his wife Kathy and stepdaughters Kara and Elizabeth. “Robyn Nash is a hot ticket. I swore her in as a lawyer,” he says. “She invited so many people to the event, we had to do it in the jury room downstairs.”

He laughs at the memory and continues: “She has been suffering from cancer. Fighting it for 10 years or so. My last and final run to be clerk of courts was my only contested race. So I had to campaign. I made all kinds of pamphlets, a nail file that says, “File Your Vote with Joe Sollitto,” and on election day, I was out on the street holding up a sign. And I hear this car pull up next to me. I see that it is a station wagon and out rolls Robyn, no hair from the chemo, draped in a blanket. She pulls a chair out of the car and sits down next to me.” He pauses, his voice catching. “And she sat with me, in the cold for an hour. She is a very special person.”

He has had his own battle with cancer. He is now in the clear and grateful. He mentions dozens of other special people with whom he has worked with over the years. The people who mentored him. The lawyers he holds in the highest esteem. He pulls out photos or old notes to illustrate points. It becomes clear that while he may compartmentalize, he remains profoundly affected by his work and all the people he comes into contact with. He shares some more on his favorite subject: Edgartown courthouse history. This somehow leads him to talk about his two stepdaughters, and he beams with pride over them. This leads to the story of his marriage, and his parents dying within a day of each other after 61 years of marriage.

Then the phone rings and Joe goes back to work.

Joseph Edward Sollitto Jr.

Age: 73

Born and raised: Roslindale, West Roxbury

Moved to Martha’s Vineyard: 1968

Profession: Clerk of the Courts, Superior Court Magistrate

Education: Stonehill College, Suffolk University Law School

Served: United States Marine Corps 1965-1967

Wife: Kathleen D. Sollitto

Children: Two stepdaughters, Elizabeth R. Taylor and Kara L. Taylor

Pets: Sophie, an eight-year-old King Charles Cavalier spaniel; Guido, a seven-year-old Maine Coon cat. (“I’m the cat person.”)

Avid fan: The Boston Red Sox. He has a dedicated radio in his office for following games.

Signature retro accessories: A bow tie and a flip phone.

Cool cars: Owns a 1926 Model T and a 1933 Ford

Comments (15)

Comments

Comment policy »