From the May 9, 1947 edition of the Vineyard Gazette:

The pugs bite, and spring is here; not because the pugs are abroad, but because they will take a hook. And neither is it spring because they will take a hook anywhere, but because they will take in the open water. All of which is something odd, but the pug, well, the pug is something in the fish line that is a law unto himself, and let’s see anyone capsize the natural program of the critter.

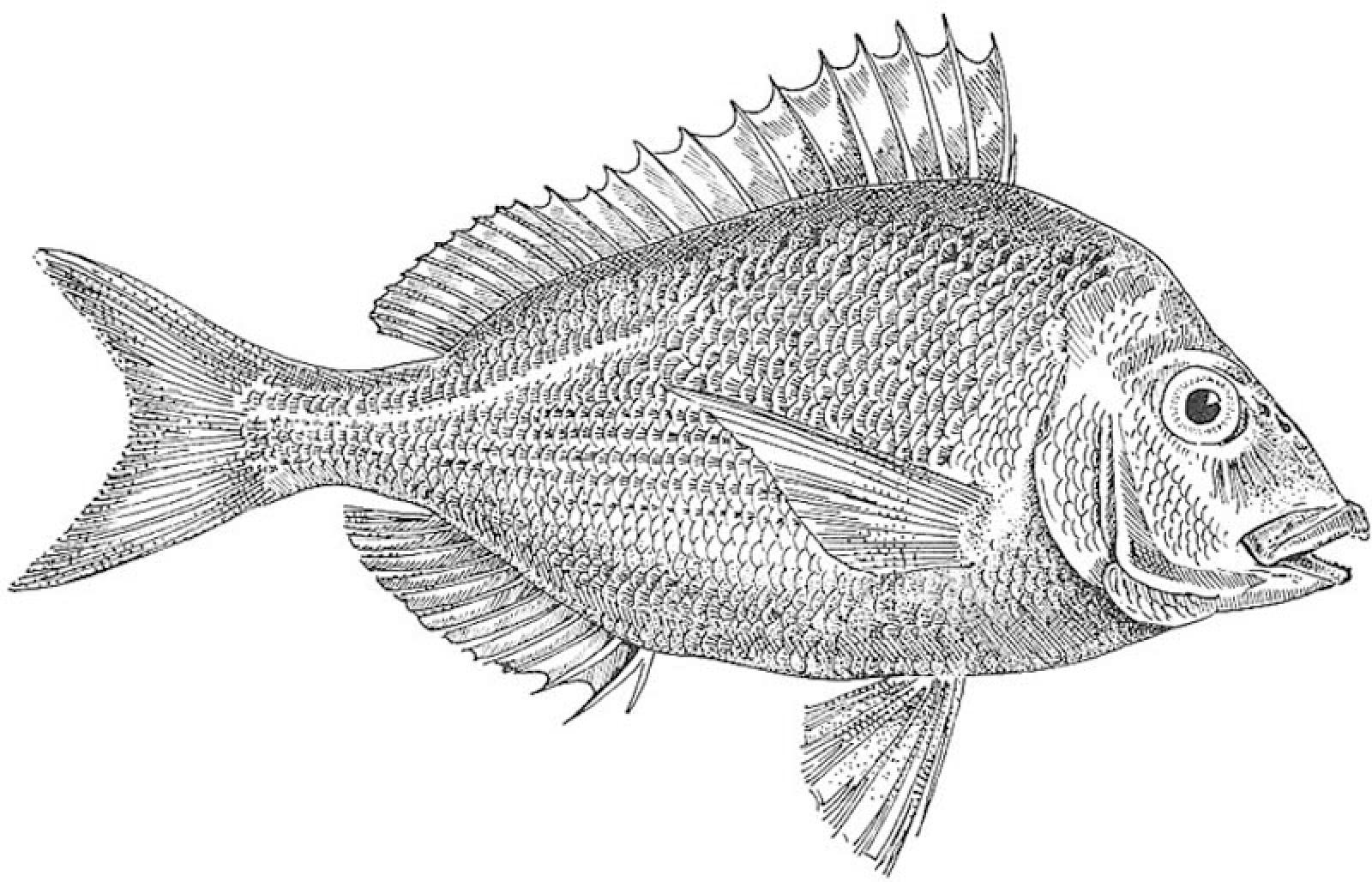

What is a pug anyhow? Plenty of people, mostly pilgrims, ask this question, and it has been answered again and again and again, as somebody used to say. Local belief is that the native Indian attached the name of “paug” to various kinds of fish, in conjunction with a descriptive syllable, such as “scaupaug,” generally known as “scup” today in this locality.

Then there is another theory that the nose and mouth of this fish somehow resemble those of the pug-dog of the Gay Nineties. Perhaps it does, on a very miniature scale, but right or wrong, it is a pug so far as the local fishermen and ultimate consumers are concerned.

Getting away from the local people and the pug masquerades under various names, depending upon where he is found, and how large he may be. For the sole, the winter flounder, and on occasion, plaice, may well have started out in life as the ordinary pond pug, as the oldest of Islanders used to call it.

There are undoubtedly places in the sea where the pug habitually spawns. No doubt the same authorities who have followed the eel to the Bahama Bank and back, know exactly where this is. Local people have never given it much thought, but from the presence of pugs no more than an inch long in the salt ponds of the Vineyard, it has always been believed that these places are more or less favored by the “inshore run” of these fish. That others go elsewhere is generally accepted by fishermen.

In older days, when cold storage was not known and very few vessels pursued the fish in winter, Vineyarders seined the great ponds, and along with the perch which they sought, they captured numbers of these sole. At such times they were usually small, perhaps no more than six inches long after the heads had been removed, and even smaller at times, but they were fresh fish and, browned in the pan, brought delight to the “fish hungry” people of the Island towns.

But it was not possible to seine at all times, and the movement of these fish was closely watched. As soon as they would take a hook, a time which depends upon the weather, there were people looking for them. It is even so today, for the fisherman who goes for sport is as unchanging as the passage of time and will ignore no opportunity, however slim, to dip a line into water, be the atmosphere what it may. And it is not to be supposed that a single specimen of the spring flat fish even goes to waste; there is always someone who is eager to dine off his sweet, juicy flesh.

But the pug, flatfish, winter flounder or what-have-you, is a creature of moods, or deeply-centered habits. This year, 1947, the first pugs to be taken in open water with a hook were landed April 26, which is admittedly early.

Yet they had been seen, sculling around in shoal water, weeks before that, and had been taken with a hook in salt ponds more than a month before. Oh yes, agree the oldest inhabitants, they always bite earlier in the ponds than outside. Why? Well, that again is a query for the scientists; the local people do not know and refuse even to guess, but it is so.

And then there is the question of bait, which may or may not have much to do with it. One group will swear that nothing is as good as the wriggly, leggy clam-worm either brown or red. It’ll catch ‘em, there is no question about it. Another will reveal, with glowing pride, the store of scallop-rims, salted last fall, and preserved with care for this purpose. It’ll take ‘em, too, and no one disagrees about that. But there are others who have good luck with a quahaug, freshly dug, and others still who regard as best of all the razor-clam, carefully sliced - and all have luck.

But the habitual clam-digger who wades on the winter flats and delves for his prey in the sand and mud, will tell you that even in mid-winter, when the water is iced over, and the temperature is down to freezing, he has had pugs swim right to him, following the cloud of bottom mud which has drifted to looward from his rake. And he will be telling the truth.

All of which is relatively unimportant. What does matter is that as of this date the pugs are biting and the boats are out, whenever it’s warm enough to keep from freezing and calm enough to keep from sinking. And the pugs are as welcome as ever, despite the stores and markets filled with fresh fish. For the Vineyard retains many of its ancient instincts, and will go down to the sea according to what the calendar may state, there to play the sport that was a necessary and comfortless task in grandfather’s day.

Compiled by Hilary Wall

library@mvgazette.com

Comments

Comment policy »