Erica Armstrong Dunbar was at work on her doctoral dissertation on the lives of black women in the antebellum north when she came across a newspaper advertisement that caught her attention.

The advertisement, dated May 24, 1796, described a runaway slave named Ona (“Oney”) Judge, and offered a $10 reward to anyone who could return her to her household. The slave owner was President George Washington.

“There was something that told me, you know, this is a separate project, and I don’t want to short shrift her...so I will come back to the story of Ona Judge, to try to figure out what became of her,” Ms. Dunbar said.

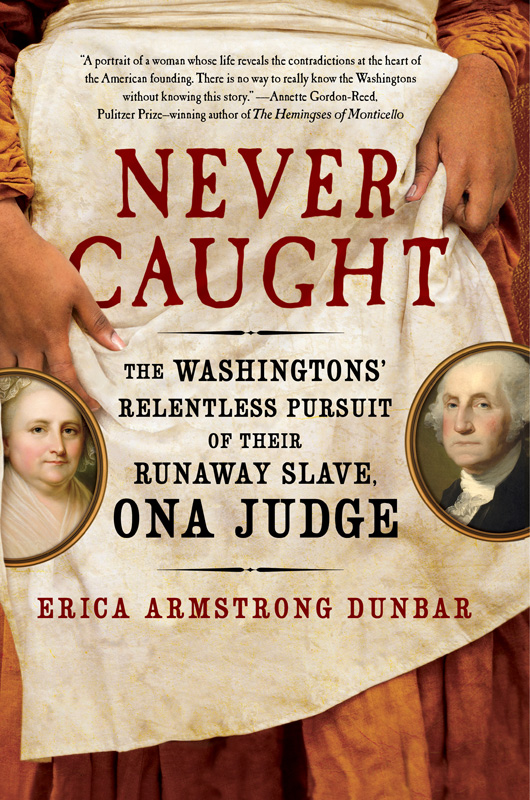

With the publication of Never Caught, roughly 20 years later, Ms. Dunbar has done just that. She called the account, “A corrective to the kind of history that we’re accustomed to.”

“It became a book that allowed us to look at the founding of America through the eyes of the enslaved. And so of course Ona Judge is centered in this narrative. But the project became larger... it was also to have us think deeply about presidential history, it was also to have us think deeply about the ending of slavery in the north and its perpetuation in the south.”

The book begins in 1773 with the birth of Ona Judge, who was born to Betty, one of Martha Washington’s favored slaves. Ona grows up as George Washington assumes the presidency. Never Caught tracks these two intersecting paths.

After Mr. Washington’s election in 1789, the family moves, with Ona, from Mt. Vernon to New York, the first capital of the new republic. There Ona learns about the stirrings of black freedom in the North. The Washingtons then move to Philadelphia when it becomes the site of the nation’s capital.

In Philadelphia, President Washington grapples with his role as a slave owner, not least because of a Pennsylvania law which mandated the emancipation of adult slaves who lived in the state for over six months. Mr. Washington, however, with vested financial interests in the continuation of the practice, fashions himself as a benevolent slave owner, and goes to great lengths to circumvent the law, shuttling his slaves back to Mt. Vernon every six months to reset the clock.

In Philadelphia, a city at the forefront of the abolition effort, Ona is further exposed to the presence of free black people. It is in this milieu in the spring of 1796 that she makes her escape, spurred on by the knowledge that she would soon be given to Mrs. Washington’s capricious granddaughter, Eliza Parke Custis, as a wedding gift.

She sails to New Hampshire and takes up life as a domestic, but is pursued by the Washington family. Ms. Dunbar provides a suspenseful retelling of Ona’s close calls throughout the no-holds-barred effort of the Washingtons. They even enlist the federal government to get her back.

“Why pursue her when there were over 300 enslaved people at Mt. Vernon?” Ms. Dunbar asked. The answer isn’t clear. Ms. Dunbar suggested a few possible explanations, including the Washingtons’ sense of anger and offense that a slave would run off.

She added: “Ona lived in that house with them for many years. And for someone who was interested in protecting his legacy and protecting his image, she knew a lot. In some ways she could have been seen as a loose end.”

She also wondered whether a sexual relationship existed between the president and his fugitive slave, but said she couldn’t find any evidence to suggest as much. Ms. Dunbar drew on Mr. Washington’s correspondence, among a rich assortment of other primary sources, to piece together the riveting narrative.

The project, she said, took nine years of research. When she first encountered the advertisement that sparked her interest in graduate school, she was surprised at the dearth of scholarship on Ona Judge. Working on Never Caught, however, she learned why this was the case: “In terms of evidence that was available to tell the story, it was scattered and it was thin.”

Ms. Dunbar fills in the gaps with her expertise as a historian specializing in the lives of African American women in the early republic.

She explained: “If we only go by what is written in letters or diaries or documents, we are always going to be left out of the narrative, because so many people of African descent were forbidden from learning to read or write, and women in general often did not have access to education.”

“We have to think broadly and read between the lines,” she continued.

And while the primary source documentation relating to Ona Judge is sparse, she is the only fugitive slave of the Washington’s who left behind any testimony at all. Toward the end of her life, she gave interviews with two abolitionist newspapers.

“People need to understand their nation’s history,” Ms. Dunbar said. “And it’s my job to offer a different perspective, and that’s what I tried to do with Never Caught.” She added that the book provides a window into the lingering vestiges of slavery and gender and racial inequality in the country. It is also timely, she suggested.

“I think this book has us think seriously about presidential power, and I would argue that this is probably a really good time to read about that.”

Erica Armstrong Dunbar will speak on Saturday at 10 a.m. at the Harbor View Hotel, and on Sunday at 2:45 p.m. at the Chilmark Community Center.

Comments

Comment policy »