Carol Brown Goldberg’s parents expected her to look presentable, play with nice friends, get married and have children. She did all of those things. She also became an artist, painting intricate works of science and nature, windows into imagined cosmos, explosions of symbols and letters, and wobbly story book scenes.

“I got into art to move my hand,” she said. And movement has never been more apparent than in her most recent collection, Tangled Nature. Honoring Japanese woodcuts and Chinese artwork, “the concept of space becomes an object,” she said. Borrowing from the surrealists, she practices automatic drawing, letting the hand travel where it will, pen attached to the end of it. The image builds out on large canvases in intricate pieces. Lines connect to lines, lumps to lumps, and foliage is drawn the way it has been since she first put pen to paper, in an explosion of octopus arms.

At her home atop Peaked Hill in Chilmark on a recent morning, Mrs. Goldberg, a recipient of the Maryland State Arts Award, sat in her small studio, which she calls a crib. Behind her, tangled paintings grew and through the window the view tumbled over treetops and out to the blue ocean beyond. Splitting time between Washington, D.C., and Chilmark, Mrs. Goldberg has shown in over 100 solo and group exhibitions, and her work is included in museums and private collections across the country.

She grew up in Baltimore, Md. where, “no one escapes being quirky.” Her concept of the world outside her small Jewish community was confined to paintings from China and Japan that hung in her house. She attended a Jewish sleep-away summer camp in the Pocono mountains.

“It was a defining time, I went there for 13 years, my brothers went there, captain of the blue team,” she remembered. “It made me feel like I could do anything.”

She attended college and studied English, history and American studies, planning to write. But instead she got married and had her first child at 22. She had gone from her parents’ house to a sorority house to a house with her husband.

“I still think this is why I’m such a late bloomer and never grew up,” she said. “I was still sort of outgrowing my parents, and then when kids were born, I was back on the floor, thinking of my own childhood again,” she said. “I never really had a distance from my childhood.”

Her first piece of art was for her first child. During pregnancy, she flipped through children’s books from the library, picking out illustrations and then painted them into a mural on the wall of the nursery.

“I had never painted before and never copied from a book,” she said. It being the sixties, in the Maryland suburbs (Chevy Chase), she decided to take some private art lessons. Then in 1970, when her children were in school full time, she enrolled in the Corcoran School of Arts and Design. The head of the painting department asked her what her goals were.

“I was thinking, my goals are, let’s see, I have to pick John up at two and Bennett’s got a play date,” she said. But then he asked her if she wanted to show in a museum.

“I said, whoa, yes,” she remembered. At the time she went through art school, minimalism was the movement of the moment. But Mrs. Goldberg was never a minimalist. “I fill up space, more is better than less, I feel,” she said. “I do feel like I’m a Baroque painter, excessive.”

In the late 1970s a few crises entered her life, cementing her determination to become a serious artist. There were family changes, one of her sons needed surgery. At the time she was in her 30s.

“Insecurity is a partner with everything I do, it’s a way to keep me humble and scared,” she said. “I like all of that, I like being scared.” She took stock of the things she hadn’t done: she never took drugs, she never dropped out, she never lived in a commune. She asked her friends about the experience of taking drugs, and felt she’d experienced the feelings without the pharmaceuticals.

“A lot of my thinking was to try to compensate for how I didn’t live,” she said.

Her pieces began as Matisse-inspired paintings of wobbling village roads and piano rooms. It felt close to her childhood, to folktales and comic books. It felt like a memory. Then she became enthralled with science, physics in particular. She would read physics books, listen to books on tape while she worked and attend scientific lectures.

“I was using physics the same way surrealist used psychoanalysis and dreams and the subconscious,” she said. This translated into paintings that used “the alphabet as geometry,” exploding out from the center of the canvas in color and confusion. From the letters and symbols, she scaled back to focus on color. “I looked at the work, and I said, Carol, just focus on what you love, you

love science, you love color let’s go into the science of color,” she said, crediting Thomas Downing with inspiration.

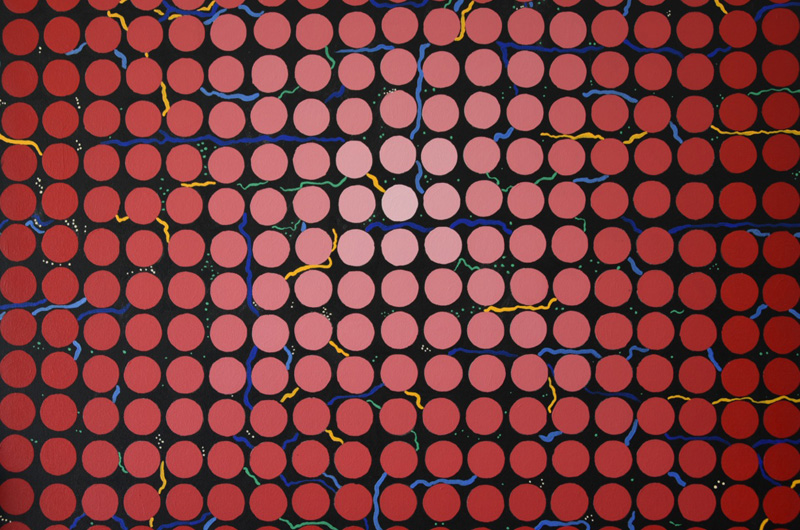

She explored gradients and light through circle paintings. Starting with the darkest pigment, she created a frame of circles around the edge of the canvas. Moving toward the center, each row grew a shade lighter, ending in the center with the lightest shade, a slightly-tinged white. The effect is yet another explosion, one of light emanating from the middle outward. Some of the circle paintings leave a window to the background of the canvas, a solid color perhaps, speckled with flicked paint and occasionally, glitter.

Mrs. Goldberg said she believes that an artist must evolve, not keep the same handwriting.

“To always think and be up to date with yourself in a way,” she said. “Your style is going to move and change and morph into something else.”

Along with her paintings and drawings, she creates sculptures and videos.

All of her work begins as a doodle, she said, before she begins to take it seriously. Her latest sample of handwriting shows an obsession with detail, with the natural world and its jumbled complexities. It shows an artist who trusts her hand to make the connections, the leaps and bridges between one side of the canvas and the other with an acrylic pen.

“I’ve always done a kind of landscape art, I would call it a mindscape, or a sciencescape, landscape, cosmosscape, universescape,” she said.

In 2016, she used no color in her paintings.

“During the election, there was so much noise and so much anxiety which to me took the form of color, that I felt like I didn’t need any color in my work,” she said. “So for a year I just did black on white canvas.”

The day after the November election, she painted a canvas angry red and choked it with reaching vines and knotted foliage. The painting is titled The Day After. Then she did a matching blue canvas with a little more light and a little more air, called Passive Resistance.

Any painting, any stroke of a pen or brush on the painting, captures one exact moment in Mrs. Goldberg’s life.

“It feels like I am marking time, each one of these is a nanosecond of being alive,” she said. “And maybe art making has always been a way of marking I was here.”

Comments (14)

Comments

Comment policy »