White shark research is booming from coast to coast, along with a growing population of white sharks. And the sharks themselves are passively aiding in the research, from great whites in the Pacific sporting “Shark FitBits” of sorts, to the sharks that will be traced by scientists when they swim by a new acoustic receiver just off Martha’s Vineyard.

With this information, scientists hope to find answers to some basic questions. “We’re very much interested in what these sharks are doing over multiple scales, time and space,” said Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries scientist Greg Skomal. “Where do they go, where do they spend their time, what’s their behavior?”

On Monday this week, Mr. Skomal had the kind of shark encounter that is helping to advance a growing body of research. Suspended off a boat and using a dart, the scientist implanted two different tracking devices in a white shark off Monomoy, the seventh shark Mr. Skomal and his team have tagged this summer. But the highlight of the day was underwater footage from a GoPro camera of a 12-foot female shark that gave the camera a curious bite, providing a close-up view of rows of sharp teeth and the wrinkly white world inside a shark mouth.

“We’ve never had that happen before,” Mr. Skomal said later.

Four days earlier and some 3,000 miles away, Chris Lowe, a marine biology professor and director of the Shark Lab at California State University Long Beach, tagged a baby white shark in the Pacific Ocean off Ventura, Calif. Mr. Lowe and his team surgically implanted a long-term acoustic transmitter in her 58-inch body and attached a satellite tag before letting her swim off in the sea, where scientists can track her for years as she grows up.

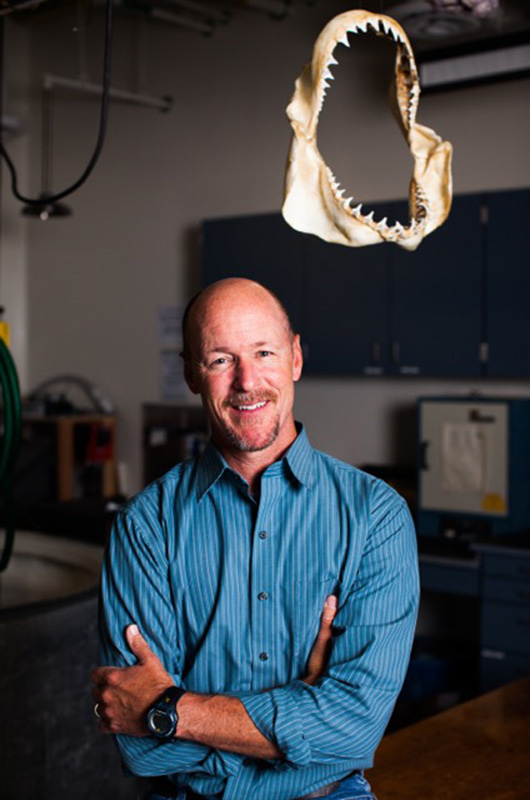

Sharks loom large in the public psyche during the summer, as beaches fill with swimmers, Island movie theatres offer weekly showings of Jaws, and an entire week of television programming is devoted to the ocean’s apex predators. For Mr. Skomal and Mr. Lowe, two preeminent shark biologists united by their area of research and long connections to Martha’s Vineyard, it’s the height of their research season.

There are at least a dozen sharks that come seasonally to Cape and Island waters. They include the small coastal sharks, like spiny dogfish and sandbar sharks, that are often caught off East Beach and Wasque. Further offshore swim blue sharks, makos, and thresher sharks. Hammerheads are seen from time to time here, Mr. Skomal said — one was reportedly seen off South Beach last summer. Basking sharks are seen offshore and inshore, particularly in June in the waters off Menemsha and Gay Head.

This diverse assortment of sharks congregates seasonally in Massachusetts waters, and scientists are researching several of these species. But looming over them all, on the food chain and in public interest, is the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. They are the largest predatory fish in the sea, skilled hunters equipped with speed, sharp teeth and keen abilities to smell and sense electric currents in the water.

In the latter part of the 20th century, when Mr. Lowe was growing up on the Vineyard, white sharks were rare.

“I fished all over that Island,” he said. “I never saw a great white shark growing up . . . now I hear they are everywhere. For me to see that and hear about that in my lifetime is actually amazing.” Mr. Lowe, the son of Lee and Snookie Tilton Lowe, descends from a long line of Vineyard fishermen. Fishing on the Island sparked his interest in marine biology.

“I remember catching dogfish as a kid, thinking that is just the coolest animal ever,” he said.

After studying in California and Hawaii, Mr. Lowe ended up at the Shark Lab at CSU Long Beach, a pioneering shark telemetry lab. In his earlier days, Mr. Lowe learned to build acoustic transmitters to track fish, a technology that has carried over to tracking a wide variety of species.

Mr. Lowe and others also use newer technology, including underwater robots and drones to take “shark selfies” and identify individual sharks. Tags still play a key role. The acoustic transmitter implanted last week in the baby shark off Ventura will help scientists track her for the next 10 years. The satellite tag she sports will track her depth and the water temperature for the next five months before detaching and floating to the surface. Scientists will then download data gathered.

Mr. Lowe and his team at Long Beach were the first in the world to show that the white shark population is increasing, an idea that drew skepticism when it was suggested in 2012, but is now widely accepted, he said. The Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972 protected shark prey, like seals, and state and federal protection of white sharks followed. Mr. Lowe pointed out that in many ways, the white sharks are a success story. “With that said, we’re not out of the woods,” he added.

Research in California applies to sharks in his home waters and beyond, though there are differences. A massive continental shelf off the East Coast is basically one big shark nursery habitat, he said. The continental shelf off Southern California isn’t as wide, which pushes the shark pups closer to shore. “The cool thing is I can go off Long Beach, in my very front yard, and catch and tag newborn baby white sharks,” he said.

Mr. Lowe’s research showed that the baby sharks are temperature sensitive, preferring water between 60 and 82 degrees. That makes Southern California an ideal habitat, he said. This research indicated that white sharks born off the coast of New York and New England during the summer would likely move south as the water got cooler, which the baby sharks did.

“I think as we learn more, we’ll start to see more of these similarities,” Mr. Lowe said, “but we’ll also see some of the differences that are attributed to each coast.”

Closer to home, scientists ply Cape Cod waters to study what seems to be a thriving white shark population. Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are looking at everything from shark migration to how deep they dive, including using the REMUS SharkCam. And the organization Ocearch has made several well-publicized shark tagging expeditions in the area.

Mr. Skomal, a noted shark biologist and the go-to shark guy in the area, is leading a multi-year shark population study for the Division of Marine Fisheries, with funding support from Atlantic White Shark Conservancy.

He will be the keynote speaker at an event sponsored by the conservancy on Tuesday at the Old Whaling Church in Edgartown.

From mid-June through October Mr. Skomal travels Cape waters looking for, identifying, and tagging white sharks. White sharks show up around the Cape during the summer season, apparently lured by an abundance of food, from the gray seals that hang out in large numbers on barrier beaches to schools of fish swimming farther offshore.

When scientists find a shark, and the boat can get close enough, they use an intramuscular dart to implant tags at the base of the dorsal fin.

Mr. Skomal has tagged 110 different sharks in the area since 2009, a number that is rising as the summer goes on. The sharks are identified by their markings and given names, like Pumpkin, Scratchy and Big Papi. This week scientists were flipping through the catalog to see if they can identify the female that nibbled on the GoPro camera.

Mr. Skomal doesn’t play favorites with his subjects. “Each one is interesting to me,” he said. “No two sharks act alike.”

The tags let the scientists see where the sharks go, as well as other vital information about their habits and ocean conditions. Acoustic receivers are deployed in the water around the Cape, including a new receiver deployed this summer in Nantucket Sound, just east of the Vineyard. The receiver will record the presence of any sharks with transmitters that come within 100 yards. Data from the receiver will be retrieved at the end of the season, and show whether sharks are indeed among the Vineyard’s seasonal visitors.

“I believe they pass south of the Vineyard. I’m curious,” Mr. Skomal said. “That’s a good first step.”

The receiver will also tell scientists how sharks are interacting with seals. “The more you know about the prey you the more you know about the predators,” Mr. Skomal said, and areas where sharks congregate around the Cape tend to coincide with popular seal habitat. In May a young gray seal called Miley Sealrus was released into the water after rehabilitation at the National Marine Life Center in Bourne. Miley swam off sporting satellite and acoustic tags that will let scientists track her movements. If a shark should eat the seal, scientists will be able to detect that, too.

This work comes along with intense public interest — both Mr. Lowe and Mr. Skomal were featured in Shark Week shows this year, and spent a lot of that week talking with the media. They also spend time raising funds for research — Mr. Lowe noted that though sharks are popular, that doesn’t always translate to funding — and addressing the fear surrounding sharks. Scientists note there hasn’t been a fatal shark attack in Massachusetts in decades.

Mr. Skomal said he would welcome bringing Vineyard towns, particularly those with south-facing beaches, into a group of Cape communities that discuss shark safety protocols.

“Not to say that there’s going to be a shark attack or anything like that,” he said. “But just to be proactive in terms of educating the public and putting protocols in place.”

While research will benefit scientists in understanding sharks, Mr. Lowe said, it also helps coastal communities learn how to share their environment with sharks.

“I’ve been arguing that we’ve basically had two generations of Americans that have had basically unfettered access to the ocean. We haven’t had to worry about predators because we eliminated them,” he said. “Now we’re seeing the recovery of those predator populations . . . but we are guests in their home, and we’ve got to learn to be better guests.

“And part of that is we need to learn more about these animals . . . what their needs are, how to avoid negative interactions. And that’s where the science becomes so important.”

Greg Skomal speaks Tuesday, August 8 from 7 to 8:30 p.m. at the Old Whaling Church in Edgartown. A suggested donation of $20 per person will benefit Atlantic White Shark Conservancy. Children 12 and under will be admitted for free.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »