Greg Skomal, former lead scientist of the Massachusetts Fisheries’ Martha’s Vineyard station, has detected, inspected, dissected and protected just about every species of shark in the North Atlantic.

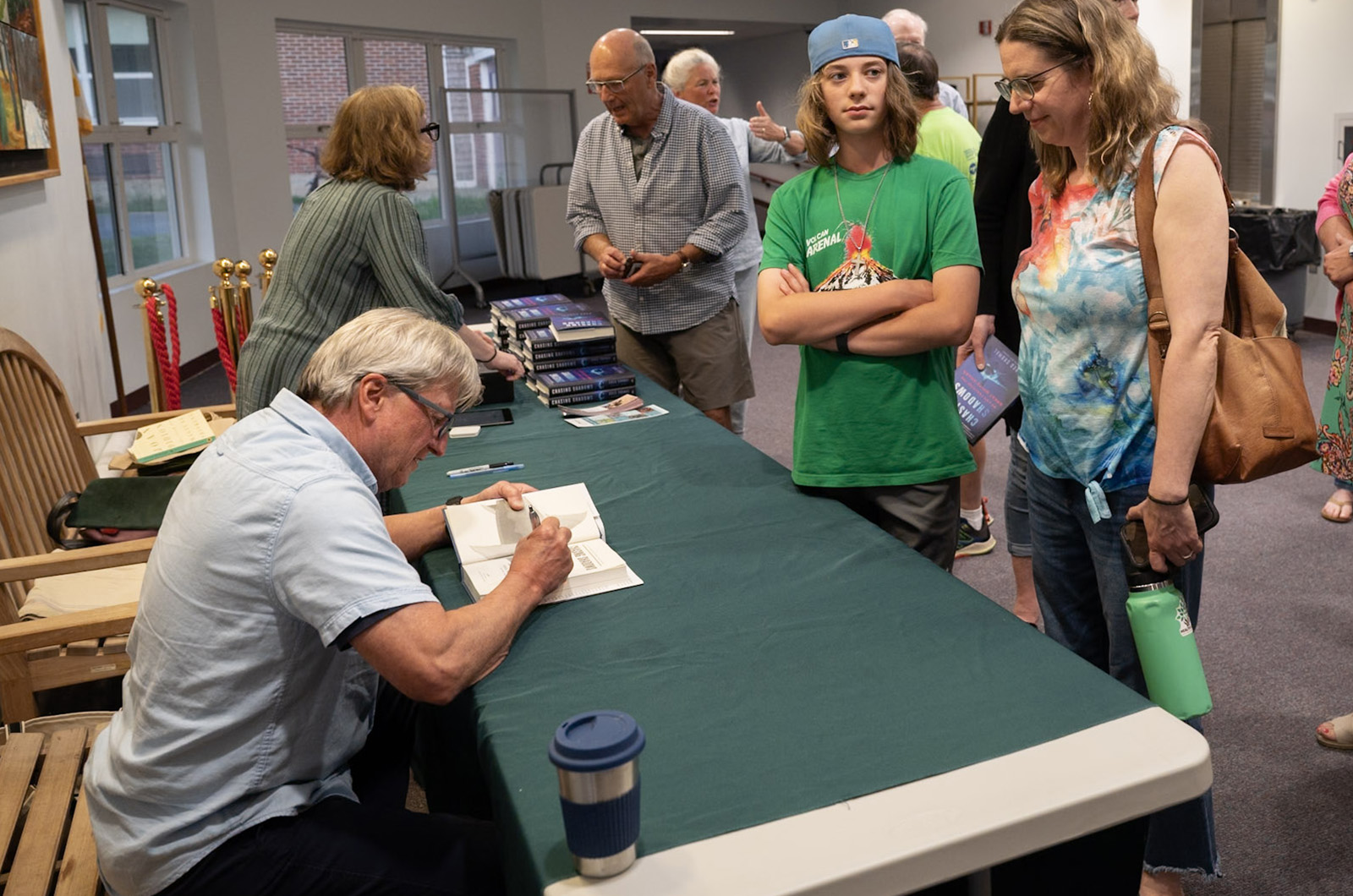

On Monday night, he returned to the Performing Arts Center at the regional high school to discuss a career spent pushing the study of sharks into new waters — and to offer a picture of scientists’ best understanding of great white shark behavior on the eastern seaboard.

Mr. Skomal arrived on the Island “sight unseen” in 1987, he said, fresh from a PhD program. He had a handshake deal from the Massachusetts Fisheries that if he agreed to operate its local outpost, they would continue to back his research on sharks.

“There was no better place than Martha’s Vineyard,” Mr. Skomal said.

After all, Jaws, the blockbuster movie that had helped inspire Mr. Skomal’s interest in marine biology, had been filmed on the Island in the 1970s. Mr. Skomal would eventually live just a few steps from Menemsha Harbor, where the famed Orca carried Robert Shaw, Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss in pursuit of the great white shark terrorizing the beaches of Amity Island.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Mr. Skomal’s research focused on the sharks most common in Atlantic waters — blue sharks, brown sharks and even larger makos. The great white shark, like its fictional counterpart in Jaws, was extremely difficult to find.

“They were so elusive, they were not easy for any of us, as scientists or even fishermen, to find,” Mr. Skomal told the crowd at the PAC.

For decades, Mr. Skomal’s mentor Jack Casey had been encouraging fishermen to tag sharks they encountered on the Atlantic coast with a very simple analog tag — essentially an identification number, which could be reported to his team if the shark was ever rediscovered by fishermen or other biologists.

The program ended up tagging 300,000 sharks. Only 56 were white sharks, and only two white sharks were ever rediscovered after their initial tagging.

Another of Mr. Skomal’s mentors, Frank Carey, had speculated in the 1970s that the absence of gray seals from the New England shores had driven the great white shark to other feeding grounds.

In the four decades since, that thesis has borne out, Mr. Skomal said.

Since the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, seals have returned in force to the Outer Cape beaches. White sharks have slowly followed their favorite food source, while also gaining protection of their own after the national fisheries listed white sharks as a protected species in 1997, preventing fishermen from landing the species.

On the one hand, the return of seals and sharks was “a beautiful conservation success story,” Mr. Skomal said. “A perfect restoration of a classic predator-prey relationship, which looks really good on paper.”

But that restoration played out as the area became a more popular tourist destination, drawing thousands of visitors to its oceanside beaches.

“When we bring back the seals, we bring back the white sharks, and we have the potential for human conflict with these animals,” Mr. Skomal said.

The 2010s saw a series of shark attacks across Cape Cod, culminating in 2018 with the first fatal attack confirmed in Massachusetts in 80 years.

But advances in transmitter and tagging technology in recent years could help prevent future attacks as scientist develop a more in-depth picture of shark behavior in the North Atlantic, Mr. Skomal said.

In 1979, Mr. Carey had managed to tag a single great white shark with an acoustic transmitter, collecting three days of unprecedented data on white shark movement and behavior. Today, hundreds of tagged white sharks, swimming through a coastal network of detector buoys, allow scientists to follow the migration and feeding patterns of the sharks at all stages of their life cycle, Mr. Skomal explained.

Research suggests that when the species migrates north in the late summer, juvenile white sharks feed on squid and small fish off the coast of Long Island, while mature sharks push on to hunt the seal populations of Monomoy, the Outer Cape and eastern Nantucket.

In other words, great white sharks tend not to linger in Vineyard waters, Mr. Skomal said.

For decades, Mr. Skomal did most of his work from the back end of a scalpel, relying on dissection to learn about shark life cycles and feeding habits. Today, he’s glad that less invasive methods of tagging and population monitoring, as well as engagement with local fishermen, have allowed shark scientists to push conservation efforts.

“Today we’re looking for patterns in behavior that we can share with the beach managers, lifeguards and the general public as to what, where and when might not be the best time or place to be in the water with these animals there,” he said.

Comments (1)

Comments

Comment policy »