In his basement office, Chilmark resident Edward Grazda has stacks of boxes labeled by the places he’s photographed over an acclaimed career behind the lens of a Leica. Afghanistan. Peru. The American Southwest. Pakistan, New York city, Mexico.

A couple of rooms away is his darkroom, reassuringly stocked with the basic technology of black and white photography, some of which dates back to the days when he was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

During his long career, Mr. Grazda has published 11 books of photography, and his pictures are in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The New York Museum of Modern Art, The New York Public Library, and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

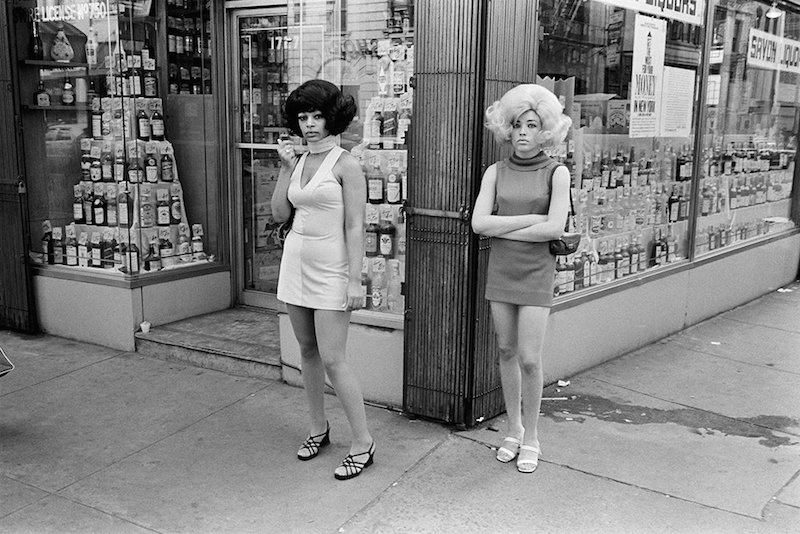

He has photographed subjects as widely varied as musicians, mosques, homeless people and an old trading post. Recently, at the Pathways gathering space, Mr. Grazda talked about his latest book, Mean Streets, New York City, 1970-1985, published in October. Mean Streets documents a different time in America’s largest city, a time when crime was higher, the streets were coarser and there were parts of Manhattan that scared tourists away instead of drawing them in.

It was also a place where rents were cheap, the streets were less crowded with the fashionably rich, and hopeful young artists could create careers for themselves. Mean Streets is an unvarnished look at the New York city Mr. Grazda called home during the 1970s and 80s.

Throughout his career, he has carefully catalogued and filed his contact sheets and negatives, so he can quickly find nearly every photograph he has ever taken. Two years ago, he began going over some of the pictures he took on the streets of New York, between various trips to South Asia and Latin America. They were everyday pictures from everyday life.

“I didn’t have a concept of what the book necessarily would be, or the title, or even the theme,” said Mr. Grazda. “I was just picking out the pictures that I kind of liked.”

One shows a grizzled New Yorker hunched over a mailbox. Another shows an old television set on fire. Another documents street preachers common in the era. Each picture is an unposed slice of life in a time and a place that no longer exists.

“In the early seventies when I first came to New York, I had a Leica,” he said. “The scene was if you were a photographer you were carrying your camera around all the time. Even though you were going to work at an office, you would have your camera with you. At night you’re going out, you always had your camera with you. That’s what you did.”

He said it is difficult to describe his street photography, but it is heavily influenced by photographers he likes and studies, including the Depression-era photographer Walker Evans, and more contemporary artists Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand.

“It’s basically just photographing anonymously on the street,” he said. “Looking at the world that’s there, without any agenda. It’s just something you see. What makes you pull a camera out is probably my awareness of photography history, the knowledge of what other photographers have done. The best photography school is looking at lots of photography books. By doing that you get a sense of what might be good, but it’s very intuitive. When you’re taking those pictures it’s 1/250th of a second. It’s in you. You’ve grown up looking at these pictures and these are the photographers you like. You’re not trying to necessarily copy them, but somehow you’re following in that path.”

While not one to lament progress, Mr. Grazda does seem wistful for the days when New York city was a meaner, but perhaps less complicated, less pretentious place. He often worked as a carpenter’s assistant or a photographer’s assistant to make ends meet. Later he taught his craft to students at The International Center for Photography.

“I’d work for some months in New York, try to get some money together, make a trip to Mexico or somewhere,” said Mr. Grazda. “Rent was cheap in those days, you could afford to do that. You can’t do that anymore. It was very conducive to this kind of lifestyle. So I was lucky. When I graduated from RISD in 1969, money had nothing to do with art. There was no concept of making a portfolio, here’s your resume, you’re going to have a gallery show. Didn’t exist. I find it sad.”

Mr. Grazda remains devoted to film, and black and white photography, in a world that has almost completely changed to digital and color.

“Black and white was cheap, you can control it, and I like black and white,” He said. “Color I’ve always found a little bit garish.”

On his trips abroad, he would often shoot 100 rolls of film, and not see what he had until he got home to develop the film later.

“Unlike digital, you don’t see any of the pictures. You have to be self-confident enough to think, well, I’m doing okay. The nice thing is you come back, and then you relive that trip by developing all the pictures. When you’re there taking the pictures it’s a totally different experience than actually looking at the pictures. Those two realities come together, what you experienced, and what it really looked like.”

Though there have been many advances in photographic technology over his lifetime, Mr. Grazda still trusts his Leica and just two lenses to capture his subjects in sharp moments of reality.

“The advantage of the Leica is it’s very small,” said Mr. Grazda. “People wouldn’t notice it. The quality of the lenses are the best you can get. It’s really small, it’s really fast, you can put it in your pocket, and it’s strong. If you’re traveling in third world countries, you want to be discreet. All my photography has been discreet, without lights, and a lot of things like that.”

Since he moved to Martha’s Vineyard full time in 2006, Mr. Grazda has occasionally turned his camera on the Island’s people and places.

“I have a little bit,” he said. “I carry the camera around, I go to different things, I’ll take a picture here and there. I’m working on one project, a church in Aquinnah. It is a different environment. I like it a lot, but nature is not the kind of photography which I always did. You take the pictures now, just like I took the pictures in the 1970s, you don’t know what’s going to happen. I’m taking pictures of trees and nature and sheep out here. In five years they might end up having some meaning.”

Comments (5)

Comments

Comment policy »