Inside of a shipping container studio on Chappaquiddick, artist Zach Pinerio stands surrounded by shelves of bowl blanks, a wall full of sharp tools and a floor coated in wood shavings. He’s wearing rolled up jeans, tortoise-shell glasses and a dirty white T-shirt that’s nearly the same light shade of brown as the bowls.

He says he gets into the studio at about one in the afternoon and works until late at night, losing track of time as he falls into the hypnotic rhythm of his work.

“It’s part of what keeps me sane. I don’t have anybody in my face,” he says with a laugh.

Mr. Pinerio pulls out a bowl blank that on first glance appears indistinguishable from hundreds of others.

“This is a sycamore maple from North Water street, at least 60-years-old,” he says. He continues to point out bowls milled from a Norway maple in Edgartown and an American chestnut from West Tisbury.

Mr. Pinerio says he hauled the wood over to Chappaquiddick in the winter, saving them from being thrown into a wood chipper or burned, a fate he said befalls too many of the Island’s rich and diverse population of trees.

“I like to think of them as the trees that got away,” he says. “That’s what keeps me up [at night] a little bit.”

He prides himself on using every part of the tree and that all the wood he uses comes from the Vineyard.

“It all has a story behind it. I enjoy making stuff for people they’re going to tell a story about.”

After collecting the wood, Mr. Pinerio takes it to a sawmill next to his property to cut each log into two bowl blanks. Then, through a four-month process he calls “intentionally slow” he begins to shape and dry the raw bowl material into a finished product.

The bowl blanks are chipped and edged on the sides of the bark, called “live edges,” and at this point have an irregular oval shape. He secures the sycamore maple bowl into a metal form on his wood lathe, an apparatus used for turning the wood at up to 3,500 rotations per minute, and straps on his tool belt and a face shield. Then he grabs a gouge, a long knife used for chiseling and “curing” the wood, from the wall and fires up the machine.

As soon as the gouge cuts into the bowl exterior, the shavings start to fly like Silly String and pile up on Mr. Pinerio’s flip-flops. The low hum of the machine provides a bassline for a staccato symphony of sound as the bowl begins to take form, smooth and consistent along the sides.

“You can hear when it’s not going well,” he says after using a vacuum attached to his belt to blow the shavings off his feet.

“You can also feel it when it’s getting round,” he adds. “It starts to cut like butter.”

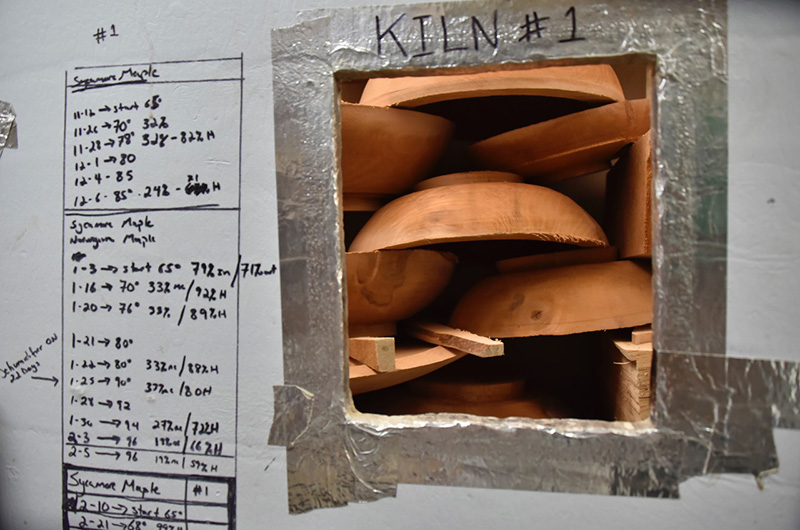

Once the roughing is complete, the bowls are given a sauna treatment inside two kilns heated up to 95 degrees. Mr. Pinerio explains that the wood starts with 35 to 40 per cent moisture content, but needs to be dried down closer to 10 per cent to ensure the bowls can be used long-term.

“The bowls will eventually warp and crack without drying,” he says.

After about a month in the kiln, the bowls are ready for a last touch-up of walnut oil to seal and protect the wood. He sells the bowls at the Vineyard Artisan Festival in West Tisbury, and at various stores around the Island.

Included with each purchase is a card that teaches owners how to properly care for the bowl and explains where the wood came from.

“There’s something cool about using a bowl made from a tree in your backyard,” he says. “The fun is figuring out where it’s from and who it’s important to.”

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »