Chef Deon Thomas used to bring the conchs with him from Anguilla. For years he spent winters on that island, and before returning to the Vineyard he and his assistant chefs would load 100 pounds or more of the Caribbean conchs, frozen, into their suitcases for the flight to Boston.

In Anguilla and in Mr. Thomas’s island of origin, Jamaica, the conchmen stay out at sea for up to a month, returning with hundreds of queen conchs bound together with rope. They store them in the water beneath their docked boats.

“Each conch is a dive in 20 feet or more of water,” Mr. Thomas said on a recent morning, sitting in his restaurant at the VFW in Oak Bluffs, drinking coffee as cooks arrived for the workday. He took a queen conch shell from the shelf, too big to fit in one hand. In the old days, he served the Caribbean conchs at his Corner Way restaurant in Chilmark — fried, grilled, in stew, chowder and raw in salad.

When it became illegal to transport more than 10 pounds conch from the Caribbean, he was forced to find an alternative to keep up with demand on the Vineyard for the delicacy. He turned to the much smaller conchs, whelks really, caught daily in the waters around Martha’s Vineyard.

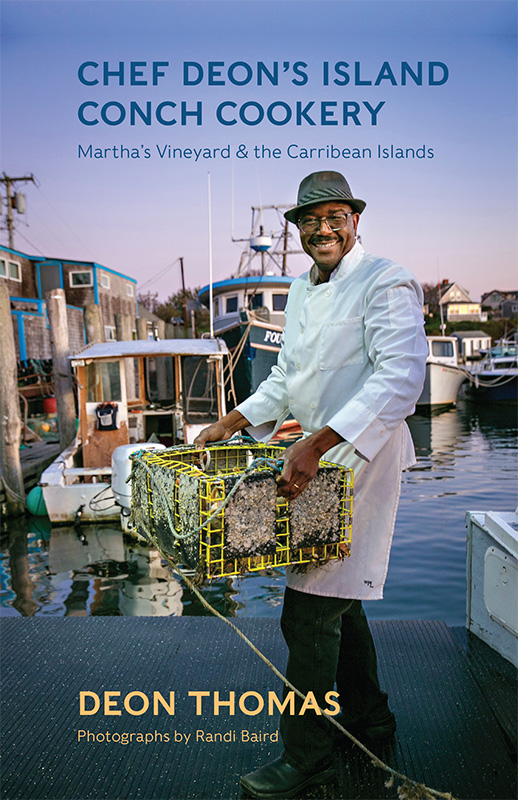

His new cookbook, Chef Deon’s Island Conch Cookery, chronicles the results, with dozens of recipes for the humble northern sea snail and stories about Mr. Thomas’s many islands of origin alongside richly detailed images by photographer Randi Baird. The cookbook was edited by Island writer and poet Emma Young.

To the uninitiated, the shellfish dilettantes, the whelk and the conch may seem similar, but they are very different according to Mr. Thomas. The whelk’s diet, for one, is unlike that of the Caribbean queen conch, which feeds mostly on algae and other tiny plants.

“These guys are ravenous carnivores,” Mr. Thomas said, holding the barnacled shell of a local whelk. “They eat the mussels and the oysters. That’s why the fishermen hated them.”

An early hurdle was learning to efficiently extract the animal from its spiral shell. In Anguilla, Mr. Thomas would hook the meat and hang the animal from a tree. Over the next hours, the weight of the shell would become too great for the sea snail’s strength, and it would slide off and drop to the ground, leaving the meat hanging. Mr. Thomas discovered that whelk shells weren’t heavy enough for that strategy.

First, he tried crushing the shells to extract the meat, but the shards and splinters were sharp and dangerous. To leave the shell intact he froze the animal for 48 hours, then thawed it and pulled the meat slowly out. The temptation was to unfurl the snail away from the shell-like measuring tape, but Mr. Thomas has learned to ease it out along the outer wall, continuing the spiral the animal has grown to fit.

“You just have to get intimate with the conch,” Mr. Thomas said of the process. “It was hard at first but I persisted.”

He brings the same patient intimacy to his cookbook, with its photographs from the Bahamas and from Menemsha, its stories from Mr. Thomas’s childhood, and thoughtful meditations on the anatomy and science of the animals. In a recipe for Conky Dumplings, for example, Mr. Thomas recalls buying the street food from vendors in Anguilla.

“The ground and chopped conch is cooked in brown butter and sesame oil... During schooldays at the farmers’ market, I had to contend with the minions on their lunch break, tourists and others to get a portion,” he writes.

His goal, he says, is to create a conch revolution on the Vineyard. The animal’s abundance and accessibility make it a sustainable option for the Island diet, an untapped resource Mr. Thomas plans to continue to explore with his particular reverence.

Mr. Thomas took some shells with him to the beach to make a mosaic one afternoon months ago for Ms. Baird to take photographs for the cookbook. He arranged them carefully, shell by shell, in the sand.

“And then the surf came,” he said, laughing. The waves quickly ruined his work, but Mr. Thomas was unperturbed.

“Sometime when you’re walking the beach you’ll find a conch shell and it’s broken, but you can see the spiral. That was my thought. In decades to come, someone will find these shells. The sand will break them up and someone will be walking the beach and think well, what is this?”

Chef Deon’s cookbook can be purchased at the VFW in Oak Bluffs.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »