Many splendid homes on Martha’s Vineyard were built by whaling captains, but little has been written about the origin of the money that allowed their construction.

For 156 years — from 1738 to 1894 — whaling dominated the economy on Martha’s Vineyard.

Southern New England was known for the oil derived from the capture of whales. In the early years the oil from sperm whales was used to produce smokeless candles for wealthier Americans. Over time the oil lit streets and lubricated the American Industrial Revolution. In later whaling years, the baleen from whales was used like plastic and spring steel to manufacture a host of products. Ambergris, a byproduct of sperm whales, was an extremely valuable component in making perfume, although it was later outlawed. One Edgartown whaleship, the Mary Frazier, returned from a whaling expedition in 1883 with a 25-pound piece of baleen that alone may have been worth as much as $500 per pound — in today’s dollars that would translate to $300,000.

The earliest recorded whale trip left Martha’s Vineyard in 1738. The last was the Hattie E. Smith’s trip that ended on Nov. 18, 1894, captained by John E. Johnson.

Whaling spanned three wars: the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

Benjamin Franklin, the U.S. envoy in London, was once queried by the British on how ships crossed the Atlantic so quickly. Franklin consulted a relative who was a whaling captain and learned that the Gulf Stream, unknown at the time to the Brits with its three-mile-per-hour north or southbound current, could make a two to three-week difference in the trip.

Meanwhile, the British used their sea power to blockade our trade — including whaling — and damage our whale oil-fueled economy. They captured or killed 1,200 seamen and took 134 of our ships, many of them whalers. Impressment affected our national economy so deeply that in 1796 the Fourth Congress authorized Seaman’s Protection Certificates, which served as passports for U.S. seamen. For black seamen, the certificates were also proof that they were free men and not slaves.

Men of color were full participants in the whaling industry, a business so difficult and dangerous that most people only went out once. In an era when there were few options for advancement among men of color on land, at sea the experience they gained from whaling made promotion achievable. Captains who managed to return home safely with crew and cargo were captains above all else — few cared about the color of their skin.

Five men of color either led whaling voyages from Martha’s Vineyard or were based on the Island. Three of them — Capt. William A. Martin (black), Capt. Jasper Manuel Ears (mixed blood) and Capt. John T. Gonsalves (Cape Verdean) — returned in the late 1800s with oil valued at more than $766,000 in today’s dollars. Amos Jeffers, a Native American from Aquinnah, was lost at sea in a fishing accident before he would have captained the Mary on a trip from New Bedford, according to an account in the Gazette published in July 1847.

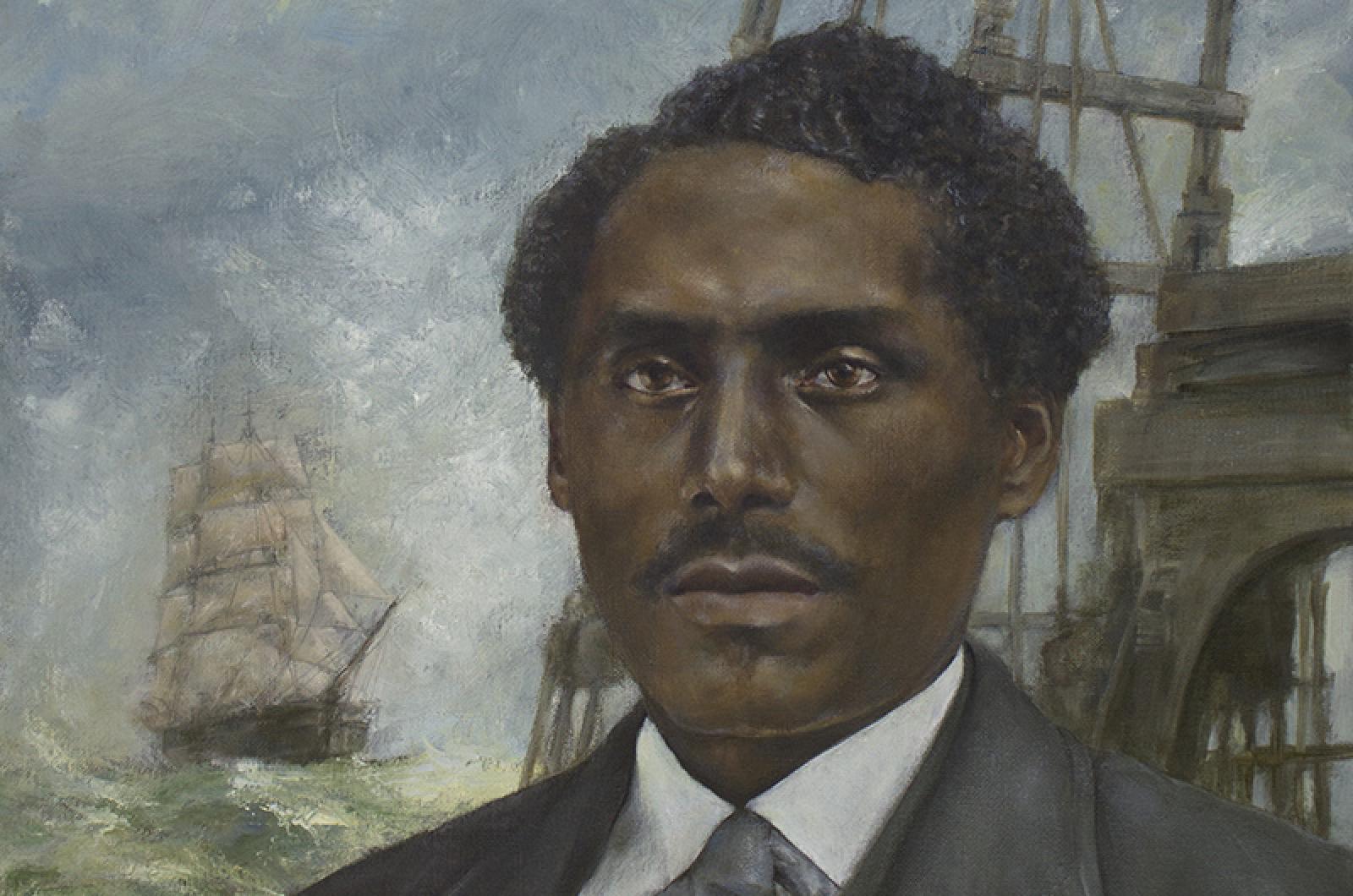

Joseph G. Belain (pictured here) was born on Martha’s Vineyard to an extensive whaling family and went out on 22 whale trips, two as captain of the Eliza and the Navarch. A mulatto, Belain was the last living captain with Native American ancestry. His obituary in the Oct. 22, 1926 Gazette carried the headline: Pigeon from Sea Alights on Hearse, and acknowledged Belain as a Champion of Gay Head Whalers.

Learning from our native population how to capture whales, Vineyard men were renowned, not only from the pages of Moby Dick but in whaling ports worldwide. The American whaling industry lasted from 1715 to 1928, a 213-year period during which over 2,700 ships conducted 15,913 whaling trips. Martha’s Vineyard’s whaling captains and crewmen were prized worldwide and sailed from virtually every port used for whaling.

Numbers help tell the economic story. There were 175 whale captains who sailed 98 ships on 247 voyages from Martha’s Vineyard and returned with whale products valued at more than $228 million. That doesn’t include the proceeds from voyages led by these Vineyard captains from Nantucket, New Bedford and the other 70 some whaling ports. Even today, $228 million could account for the construction of many beautiful homes. •

The top 10 Vineyard whaleships follow:

1. Vineyard, 11 trips, total value $25,031,056, sailed from 1832 to 1871.

2. Almira, 14 trips, total value $24,086,436, sailed from 1822 to 1868.

3. Champion, 11 trips, total value $20,621,092, sailed from 1833 to 1869.

4. Splendid, nine trips, total value $16,604,292, sailed from 1839 to 1872.

5. Mary, nine trips, total value $ 13,399,055, sailed from 1836 to 1871.

6. Europa, four trips, total value $12,744,131, sailed from 1853 to 1872.

7. Ocmulgee, six trips, total value $10,225, 354, sailed from 1844 to 1862.

8. Pocahontas, six trips, total value $8,438,009, sailed from 1838 to 1857.

9. Loan, eight trips, total value $7,393,050, sailed from 1818 to 1841.

10. Delphos, six trips, total value $6,281,595, sailed from 1835 to 1846.

All told, these ships brought in $134.6 million from 1818 to 1872.

Skip Finley, former Gazette town columnist for Oak Bluffs, recently completed his first nonfiction book tentatively titled Whaling Captains of Color — America’s First Meritocracy, to be published by the Naval Institute Press.

Comments (6)

Comments

Comment policy »