Sigrid Nunez, author of The Friend, did not expect her seventh novel to have as its protagonist a writer living in New York.

“This is frowned upon,” she said. “Boy, would I not have written this book if I had thought in the very beginning that it was going to be a book about a writer.”

But the way Ms. Nunez talks about writing, it’s as though she had no choice in the matter, like writing The Friend was an experience of discovering her central character rather than creating her. Ms. Nunez said she does not make an outline. Rather she begins on page one and slowly and methodically, over the course of a couple of years of daily progress, works her way to the end.

“The way she observed things, the way she thought about things, the way she read books, the way she culled things from books, only a writer would do that,” Ms. Nunez said of her protagonist. “So I really was stuck. I was stuck with her being a writer, and so I made the best of it.”

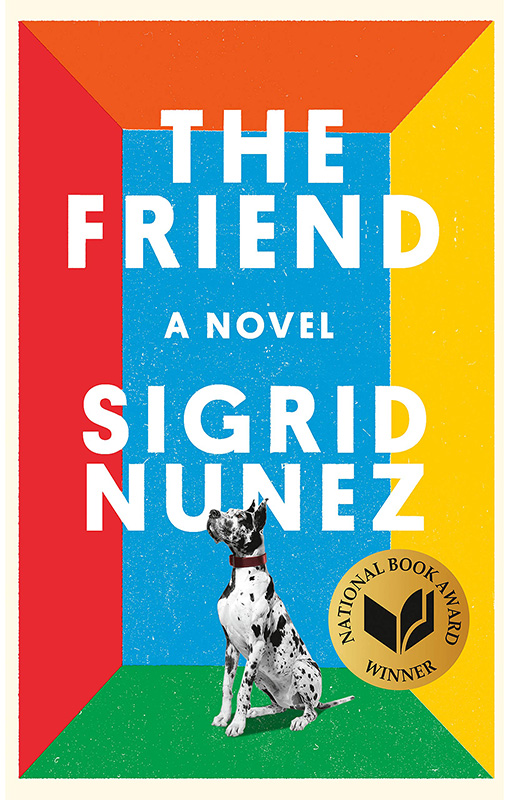

In The Friend, which was published last year and was honored with the National Book Award, a middle-aged woman wades through debilitating grief after the suicide of her longtime friend and mentor (also a writer). She inherits the dead man’s massive Great Dane named Apollo, who is also in the throes of grief, and the animal takes over her life as well as her tiny, rent-controlled Manhattan apartment where his presence is explicitly prohibited.

The book follows a thread through the woman’s loosely associated observations, memories and questions. The character often cites the work and advice of other writers, including from Natalia Ginzburg: “You cannot hope to console yourself for your grief by writing.”

She does not take that advice. In fact, writing and grieving for her seem to become indistinguishable. Skating around the edge of an emotional breakdown, the woman constantly observes and collects: a homeless person’s handmade sign, the meaning of a pop-up advertisement on her computer, an overheard confrontation in the post office, Apollo’s every move and glance.

As she and the dog become inseparable, she acknowledges her audience: “There’s a certain kind of person who, having read this far, is anxiously wondering: Does something bad happen to the dog?”

It is a repeated question.

Recounting her experiences, the narrator contemplates the act of turning what is real and lived into something written on the page. She notices her writing students tend to assume that all writing is based on life, that all characters are based on real people. She brings up the question of whether it is morally acceptable to use real people in fiction or whether doing so infringes on people’s right to ownership of their own stories. If they do spend their lives preying on real people, are writers just vampires?

Ms. Nunez said no one she knows will recognize themselves in her work. She has not used real people since her first book, which was about her parents.

“I felt that was material that I had to write about in order to move on myself,” she said.

The subject of the protagonist’s grief in The Friend is the kind of man who has come under some scrutiny in recent years: the professor who sleeps with his students, who sees teaching as a form of seduction, whose marriages end in betrayal. Theirs was not on the whole a romantic relationship, but the narrator watched closely as he progressed through three wives and countless affairs and listened as he bemoaned the changing culture of academia. She remembers how he was wounded when he was confronted by a group of female students who collectively demanded that he stop calling them “dear.”

Ms. Nunez said she came up in an era when a male professor could get away with having male students submit writing samples to gain admission to a class, for example, while female students had to sit for an interview so their appearance could be assessed.

“The way men of that time behaved is if they had the opportunity, they took it. And that’s changing,” Ms. Nunez said.

But, unlike many contemporary works that take on similar subjects, The Friend does not condemn the mentor or issue a verdict. Instead, it is a finely wrought study of how it feels to lose someone very dear while being deeply and intimately aware of their flaws.

Ms. Nunez said she has received a great deal of correspondence from people who tell her the book aided them in their own healing processes. It was not an outcome she anticipated.

“It has actually turned into a book that has spoken to people about grief and loss and suicide loss and has been consoling, so that’s been a very good thing for me,” she said.

Though her sadness becomes at times insurmountable, the writer in the book continues to write. Word by word and thought by thought she finds her way through the grief.

“In some ways it was very difficult. In other ways it felt very consoling,” Ms. Nunez said of writing the book. “Much of the time it really just felt like work. You know, how can I get the right sentences in the right order on the page to tell the story that I’m trying to tell?”

The page before the final chapter of the book, the chapter where we finally find out whether something does happen to the dog, bears a single sentence: DEFEAT THE BLANK PAGE!

On Saturday, August 3 at 10 a.m., Sigrid Nunez will take part in a panel called Fiction: Transformative Friendships. On Sunday, August 4 at 12:20 p.m., she will participate in a discussion with Elizabeth Benedict.

Comments

Comment policy »