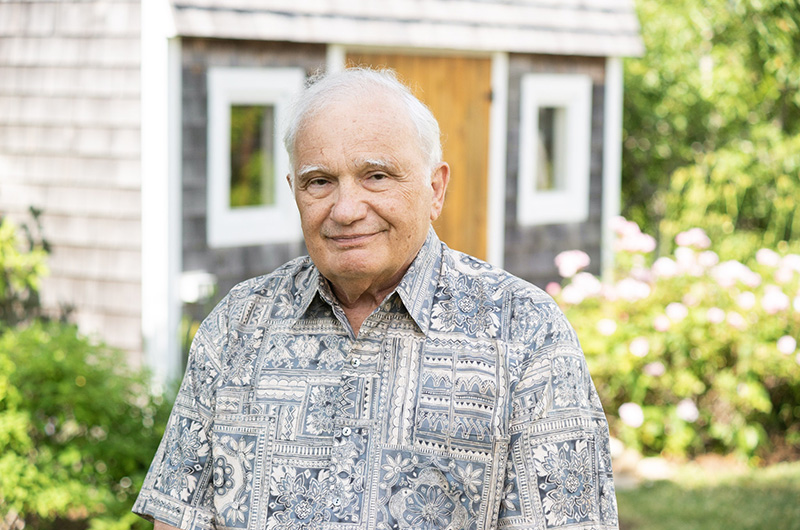

Nicholas Basbanes began his career as an investigative journalist, working at the Evening Gazette in Worcester. Later he became the book editor of the Worcester Sunday Telegram, interviewing more than a thousand authors during his tenure there. One of them was David McCullough, who suggested to the young journalist that he consider writing books, in particular focusing on the biographical form.

Mr. Basbanes took this suggestion to heart.

This June, over 40 years later, he published his 10th book, a definitive study of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called Cross of Snow. The book has received rave reviews from the New York Times Sunday Book Review and the New Yorker, and topped the charts on the Wall St. Journal’s summer reading special.

Mr. Basbanes began his journey with Longfellow in 2007, with an article he wrote for Smithsonian Magazine celebrating the poet’s 200th birthday. While researching the piece, he found himself drawn to the poet and his complicated literary legacy.

A seasonal resident of Oak Bluffs, Mr. Basbanes said during an interview with the Gazette that Longfellow was the most celebrated American poet and public figure of the 19th century, but had been long-since been dismissed by the literary community — his work excised from anthologies and his poems removed from curricula. Only recently have academics begun to re-examine the poet and his legacy.

It is this dismissal that Mr. Basbanes interrogates head-on in his biography. The book, titled after a mournful sonnet Longfellow composed in honor of his wife’s death, aims to reintroduce the poet to the American public.

According to Mr. Basbanes, Longfellow has many lessons to teach contemporary readers. Citing his proficiency in an impressive number of languages and his work translating canonical European writers into English, Mr. Basbanes bills Longfellow as a polymath and a cultural ambassador of sorts.

“He really can be argued as being at the forefront of multiculturalism in the United States,” he said. “He was one of our very first multiculturalists before there was even a phrase to describe that.”

The author’s affection for his subject is palpable. When he speaks about Longfellow, he does so with genuine passion, the way one might describe a dear friend.

“Name me an American poet who writes a better sonnet than Longfellow—they’re exquisite” he said. “If you don’t like him, you don’t like him, but he’s too good to be to be disposable.”

The book also focuses on Longfellow’s second wife, Fanny Appleton, and her impact on his work. According to Mr. Basbanes, telling Fanny’s story was essential to the narrative.

“I’d like to think of this as a dual biography of the two of them,” he said. “She was brilliant woman and a true intellectual partner . . . . That story really hadn’t been told.”

Mr. Basbanes spent eight years doing research, drawing from countless documents while he wrote, diving into both Longfellow’s and Fanny’s abundant journals, travel entries and correspondences. He said the skills he acquired as an investigative reporter have served him well.

The research also brought Mr. Basbanes across the Northeast to historic sites in Longfellow’s life, including his hometown of Portland, Me., the Bowdoin College Library where Longfellow studied, and the Longfellow Literary House in Cambridge. The literary house marked a key point in Mr. Basbanes’ journey with Longfellow. “[The house] is unique because not only is it the home of a notable writer, but everything in there is authentic and original to the owners,” said Mr. Basbanes. “It was amazing, the opportunity not only to use archival materials, but material objects. The objects really can be used productively to help you tell a better story.”

The publication this summer of Cross of Snow coincides with the 25th anniversary of his first book, A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books., a perfect beginning for a life spent working with words. Mr. Basbanes is already pondering his next book, another biography of a 19th-century figure.

“I’m 77 and I ain’t done,” he said with a laugh.

Comments (3)

Comments

Comment policy »